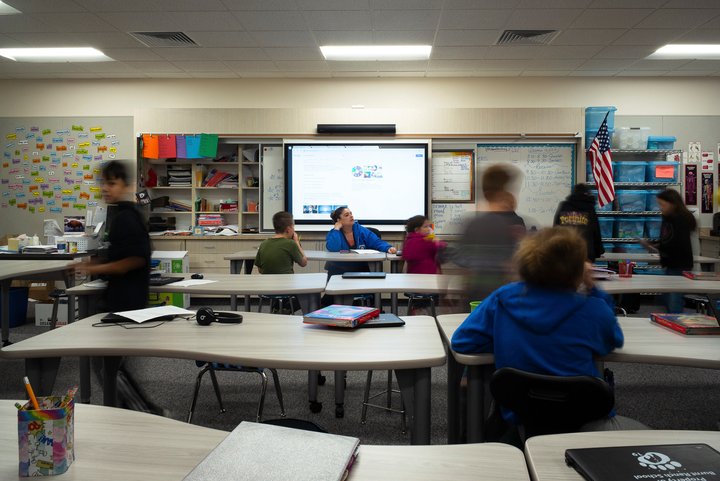

A new classroom at Burnt Ranch Elementary School in Trinity County. After the school discovered a massive mold problem, the state-subsidized repairs tapped out district reserves and took three years. Photo by Dave Woody for CalMatters

###

The foul odor had invaded almost every classroom. It was late March 2017, and Burnt Ranch Elementary was teetering on disrepair. The heating and ventilation systems were so unreliable that educators and staff in the small Trinity County school had been warming up frigid classrooms with portable heaters. Water leaked through the light fixtures, spilling onto the floor.

Kathleen Graham, the superintendent and principal, knew something had to be done, but raising the money through local bonds – California’s main driver of school facilities funding – was next to impossible for the single-campus, 100-kid district. The alternative wasn’t much better: Competing with larger, better financed and more amply staffed districts for a piece of a state bond passed in 2016, a process that involved navigating California’s byzantine School Facilities Program.

As winter became spring, Graham recalled, the need only became more pressing. ‘Our buildings,’ she said, ‘just went off the charts with mold.’

But as winter became spring in rural Northern California, Graham recalled, the need only became more pressing. “Our buildings,” she said, “just went off the charts with mold.”

Health and safety cases like Burnt Ranch have become top-of-mind as California voters weigh a new statewide school bond that would generate $15 billion for schools, community colleges and universities. Proposition 13, slated for the March ballot, would not only raise much-needed funding for maintenance and construction, but also end the first-in, first-out application system for state bond money that disadvantages small, poorer and rural schools.

The current system has been criticized by schools, advocates and financial experts as overly favorable to large, richer districts. Larger districts, they say, have the resources not only to put local bond measures on the ballot and pass them, but also to hire the staff needed to navigate and complete the cumbersome state paperwork required to compete for and leverage the state matching funds.

That setup, CalMatters found last year, exacerbates broader structural inequities: Public schools in California’s wealthier communities have long reaped far more local bond money than poorer districts, averaging more than twice as many local bond dollars per student since 1998 as the most impoverished districts. In turn, districts use those local bonds to qualify for a limited pot of state bond money.

The state’s system is “not a fair playing field,” said Tim Taylor, executive director for the Small School Districts Association. “You’re asking a little district like Tulelake, which is by Modoc County, to compete with Long Beach or Elk Grove, who have full facilities departments with experts.”

The bond proposal – the result of eleventh-hour negotiations between Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office, state legislators and advocates – would generate much needed money for campus construction and renovation, costing $740 million per year over the next 35 years to repay with interest, according to a legislative analysis. It also overhauls several regulations, aiming to make the state’s school bond program more equitable.

Prop. 13 would introduce a new points-based system in which critical health and safety projects, such as mold and asbestos, gain top priority and a space at the front of the line for state facilities assistance. Next in line would be districts (such as Burnt Ranch) that qualify for financial hardship funding, followed by projects aimed at remediating lead in drinking water.

The state bond, which at last glance was polling under 50% approval, also would earmark $5.2 billion – the largest share of the $9 billion for K-12 schools – for school modernization projects. Schools affected by natural disasters, such as wildfire, would be eligible for immediate assistance under Prop. 13, and schools for the first time would be allowed to spend state bond dollars on preschool facilities.

Prop. 13 would also raise local bonding capacity for California districts, meaning they would be able to place larger school bonds on local ballots. And 10% of the state bond’s $9 billion for K-12 schools would be reserved for small school districts – those with 2,500 students or less. The “smalls,” as rural educators refer themselves as, would receive extra technical assistance under the measure.

Hope for the ‘smalls’

The Trinity River near Burnt Ranch. The school is in a heavily forested region of Trinity County 60 miles from the nearest city. Photo by Dave Woody for CalMatters

For all the bells and whistles included in a dense bond measure whose bill text is nearly 30,000 words, state leaders and advocates point to the bond’s renewed focus on equity as having the most potential impact on schools. Newsom, who said he will campaign for Prop. 13, called the changes to how the state would prioritize school districts’ applications an “incredibly important reform.”

