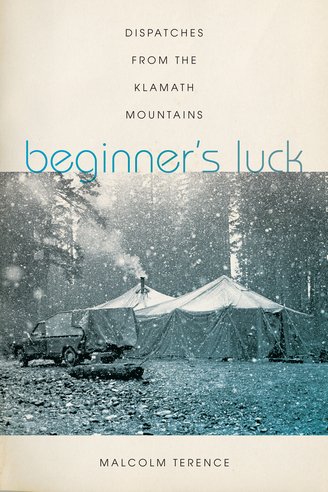

Ed. note: The following is an excerpt from Beginner’s Luck: Dispatches From the Klamath Mountains, a new book by longtime Salmon River watershed resident Malcolm Terence. It is reprinted here courtesy of Oregon State University Press.

Beginner’s Luck is the story of the early days of Black Bear Ranch, a legendary Siskiyou County commune, and of the subsequent decades in the mid-Klamath. “The local mining and timber communities had a checkered opinion of their new hippie neighbors, as did the Native tribes, but it was the kind of place where people helped each other out, even if they didn’t always agree,” reads the book’s advance publicity.

Terence will be at Northtown Books (957 H Street) during the next Arts! Arcata (Friday, June 8). The event starts at 7 p.m., and the book will be available for purchase.

###

I

was

running

saw

on

a

job

up

in

Happy

Camp,

and

headed

home

I

made

what

I

thought

would

be

a

short

stop

at

the

Somes

Bar

Store.

The

store

sits

just

above

where

the

rivers

join.

Just

above

that

is

a

jumble

of

boulders

in

the

Klamath

so

huge

that

even

its

vast

flow

is

bent

and

wrapped

into

a

riffle,

a

gray,

grinding

flood

that

has

run

there

since

the

retreat

of

the

last

Ice

Age

and

before.

These

rapids

are

called

Ishi

Pishi

Falls,

and

the river

has so much power

that even

the runs of many kinds of salmonids,

as

they

return

to

spawn

in

their

natal

streams,

need

to

slow

in

what

backwaters

and

eddies

they

can

find.

For

millennia,

and

maybe

forever,

Native

people

have

fished

at

the

falls

with

small

nets

strung

between

long

poles.

There

was

a

village

just

above

there

that

the

Karuk

people

called

Ka’tim’îin.

That’s

the

phonetic

spelling

offered

by

William

Bright’s

brilliant

Karuk

Dictionary.

The

arrival

of

the

white

miners

decimated

the village

just the

same as

it ruined

so many

others.

The great

fish runs

were

reduced

in

number

from

the

sediments

dumped

by

mining

and

by

the

generations

of

too

many

haul

roads

and

too

much

logging

that

followed.

Much

of the Karuk culture

was trampled in those years,

but it

is not forgotten.

Willis Conrad was the first person to take me to the falls. His family had had rights to a fishing spot there on the west side of the Klamath for countless generations, and he was justifiably proud of his skill maneuvering the net and poles. He had to do this perched on a wet boulder over the churning river, and the danger was not lost on him. He told me stories of people who had fallen in the water and were rescued by fellow fishermen. In one of the stories the person was swept away, and his body was found days later along the bank thirty or forty miles downriver in Weitchpec, being eaten by feral pigs. If the stories were to make me cautious, they certainly worked.

Willis Conrad, a member of the Karuk Tribe, was a traditional dip-net fisherman and a friend to the Black Bear Commune in the early days when we who lived there had few local friends. Photo courtesy of Shawnna Conrad.

I should warn about the information I offer about local Natives. I am only half certain if it is right. Some of it I’ve been told by people I know. Some of it, I’ve read here or there. People on the river tell stories of academic ethnographers prowling around a hundred years ago and offering money to elders for stories. Elders are inventive by their nature, and money is an extra spur to invention. So my sources are suspect, I guess. You are warned accordingly.

But this I know: Willis had a certain kind of charisma. His charisma went beyond his ability to lead a fire crew, although he was certainly adept at that. Charisma, the way I define it, includes the ability to coax people into doing something they might not ordinarily do. Different people accomplish persuasion in different ways. Some browbeat you. Others guilt trip you or intimidate you. Willis’s particular gift was to make you feel that some task was something you always wanted to do.

Charlie Thom, who was a Native doctor and a ceremonial leader among the Karuk, told me a story about Willis. It goes back some years to when the Karuk were trying to win official recognition from the feds. Charlie decided it would be useful, politically as much as culturally, to rebuild the ceremonial dance pit at Ka’tim’îin. He says he recruited Willis to the project because he knew Willis would know how to talk people into it. Willis must have told his friends, “You know how you’ve always wished there was a dance pit here again . . . .” The pit got built.

So there I was at the store, and Willis came in. Neither of us was still working for the Forest Service, and we exchanged greetings. To make small talk, I asked him when the next tribal Brush Dance would be. “It starts tomorrow,” he said. I nodded appreciatively, and he added, “They’re playing cards down there at Ka’tim’îin tonight. Let’s go.” Then, as I arranged my excuses in my mind, he added, “You always like that sort of stuff.”

