To fill the hour - that is happiness, to fill the hour and leave no crevice for a repentance or an approval.

-Emerson

Following on from last week, the Dalai Lama’s prescription for a long and happy life is one word: routine. He practices what he preaches, from getting up every day at 3.30 a.m. to meditate to going to bed at 8.30 p.m. (as told to Pico Iyer). This, mind you, is for a guy whose life could probably use a spot of routine: at two years old, he was chosen/identified as the reincarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama; soon after he was taken from his remote village in Tibet near the Chinese border to the capital, Lhasa, for years of intense education; at 15 he was formally enthroned as the 14th Dalai Lama; then after unsuccessfully trying to navigate politically between the Chinese government and the CIA, escaped to India at age 24, where he set up “Little Lhasa” in Dharamshala for his thousands of followers. He’s been actively involved in trying to gain autonomy for Tibet ever since. Yeah, I can see where, at age 82, he’d appreciate a life free of sturm und drang. Read Heinrich Harrer’s Seven Years in Tibet for a European’s take on his early life.

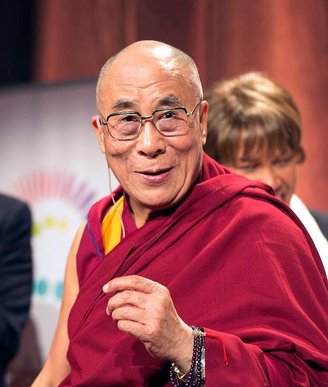

The 14th Dalai Lama in 2012 (*christopher* via Flickr, Creative Commons)

(Before taking issue with the old boy’s prescription, I just want to clarify something about age statistics. I said we were living longer than ever before — meaning, of course, on average. For instance, American men born in 1907 could expect to live to 45.6 years, while in 2007, their life expectancy at birth was 75. Going back farther — judging as best we can from dates on tombstones — roughly half of Romans who survived to 15 were dead by 45. But that’s not to say that our maximum age has increased much. Rameses II made it to his 90s, the Greek rhetorician Isocrates died at 98. He probably would have lived longer; according to legend, he starved himself to death after his erstwhile hero, Philip II of Macedonia — Alexander’s dad—defeated a coalition of Greek poleis. We don’t do much better today for maximum age: in 2014, 72,000 Americans, out of a population of 319 million, were over 100, just 0.02 percent.)

Okay, so the Dalai Lama says “routine” is the key to longevity. But, as I discussed last week, the number of years doesn’t count much if, for instance, you’re miserably lying in a hospital bed for decades. Surely you have to factor in quality of life — I suggested we measure quears (as in a combination of quality and years) to rate our lives. And for me — perhaps for you, I’d be interested in hearing—quality requires novelty. Not all the time—a life just filled with new experiences, day after day, would quickly pall — but fresh enough to keep our busy minds satisfied and limber with new places, new people, new happenings, new challenges. “Routine,” after all, can mush into rote, rote becoming habituation, thence mindlessness. (Think of an unvarying commute, or — for those of us brought up to it — daily recital of the Lord’s Prayer.)

How to combine the two — novelty and routine — is hard enough to figure out at any one time, let alone to plan for the future, it’s too much of a moving target. But if I were forced to choose one, I’d go with novelty. For which I blame my early encounter with Autumn Journal by Irish poet Louis McNeice:

CLICK TO MANAGE