At a recent signing ceremony for Assembly Bill 48, the legislation putting the state bond measure on the ballot, Newsom recalled traveling to the state’s remote corners as part of his years-long campaign for governor. There, he toured school facilities in substandard condition and heard from school officials who told the governor that “we’ll never see those school bond dollars because of the way the current rules are written.”

‘You go into some of these parking lots, these sheds without air conditioning and lead, they’ve got asbestos in those facilities – that’s not who we are.’

“You can’t look in the eyes of these kids and make an argument that the facilities that so many of them are being educated in are appropriate,” Newsom said.

“You go into some of these parking lots, these sheds without air conditioning and lead, they’ve got asbestos in those facilities – that’s not who we are. We’re capable of so much more.”

Eventually, the state awarded the Burnt Ranch district $14 million to rebuild its school, half of which came under the category of “financial hardship” funding. This bucket of money is reserved for California’s poorest districts with critical facilities issues that present “an imminent threat to the health and safety of pupils,” such as mold, asbestos, dilapidated water systems and internal flooding.

Though crises like Burnt Ranch’s are rare across California’s 1,000 public school districts, a historical database of emergency school closures published earlier this year by CalMatters shows they’ve grown far more common in recent years.

CalMatters found at least 38 incidents in 29 schools where mold or asbestos was cited by local school officials as the reason for temporarily closing down campuses. Of those 38 school closures, which affected more than 11,000 kids, all but five had occurred since 2014.

And disruptions due to crumbling facilities are also more likely to affect poor schools, that analysis found. At least 370 closures in CalMatters’ database involved breakdowns in school facilities – such as broken water pipes, inoperable septic tanks, harmful traces of mold or asbestos, or water quality issues such as broken wells or E. coli.

Of the 176 districts reflected in this group of closures, 57 had not passed a local bond since 1998, according to a separate CalMatters database that detailed inequities in funding for local school facilities.

One school’s ordeal

Burnt Ranch was closed for more than two years while the structures were completely rebuilt. Photo by Dave Woody for CalMatters

For Burnt Ranch, passing a local bond is a non-starter because the district’s tax base is so small that “we don’t have enough people here to support a bond,” Graham said. That, in turn, has meant little funding to adequately modernize a campus where the main structure was built in 1961.

“There is this reality that as you ignore [facilities] needs, problems compound. What is a small leak in a roof can become a mold infestation if not dealt with in a timely manner,” said Shin Green, an Oakland-based school infrastructure financing consultant. “And whether or not you have the resources to deal with it in a timely manner is really a function of your bonding capacity or ability to access hardship funding.”

‘There is this reality that as you ignore [facilities] needs, problems compound. What is a small leak in a roof can become a mold infestation if not dealt with in a timely manner.’

After its mold crisis forced it to shut down school for three weeks, Burnt Ranch leaders had to search for temporary classrooms. Every school building had toxic mold and water damage, according to testing results.

Relocating to another school wasn’t an option. Tucked inside Trinity County’s dense forests, Burnt Ranch is more than 60 miles from the closest city. So Graham, the superintendent and principal, and the Burnt Ranch school board decided to spend the savings they planned to use to get matching state bond funds to pay for seven portable buildings and a restroom on the edge of one of the school fields.

In a letter sent to the State Allocation Board pleading for immediate assistance, Graham described how the district’s barebones set-up affected students’ education. No gym meant no space for physical education, sporting events or school assemblies.

“Lack of any conference rooms, a special education/speech room, a library, and a separate room for counseling and intervention services has also negatively impacted the district’s ability to provide needed programs,” Graham wrote.

Between April 2017 and the start of the 2019-20 school year, students and teachers at Burnt Ranch operated without a gymnasium or cafeteria, walked daily through the school’s construction site to get to class and ate lunches outside as staff prepped and hauled in meals from 15 miles away.

“That was our life for more than two years, and it was amazing that any of us survived it, just mentally, because it was really tough,” Graham said.

It took more than a year for Burnt Ranch to get the entirety of its state assistance. The process involved testing, paperwork, 4-hour trips to Sacramento and legislative intervention, Graham said. In the meantime, the mold crisis wiped out most of the district’s savings, and Graham struggled to maintain construction costs below what Burnt Ranch could afford with its state assistance. Many contractors, she said, either were unwilling to take up a project so remote or with such high hiring and personnel costs.

Finally, on a recent autumn Friday, students at Burnt Ranch Elementary School walked into newly-built classrooms with smartboards. And in the rebuilt gymnasium, a technician from the Dell’Arte International School of Physical Theatre in nearby Blue Lake was setting up lights for a holiday play. After nearly three years, Burnt Ranch had its school back.

But facilities issues remain. The school’s small well system has grown older and less reliable. Burnt Ranch needs a generator — a rural must for power outages due to inclement weather. State records show that, since 2017, the school has lost 11 instructional days due to inclement weather and blackouts. This school year alone, Burnt Ranch closed for three days due to the widespread utility power outages aimed at preventing catastrophic wildfires.

“We’re going to have to get some assistance for that,” Graham said. “We don’t really have any money left now that we built this building.”

###

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE