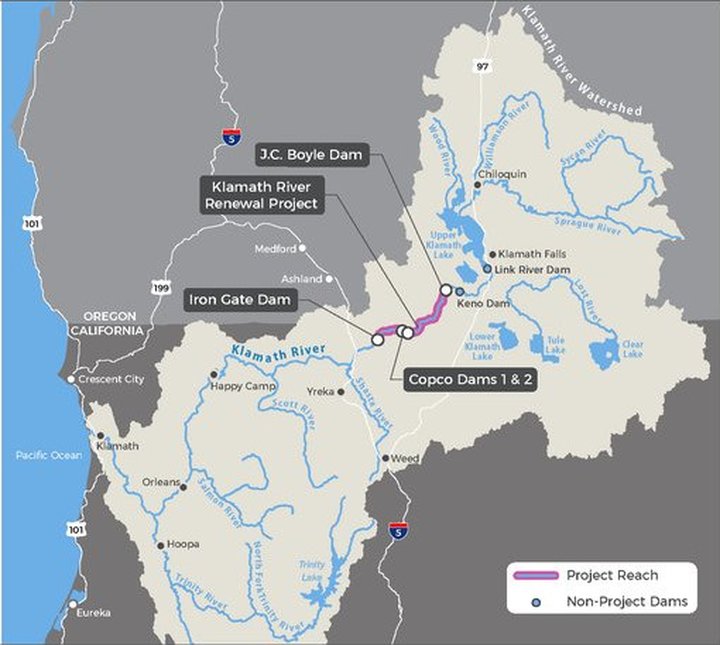

Map via the Klamath River Renewal Corporation.

###

As a Senior Environmental Scientist and Environmental Program Manager for the California Regional Water Quality Control Board’s North Coast Region, I’ve spent more than a decade of my career studying, developing and implementing pollutant control and ecological restoration programs for the Klamath River.

If you’ve ever visited the reservoirs behind the lower Klamath dams between the months of June and November, you know what that brings. Warm, nutrient-rich water are captured in deep pools, creating ideal conditions for the growth of Microcystis aeruginosa, a type of freshwater cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) that produces harmful algae blooms.

It produces a potent liver toxin (microcystin), and if you are in the water with Microcystis aeruginosa, it can cause skin rashes. If people, pets, or other animals ingest it, it can cause stomach cramps, nausea, diarrhea and liver and kidney damage. High levels of microcystin have even caused deaths in pets, cattle and wildlife. Trust me, you want to stay as far away from this stuff as possible.

In the reservoirs behind Copco 1, Copco 2, and Iron Gate dams, the concentrations of the toxic blue-green algae so often exceed levels considered safe that Public Health Advisories are posted, and it is recommended that all contact with the water be avoided. The toxin is so stable that even boiling water from the reservoirs does not destroy the microcystin or its toxic potential.

But here’s the interesting finding from our research. Many have long assumed that the toxic algae is imported into the reservoirs from Upper Klamath Lake. They believe that if we don’t do something about Upper Klamath Lake, that the toxic algae will still persist down river with or without the lower Klamath dams. That is not true.

A recent study (Otten and Dreher 2017) showed that the toxic algae in Copco and Iron Gate is often a distinct population that is “home grown” in the reservoirs and is often genetically different from that found in Upper Klamath Lake. In addition, Microcystis does not grow well in turbulent free-flowing rivers so that even if toxic algae are transported into the river from upstream, the harmful algal blooms will not occur without the calm and warm water created behind the dams.

What these studies tell us is that removing the four lower Klamath dams and creating a free-flowing river would eliminate the ideal conditions that allow the Microcystis to grow to dangerous levels and the public would no longer have to avoid the toxic waters for six months out of the year.

Sincerely,

Clayton Creager

Watershed Stewardship Coordinator

California Regional Water Quality Control Board North Coast Region

CLICK TO MANAGE