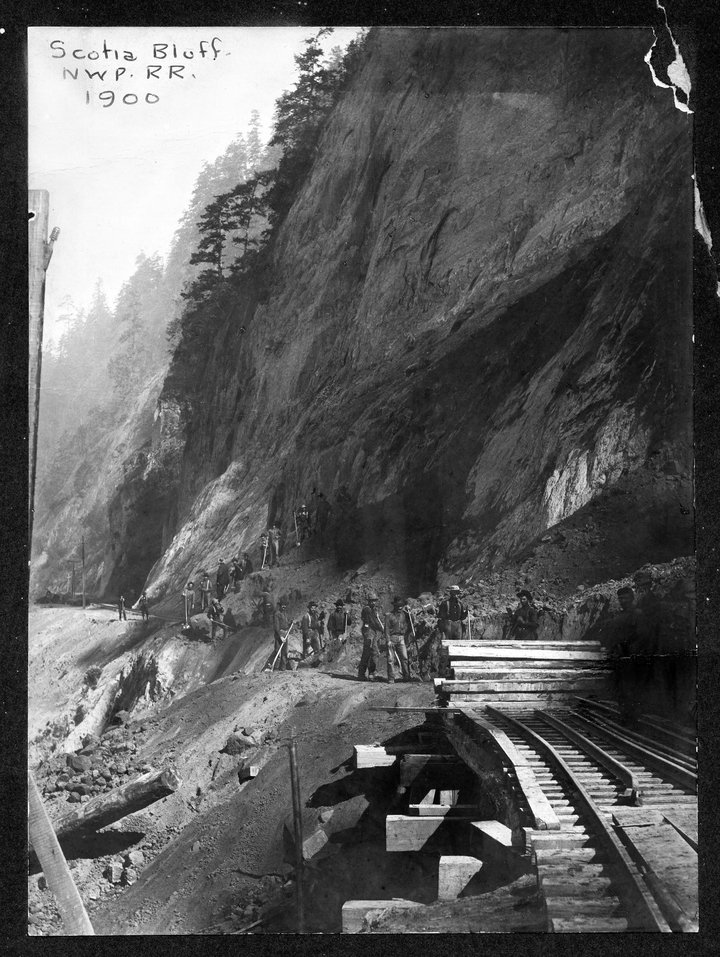

The Northwestern Pacific line was built underneath the perilous Scotia Bluffs. The choice was just one of the poor decisions that doomed the railroad forever. Photo: Josh Buck.

From the moment in 1907 that the the prospective route through the Eel River Canyon was finalized, the Northwestern Pacific Railroad (NWP) was doomed.

The initial problems were with the railroad’s design, location, fixed route and ownership — questions of a generally operational and logistical nature. Later, the line’s problems were a bit more existential. They became about financially surviving the onslaught of natural disasters in the face of a collapsing timber market, and about competition from the trucking industry on the mostly parallel Highway 101. This came to a close with the economic collapse that permanently shut down the railroad in 1998.

Redwood lumber, lumber mills and locals throughout Humboldt County prompted many companies to construct railroads. Some of the predecessor railroads that existed prior to 1907 in Humboldt County ultimately shaped the railroad’s north end route between Eureka and Willits. The first of these predecessors was the Union Plank Walk Company (later known as the Arcata and Mad River Railroad), which was incorporated on Dec. 15, 1854. It would set the stage for an explosion of railroad growth throughout Humboldt County.

The Pacific Lumber Company’s small logging road, which was built in 1885, was structured along a geologic anomaly known as the Scotia Bluffs — the same route that would later plague the NWP’s right-of-way with constant maintenance and disaster.

###

The wrong place to put a railroad.

In 1863, the founders of The Pacific Lumber Company (TPLC, later PALCO) embarked on a business venture that would ultimately shape the Northwestern Pacific Railroad’s future.

The company purchased six thousand acres of timberland lying along the banks of the Eel River in Humboldt County.1 The question for the TPLC became how to construct a right-of-way from its lumber mill in Forestville north to Fields Landing (south of present-day Eureka), so that lumber schooners would have access to the redwood timber, which they would then ship south.

The TPLC’s first step to building its railroad was to identify an ideal right-of-way out of Forestville. They identified the Scotia Bluffs as the ideal route. This was the first mistake of many that would ultimately set the stage for the NWP’s failure later in 1998.

The railroad was constructed and reached north to Fields Landing. It also connected with the existing Eel River and Eureka railroad, which ran north to Alton.2 Over the course of the first year of operation, though, TPLC was quick to discover that their right-of-way had steadily grown into a problem.

The Bluffs are composed of blue sandstone and layers upon layers of clams, which reveal that sandy beaches and mudflats were once prominent where the Eel River’s water steadily flows to the Pacific.3 To this day, if you hike to the Bluffs via the crumbling NWP right-of-way you’ll find seashells embedded in the sand of the Bluffs in mass quantities. It is for this reason that the route proved to be entirely unreliable, as regular slides over the right-of-way forced TPLC crews to monitor the Bluffs with an ever-watchful eye.

After extensive storm damage in 1886, one resident of Rio Dell detailed the state of the railroad:

TPLC are carrying on operations in an extensive manner. The railroad has been refitted and placed in first-class order and work on their mill is being pushed ahead … they have arranged for the building of a large wharf at Fields Landing, and the piles are now being taken out. It will not be many months before they will be shipping large quantities of redwood lumber to the S.F. and foreign markets.4

This detailed account made by a then-resident was optimistic at best. The entire basis for their projection hinged on the hope that the Bluffs would stand strong and not continue to cause extensive damage and delays. This would simply not be the reality moving forward.

A typical slide is cleared at the Scotia Bluffs by PLC employees in 1900, note that they had use shovels to clear the massive amounts of debris which bombarded their railroad on a regular basis.

One citizen of Rio Dell reported to the local newspaper that “there is an ugly-looking bluff across the river from Rio Dell, and every winter more or less sliding occurs. Since the rains of the last week began, another slide is there. It is predicted that the TPLC will have considerable trouble in the future with that locality.”5

TPLC, having experienced much difficulty with maintenance of their new route, approached the founder of Rio Dell, a man by the name of Lorenzo Painter, with a proposal to construct a new route through his property. The historiography that surrounds Painter is debated, but the general consensus is that he could be described as a man who “loved nothing more than a hard bargain.”6 Painter, who owned much of the flat land in Rio Dell, reportedly refused to allow TPLC to construct a railroad through the town unless TPLC met his steep asking price.

Existing scholarship on the town of Rio Dell written by HSU alumnus James Garrison describes Painter’s asking price as “too high,”7 and TPLC’s management was forced to consider an alternative route. This was the turning point that would set the stage for not only TPLC’s railroad but for all the future administrations that utilized the NWP’s right-of-way on the same route along the Scotia Bluffs. The entire future of Humboldt County’s railroad activity hung in the balance, simply because of one man’s greed.

According to one source, Painter was approached a second time after TPLC had miraculously recovered its right-of-way along the Bluffs. In response, Painter doubled his asking price and was described as “fully confident that they would have to meet his price.”8

TPLC decided to keep their existing route along the Scotia Bluffs, the railroad was never built through Rio Dell and Painter later fell into economic despair. He would eventually commit suicide by jumping off of the Scotia Bluffs trestle and into the Eel River below.9

Despite the consensus of the secondary source material — that Painter asked too much for his land — not all viewed him in this light. On March 26,1898 a Western Watchmen article described Painter as a kind-hearted pioneer who was the victim of false reporting. The article reads:

It has been industriously circulated that it was due to Mr. Painter’s prescriptive policy and exorbitant demands that drove TPL Co. to build the road around the base of the great cliff opposite of Rio Dell. We are told by his old and intimate friends that such is not the case — on the contrary, Mr. Painter offered free right-of-way thru Rio Dell, and only stipulated that the Co. should build a depot at Rio Dell and make it a regular stopping place. This, we are told, is what Mr. Painter maintained until his death.10

The bias of this source is that these were Painter’s friends, who may have wanted him to be remembered not as an egregious landowner but rather as a founding pioneer and caring resident of Rio Dell in its early years. Regardless of which story is true, the die had been cast, and the end result was the same — TPLC’s hand was forced, and they turned to the Bluffs as the long-term solution to their dilemma.

###

Landslides were, and always have been, a regular nuisance for the railroad since TPLC chose to build underneath the Bluffs. The area was a regular problem for Southern Pacific, who would come to own and operate the line in later years. But the maintenance costs were worthwhile to the railroad’s bankers, managers and customers — as well as to those employed to maintain the railroad’s infrastructure — so long as everyone made money hand over fist shipping outbound timber,

When rains start trickling down and under the “itchy old crust”11 of the Scotia Bluffs, the earth can suddenly take the notion that it intends to move, sometimes in rather unbelievable proportions. This very type of disaster occurred on the morning of Nov. 24, 1945.

The inhabitants of Scotia felt the earth shake and they heard a thunderous roar as a massive landslide descended upon the right-of-way from 308 feet above the NWP tracks. It buried 550 feet of the railroad 48 feet deep under dirt, trees and massive stumps. It was noted that the slide was so massive that it nearly “dammed the Eel River.” Initial estimates suggested that the damage would take 30 days to repair, but the NWP and its contractors were able to reopen the railroad in only ten days.12

The chronic landslides, which occurred like clockwork, put railroad employees and passengers at great risk. In January 1953 this type of disaster struck. A massive landslide descended upon the Scotia Bluff tracks and knocked an eighty-ton locomotive off of the rails, into the Eel River below. Three railroad employees within the cab could not escape in time and were killed.13 To this day, a monument honoring the lives of those three men stands in Fortuna as an everlasting reminder of the horrors that engineers and railroad crews had to endure. This was one of the most disastrous events to strike the line, and it left lasting doubts about the safety of the railroad.

But the landslide itself was minuscule in comparison to the landslide of 1983, which closed the railroad for nearly two months. Mudslides occurred regularly during the opening months of 1983 because of torrential rainstorms. One particular slide in late January 1983 at Scotia Bluffs caused hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of damage and shut the railroad down for a month. Two months later, an even bigger mudslide shut it down again.

Although the Scotia Bluffs has been cited as the main trouble spot of the NWP, it was far from the only one. Up and down the Canyon, many mileposts were home to new shifting and sliding areas of the topography that (if left unattended) would render the tracks impassable in given time.

###

Next time: The surprisingly flammable tunnels of the Eel River Canyon. Though everyone knows that earth and water blew out the railroad countless times during its decades-long history, fire also took its toll.

###

Josh Buck is a history major at Humboldt State University. His thesis-in-progress, excerpted here, is a history of the Northwestern Pacific Railroad and the predecessor railroads of Humboldt County. If you’d like to see more photographs and history pertaining to North Coast railroads, please check out the Facebook page “North Coast Railroad History,” which is run by Buck, HSU alumnus Sean Mitchell and HSU student James Bradas.

Have you done some scholarship on matters of local interest? Want to share it with a general audience? Write news@lostcoastoutpost.com. We’d love to hear from you.

###

CITATIONS:

- 1. Susie Baker, “Scotia Home of the Pacific Lumber Company,” within Susie Baker Fountain Papers, ed. Humboldt Room Archive, 1st ed. (Arcata, CA: Humboldt State University Library, 1967), 96: 194.

- 2. Lynwood Carranco and Henry Sorensen, Steam in the Redwoods, 151.

- 3. Evelyn McCormick, “Rio Dell March 16, 1957,” within Susie Baker Fountain Papers, ed. Humboldt Room Archive, 1st ed. (Arcata, CA: Humboldt State University Library), 96: 120.

- 4. “Pacific Lumber Co. June 18 1886” within Susie Baker Fountain Papers, ed. Humboldt Room Archive, 1st ed. Vol. 96 (Arcata, CA: Humboldt State University Library, 1967), 96: 243.

- 5. “Times 12 Dec 1886,” within Susie Baker Fountain Papers, ed. Humboldt Room Archive, 1st ed. (Arcata, CA: Humboldt State University Library, 1967), 96: 95.

- 6. Fred Cook, “Alonzo Painter: A Bad Loser” within History of Rio Dell and Scotia Bi-Centennial Edition (Pioneer, CA: California Traveler, 1980), 47.

- 7. James Garrison, Scotia and Rio Dell (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2015), 23.

- 8. Freed Cook, “Alonzo Painter: A Bad Loser,” 47.

- 9. “Oct 8 1892: L.D Painter, an Old Citizen of Rio Dell Committed Suicide Last Saturday Afternoon,” within Susie Baker Fountain Papers, ed. Humboldt Room Archive, 1st ed. (Arcata, CA: Humboldt State University Library, 1967), 96: 118.

- 10. “Western Watchmen March 26 1898” within Susie Baker Fountain Papers, ed. Humboldt Room Archive, 1st ed. (Arcata, CA: Humboldt State University Library, 1967), 96: 105.

- 11. “Restraining a River…Rescuing a Railroad: It’s All Dirt to Em-Kayans,” The Em-Kayan, February, 1946, 4.

- 12. “Restraining a River…Rescuing a Railroad,” The Em-Kayan, 4.

- 13. “Tragedy Strikes the Scotia Bluffs,” Humboldt Standard, 20 January, 1953.

CLICK TO MANAGE