“Indian cards, with the sticks?” I asked, stalling.

“No. Regular cards. They’re playing Ka’tim’îin Schmidt. You’ve played it, huh?”

Minutes later we were down at the ceremonial grounds even though I’d protested that, after a day running chain saw, there was nothing I wanted more at that moment than a shower. A summer day spent running saw coats your skin and your clothes with a fine film of bar oil and wood chips.

“I don’t have any money, so I can’t gamble,” I said. This was not quite true.

“You don’t need money,” Willis said. “I have money.”

Several other Native men were already sitting at the table when we arrived, and they greeted Willis enthusiastically. “Hah, now we’ll get some of that Conrad ishpuk,” one of the gamblers said. I didn’t know many Karuk words, but everybody knew ishpuk meant money.

One of them offered me a beer from under the table and then made a show of not offering any to Willis. He teased back and soon had a beer.

“Put your money out, Willis,” the dealer said.

“I’m not playing. Just deal to my friend,” he answered and dumped a handful of quarters on the table in front of me.

The dealer shuffled a fat deck—it must have been more than one set of cards—and dealt a small hand to each of us. I turned to Willis and mouthed, “I don’t know how to play.”

Willis only grinned, motioned my attention back into the game and slid a few of his quarters into the pot for me. Players laid out cards, and when my turn came, Willis made a gesture that I should play whatever card I wanted. It continued through the hand.

“Well, look at that. Hippie dude has won the whole thing. Who’s this card shark you brought here, Mr. Conrad?” The dealer pushed the entire pot over into Willis’s pile of quarters. I took a congratulatory sip of the beer and wondered how I’d won. Also whether this might be a clever hustle to get hold of any money I might have. Then another sip of the beer. Over the next few hands I won frequently, but not every hand. I started to think I understood the rules, but then something else would happen. It was as though the game was really three games overlaid, each with its own set of rules. As my pile of quarters grew, Willis pocketed a handful. No problem. It was his money. An hour went by. A few of the players, the biggest losers, started to seem annoyed, and that just made them the target of more intense teasing.

I was, by then, in my second beer, my usual limit, but the under-the-table stash had run out. A young Karuk woman, very pretty, had been sitting on the periphery, and one of the men instructed her to bring more from his pickup. When it arrived, he set one in front of me, even though mine was far from finished. I made a show of guzzling that one down and opened the new one. The game continued.

At some point, a Native woman of great age and great dignity approached our table. All of the men slipped their beers out of sight, and Willis nudged me to do the same. “Hello, Willis,” she said.

“Hello, Elizabeth,” he replied. All of the other players nodded with great respect, and so did I.

“Who’s she?” I asked when she moved past us, and one card player said she was Elizabeth Case, an important medicine woman, come to join the Brush Dance ceremonies. Another said she’d been in declining health. It was a good sign that she’d come.

Beers surfaced again, and I was passed another. I didn’t rush to open it. I still needed to drive home. The sun had dropped below the ridge, and one of the people near the dance pit preparing for the dances was looking around for a lamp. One of the card players said his wife would be pissed by his absence, and he left the table, in a shower of good-natured teasing. I turned to Willis, who still had not joined the game himself, and said I needed to leave too. Other players overheard me, and sour expressions crossed their faces.

“They’re not gonna like it if you leave,” Willis said. “That guy left. Why not me?

“That guy hadn’t won all their money. They want a chance to win it back.”

So I played many more hands, winning some and losing others. Whenever my pile swelled with quarters, Willis would scoop up some and dump them into one of his pockets or another. Finally, I announced that I had to leave. Most of the players just broke into good-natured laughter, but one spoke in an angry tone, not to me but to Willis. He spoke in a mix of English and Karuk, so I was uncertain what he said. Willis answered in kind, and one of the other players leaned over to me and said, “If you’re gonna go, you better go now.” The rest of them, even the angry one, all broke into more laughing and louder teasing at that. I slipped away and could hear their voices as I wandered off into the approaching darkness, trying to remember where I’d left my truck.

Several weeks passed after the card game before I saw Willis Conrad again. He had a home not far from the ceremonial grounds at Ka’tim’îin, and I found him there. The house and its surroundings always fascinated me. A steep road descended to it from the main highway, and it was built on a forested bench, part of what I guessed was a very old landslide. There was a long line of abandoned cars in one direction and a full woodshed in the other. The cars were swallowed in blackberry canes, and farther away there was a small deserted cabin disappearing into the thickets of small conifers and more thorny brambles. When I stared hard, I could see signs of what I took to be another even older cabin, slowly sinking into the vegetation. That was just what I could see. I sensed that people had always lived at that place, close to the dip-net fishing places at the Ishi Pishi Falls. Even with the wrecked cars, it seemed as hallowed as an old country church.

