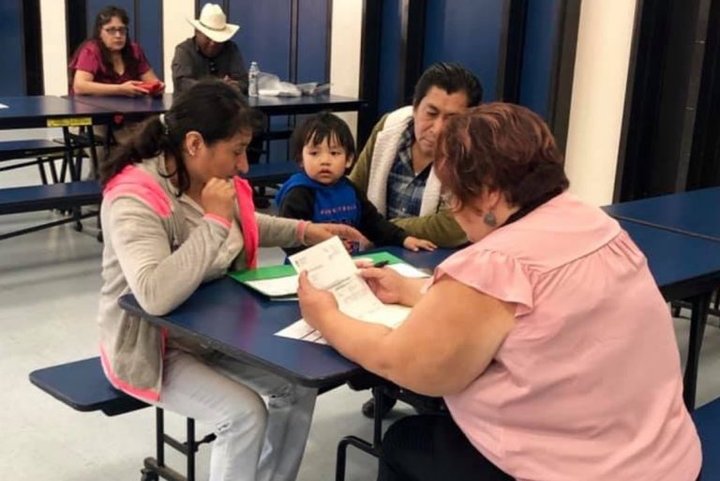

Berenice Solis volunteers as a tax preparer to help low wage earners in Kern County claim tax credits. Photo by Susana Espinoza, via Berenice Solis.

###

When Berenice Solis of Bakersfield received a direct deposit of $6,775 from the government this past March, her mind raced.

She could finally take her three daughters, ages four, six and nine, on a trip to Disneyland. Then she thought about her goal of buying a house. Or upgrading her car, which is starting to feel cramped as her girls grow.

“I couldn’t believe it at first,” said Solis, 40, a part-time teacher’s aide in Bakersfield. Her husband, Jose, is an elementary school teacher. “I was like, ‘Oh my God, I can’t believe this is the money we’re going to get!’ We can do so much.”

The money came from the Earned Income Tax Credit, one of the country’s principal tools to boost the incomes of low-wage workers who are struggling to make ends meet. And when Solis files taxes next spring, she can expect her credit to grow because, at Gov. Gavin Newsom’s urging, California’s new budget will more than double the state’s portion of the program.

“The issue of our time is the issue of poverty, the issue of social mobility,” Newsom told a crowd in early June, adding that the expansion is “perhaps the most significant anti-poverty initiatives that we’ll be passing this year.”

Newsom’s expansion is the largest to date, extending the credit to an estimated 3 million Californians, up from 2 million currently. The cost of the program, which piggybacks a larger federal tax credit, will grow from $400,000 per year to $1 billion.

It will give workers with young children, like Solis, a boost of $1,000 and expand the credit to all workers who earn up to $30,000 annually. The boost for workers with kids under the age of six will target the six in 10 households with young children who struggle each month to meet basic needs.

By raising the maximum eligible income, Newsom also ensured that people working full time at minimum wage won’t lose the credit when their hourly pay rises to $15 by 2022.

“There are so many folks really living on the edge in California today,” said Assemblyman Phil Ting, a San Francisco Democrat who championed expansion of the credit, after lawmakers voted to pass the governor’s expansion last week. “Having a few hundred more dollars or even a few thousand more dollars makes a huge difference to their everyday lives.”

California’s program models after the federal tax credit for the working poor, the rare big buck anti-poverty program with bipartisan support.

When President Ronald Reagan signed the credit into the U.S. tax code in 1986, he hoped it would push people to work more, because the credit grows as people add more hours to their work week.

Over time, it also became the country’s main tool to bridge the growing gap between stagnating paychecks and the cost of living for low income workers, according to Hillary Hoynes, a UC Berkeley economics professor who studies the credit.

Researchers link the $63 billion program to better health for mothers, higher birth weights for babies, as well as better math and reading scores in elementary school, higher graduation rights from high school and college, higher earnings in adulthood, and even fewer suicides.

Under Gov. Jerry Brown, California became the twenty-sixth state in 2015 to create a state credit that piggybacks on the federal program.

While most states give a flat percentage of the federal credit, California did its own thing. The goal was clear: give a big boost to only the state’s neediest workers, those making less than $14,000 per year.

It was also a diagnosis of a problem. California consistently ranks as the state with the highest poverty rate, when taking into account the cost of living. And over two million Californians, or 5.6% of the state, live in deep poverty, defined as living on less than half of what’s required to meet basic needs.

Since then, lawmakers expanded the program twice, offering it to people with higher incomes and self-employed workers. The state even went beyond the federal program to offer the credit to young adults and seniors without dependents.

Back in 2015, hopes for the program were high: “People who work every day should not live in poverty,” Assemblywoman Shirley Weber said. The credit would help “lift thousands of folks out of deep poverty.”

Weber turned out to be right. In 2016, the state credit pulled approximately 27,000 people out of poverty and 13,000 out of deep poverty, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. The state and federal tax credits together lifted about 784,000 people out of poverty.

But the benefits are not fully realized. As many as one million eligible Californians didn’t claim it last year, mostly workers who are not used to filing because they don’t earn enough income to owe taxes. To bridge the gap, the state allots $10 million annually to fund outreach.

Until more eligible Californians start claiming the credit, researchers can’t measure how much it encourages Californians to work more.

Even so, Hoynes expects the California program to get a similar bang for its buck as the federal credit. Her research shows that for some groups, such as single mothers, half of the credit’s poverty-reducing power comes from recipients being incentivized to work more. That means a dollar invested in the federal credit leads to more than a dollar in increased family income.

One group still can’t claim the credit. In the final rounds of state budget negotiations, undocumented immigrants who file taxes with Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers, or ITINs, were cut from the expansion.

As many as 388,000 ITIN filers would have qualified for the credit, while as many as 297,000 children would have benefited, according to the California Budget and Policy Center. Most of those kids are U.S. citizens with undocumented parents. That’s because only households in which every member has a Social Security number can currently claim the state and federal credits.

For Berenice Solis, the exclusion hit close to home. A volunteer tax preparer herself, Solis often travels to Central Valley communities to help others file their taxes. There, she encounters many undocumented workers who can’t claim the credit.

“It gets me frustrated. I go out to the rural areas, and a lot of our taxpayers are ITIN holders,” Solis said. “Anybody who is working and doing the right thing should get the benefit.”

Solis and her husband decided to use the $6,775 to pay down debt and improve their credit score, so that next year, they can make a down payment on their dream car, a Toyota Sienna.

She sees the same story play out for others. Sometimes it’s enough to pay a bill, take a trip, or even buy a car. Other times, it covers a few meals.

“If they can have that money to take their kids out to McDonalds, that’s incredible,” Solis said. “And just eat and not worry about ‘Where am I gonna get this $100?’”

###

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE