“For my part, I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move…”

— Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes, 1879, Robert Louis Stevenson

###

RLS was a barely published author, living on the goodwill of his parents, when he took a trek through southern France in the company of Modestine. He didn’t have a knack for picking female company: the American woman he’d been courting returned to her husband, and Modestine was exceptionally stubborn, even for a donkey.

His account — part outdoor saga (one of the first to be published), part history (the area had seen bitter religious wars) and part personal philosophy (think The Snow Leopardabsent snow and leopard) — became a best-seller. Kidnapped, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Treasure Island would follow, establishing his reputation as one of Britain’s most beloved authors.

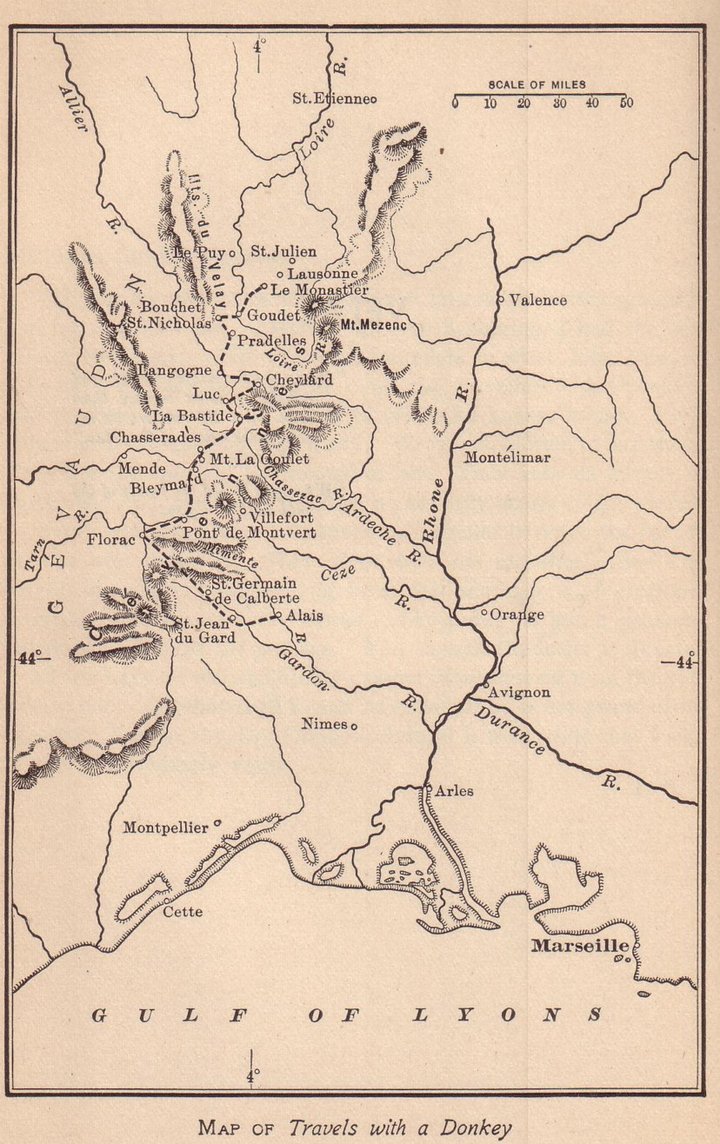

RLS route through the Cévennes with Modestine (Public domain).

Travels with a Donkey inspired the title of the last book written by then-ailing John Steinbeck, who circumnavigated the U.S. in a camper van named “Rocinante” (after Don Quixote’s horse). Like “Donkey,” Travels with Charley became an instant success. (Unlike “Donkey,” it was largely fiction dressed up as fact.)

Steinbeck’s “Charley” (LordHarris/Creative Commons)

My personal steed of choice has no name (and “Nameless” has already been appropriated by my stuffed baby gorilla), but she occupies as fond a place in my heart as Stevenson’s and Steinbeck’s modes of transport. She — I think of her as such — is a one-speed Dahon 20-inch wheel folding bike, weighing in at about 25 pounds and — with wheels removed — conforming to the magic “62-inch” rule for free passage when flying internationally. (One piece of checked baggage goes free if the length + breadth + height < 62 inches, and the weight < 50 pounds.)

Unnamed (but not nameless) Dahon folding bike (Barry Evans)

Ditto, folded

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways. Having just a single gear eliminates all sorts of problems (don’t get me started on broken drop hangers); the two folding mechanisms are simple, strong and fast; the rear coaster brake takes me back to childhood; a bare minimum of tools (plus spare tube) are needed to keep her in shape; a foot pump hides in the saddle post; and — how to put this? — she just works. No muss, no fuss, form is function.

For a relatively youthful lady, she’s seen more of the world than many of her peers, and, as best as I can tell, she’s willing and anxious to see yet more. Speaking of her peers: she’s a dying breed. Soon after I bought her (“adopted” would sound better), Dahon ceased production of their 20-inch one-speed models. Apparently, insufficient customers had been enticed by her many charms. Which is a shame: I believe the future of commuting will involve folding bikes which can be readily schlepped on buses and trains, small enough to be stored under a seat, light enough to be carried up a flight of stairs or so. (Our current digs finds us on the fifth floor, 78 steps.)

Not that she’s perfect, any more than were Modestine or Rocinante (four-legged or four-wheeled). Something about a titanium frame sounds pretty good. Ditto belt drive. But dissing her for shortcomings feels rather uncharitable, like wingeing about Siri for her stupid sense of humor. When Travels with a Folding Bike (as yet, unwritten) makes the NYT best-seller list, maybe then I’ll check out the latest and greatest models. Until then, she’s my second-best pal.

CLICK TO MANAGE