But Willis’s house was not so old. He had built a big add-on as his family grew. The new room was a source of personal pride; he told me the story. He had worked lots of different jobs over the years and eventually ended up with the US Forest Service. That was the period when I was assigned to his fire crew. He was not exactly in love with the agency. Lots of its employees felt that way, especially people who were local to the area, and this was even truer of Karuk people. All of the land that had once been theirs was now labeled National Forest. They were ticketed for cutting firewood, penalized for hunting deer for their families, and harassed for catching salmon, with the exception of the dip-netting at Ishi Pishi Falls, where the game wardens looked the other way. Eventually, when the tribe got federal recognition, there was much lip service paid by the government agencies to the new Karuk sovereignty. In this flush of “government-to-government” relations, it was agreed that the US Forest Service installation at Somes Bar should go to the tribe. Some of the structures were left for the tribe, and others were dismantled. One in the teardown category was what had been the main office of the Ukonom District. Willis made the winning bid for the demolition and then hauled the materials he could reuse to his own place, a half mile away. I could tell that he took great pleasure in tearing down a building that had been the source of so much aggravation over the years. He even reused the office doors, prominently labeled United States Forest Service, or propped them up in his yard like a hunter might hang a trophy head on his wall.

Willis was working under the hood of a car when I showed up, but he invited me into the house to visit. I wanted to tell him a story about my daughter, Erica Kate, who was then ten years old. When she was just a baby, Willis had given her a name in Karuk language, the word for mountain lion. Years earlier, Willis had named Slate, Erica Kate’s big brother, vírusur, the Karuk word for bear. That made sense. Even as a child, Slate seemed bear-sized.

I always have trouble pronouncing the word for mountain lion, which is yupthűkirar. Try pronouncing that. Anyway, I told Willis that Erica Kate and a young friend had seen a mountain lion in the brush while walking home from the swimming hole at Grant Creek. Erica Kate and her friend had carefully backed away, and, as soon as they were out of its sight, they ran like crazy to get home.

Willis shook his head and said they shouldn’t be afraid. “The mountain lion will protect Kate,” he said. He called her Kate in those days. Everybody called her Kate.

He offered a beer, and I declined, but I thanked him for taking me to the card game. He laughed and said, “You thought you wouldn’t do very good.”

“I still don’t think I’m very good.”

“Well, all those guys who lost money thought you did okay,” he said and laughed again.

“But really,” I said. “How come I won so often?”

“Well, if you really didn’t get the game, then maybe you were just lucky.”

“Lucky? Nobody’s lucky that much of the time.” I could tell when Willis was being evasive. He’d get this sly smile and you knew.

He scratched his head and said, “I’ve been watching cards a long time, and luck plays a part. People don’t give it enough credit. And beginner’s luck is especially strong sometimes. Maybe you were having beginner’s luck.”

It was not a very satisfying explanation for me, but I finally said, “I have a couple of other questions.”

“Fire away,” he said. He was happy to change the subject.

“Is Ka’tim’îin Schmidt what people call Indian cards? I’ve always heard about Indian cards.”

“Indian cards is different,” he said, reaching across to the shelf behind him. He grasped a small bundle of sticks, untied the short deerskin lace that held them, and passed them to me. “You never seen Indian cards?” They were a little thicker than matchsticks and of sturdier wood, maybe hazel that’s also used for baskets. They looked to be nine or ten inches long, and there were more than a dozen of them. I squeezed them in my hand to get the feel of them, and Willis nodded approvingly.

I returned them to him, and he showed me that there was a small black mark around the center of one of the sticks. Then he put them behind his back and divided them into both hands. He held both hands out and said, “Which hand has the marked stick?”

I picked a hand and was right. Next turn I was wrong. He passed me the sticks, and I tried, although I was really not certain myself how I’d divided them. Then he explained to me a long web of complex thinking that he used to outwit other players. My mouth may have hung open to hear such a maze of feint and deception for what, it seemed to me, was little more complex than flipping a coin heads or tails. On top of that, sometimes bystanders in real games were beating a drum and others might be singing or chanting with other people placing side bets or teasing or just generally making a racket. More than coin tossing, I agreed.

He wrapped the sticks together again with the deerskin lace and handed the bundle to me. “These are for you,” he said.

I was touched by the gift and thanked him. Then I thanked him another time for the way he befriended us back when we lived at the commune. He pursed his lips and finally said, “You know what I think of white people. When I met you, you didn’t seem white. Sometimes I watch you now with a job and a good truck and a big house, and I wonder if you’re becoming too white.”

I was unsure of what to say. Everything that came into my head was too glib or too defensive. So I didn’t say anything and just stared down at the bundle of sticks he’d given me. After a while Willis said, “You said you had two questions. You only asked one.”

“Yeah,” I said, happy to stop reflecting on whether I was backsliding into some white-people cultural destiny. “What I want to know is what that guy said. The one who growled at you when I said I was gonna leave the Ka’tim’îin Schmidt game. He mostly spoke in Karuk.”

Willis thought back for a minute and then another big smile crossed his face. “You don’t wanna know,” he said.

###

(c) 2018 by Malcolm Terence. Republished by permission of Oregon State University Press.

CLICK TO MANAGE