Ten Pin Building | Google Street View

In recent years the nondescript Ten Pin Building, located at 793 K Street in Arcata, has been primarily utilized as the North Coast Co-op’s warehouse. But longtime locals will remember the meaning behind the building’s name: For decades the location was home to Arcata Bowl, a bowling alley that closed way back in 2000 and, for a time, apparently unknowingly handled countless deadly, industrial waste-filled bowling balls.

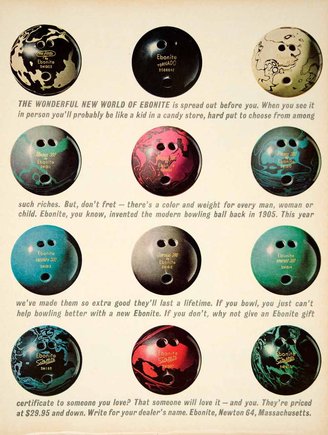

A 1960s ad for Ebonite bowling balls

This week a jury in Los Angeles County ruled against asbestos supplier Honeywell International Inc. and awarded $4.4 million to the family of the late Donald Vanni who co-owned Arcata Bowl from 1957 to 1986. Donald died in 2013, the result of mesothelioma caused by years drilling out custom-sized finger holes in asbestos-filled bowling balls.

Here’s the story, courtesy a celebratory press release issued by the Vanni family’s legal team at law firm Waters Kraus & Paul:

Donald worked at the bowling alley seven days a week trading off opening and closing shifts with his brother. One of Donald’s responsibilities was drilling custom-fit finger holes in the bowling balls that the Arcata Bowl sold.

Asbestos, used as a filler in plastic Ebonite bowling balls, was supplied by Honeywell in the form of discarded brake lining dust. The brake dust was the waste product of Honeywell’s Bendix brake manufacturing plant in Troy, New York. In the late 1960s, documents show that the Bendix plant was generating 15 tons of asbestos-laden brake dust each day. But, rather than pay money to safely dispose of this asbestos-laden waste, Honeywell opted to sell it as a filler in commercial products, including Ebonite bowling balls.

Ebonite was one of the most popular balls in the 1960s and 1970s, including at the Arcata Bowl, and was endorsed by professional bowlers such as Don Carter and Earl Anthony. Donald Vanni routinely drilled Ebonite balls in a small room, with no protection, for years. No one ever told the Vannis that the Ebonite balls contained asbestos.

Donald was in good health until he was diagnosed with pericardial mesothelioma in 2012. He and his wife had lived an active lifestyle. They would regularly go fishing, golf, and were active members in their Church. The Vannis also enjoyed sporting and entertainment events, and visiting their grandchildren. Donald died of mesothelioma in 2013, leaving behind two adult sons and his wife of 55 years.

The jury found that Honeywell’s asbestos waste presented “a danger to persons using the products as intended.” They said that Defendant Honeywell failed to adequately warn of the potential risks and Honeywell’s negligence was a substantial contributor to Donald’s mesothelioma.

“This was completely preventable,” said Sam Iola, an attorney at Waters Kraus & Paul who represented the Vannis family. “The Vanni family should not have lost Don nine years early due to Honeywell’s greed. Asbestos brake dust should have never gone into a single bowling ball.”

“Honeywell refused to take responsibility here, and we held them accountable,” said another WKP attorney, Peter Kraus, in the release. “I am so happy for the Vanni family.”

CLICK TO MANAGE