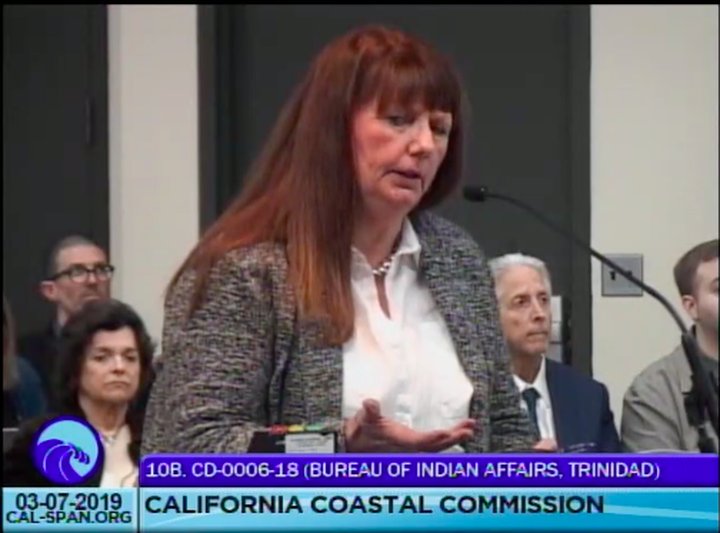

Trinidad Rancheria CEO Jacque Hostler-Carmesin addresses the California Coastal Commission Thursday morning. | Screenshot of streaming meeting video.

# # #

The Cher-Ae Heights Indian Community of the Trinidad Rancheria cleared a significant hurdle this morning in its effort to place 10 acres of property along Trinidad Harbor in federal trust status.

The California Coastal Commission voted 8-to-0, with one abstention and a recusal by Commissioner Ryan Sundberg (a Rancheria member attending his last meeting in this position), finding that the Rancheria’s plans are consistent with California’s Coastal Management Program.

Effectively, this decision puts the ball back in the court of the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), which has already conducted an environmental assessment but has yet to rule on the thorny matters of property title and tribal land disputes.

Representatives from both the Yurok Tribe and the Tsurai Ancestral Society, among others, made the trip down to Los Angeles, where today’s Coastal Commission hearing took place, to urge the commission to deny the Rancheria’s application.

Dawn Baum, deputy general counsel and spokesperson for the Yurok Tribe, told the commission that many other opponents of the project were unable to make the trip south, and she argued that the Rancheria’s application leaves many questions unanswered. For example, she disputed the Rancheria’s traffic estimates for a planned visitor center near the Trinidad pier, and while the Rancheria has vowed to maintain public access to the 10 acres in question, Baum questioned how enforceable that vow really is.

But the Yurok Tribe’s primary concerns center on the protection and management of lands they consider sacred parts of their ancestral territory.

“This is our homeland, and we have the potential to be excluded in perpetuity from one of our sacred landscapes,” Yurok Tribal Councilmember Mindy Natt told the commission.

Rancheria representatives, meanwhile, defended their standing as a tribal entity and described the property improvements that they’ve made since purchasing the land back in 2000. Those improvements include the replacement of the old pier, which was accomplished with help from state grant money, and a project to mitigate stormwater runoff in the harbor parking lot. (The Rancheria has a more extensive stormwater project planned if the land is granted federal trust status.)

Rancheria CEO Jacque Hostler-Carmesin told the commission that the Rancheria has “received a lot of biased and prejudiced statements” but has in fact been motivated by environmental stewardship and self determination, not profit.

Bonnie Neely, a former Humboldt County supervisor and coastal commissioner, vouched for the Rancheria, saying the nonprofit tribal entity “stepped up” when the harbor property was for sale and worked hard to comply with the Coastal Commission and local laws. The result is a “fantastic asset” in the new pier, she said, calling the Rancheria “a great partner.”

But Lucas Garcia, culture monitor for Yurok Tribe speaking on behalf of the Tsurai Ancestral Society, complained that neither group was consulted in the Rancheria’s application.

“We believe this is significant due to our status as documented lineal descendants of Tsuria,” Garcia said, noting that the descendants of the Tsurai village inhabitants never sold any of their land rights.

Coastal Commission staff, however, sided with the Rancheria’s government affairs coordinator, Shirley Laos, who said, “The Bureau of Indian Affairs is responsible for sorting out tribal issues, not the Coastal Commission.”

A representative from the BIA, Chad Broussard, was on hand, and he explained that while the bureau is ready to clear the Rancheria’s request environmentally, the BIA’s realty division is still “relatively early” in the process of clearing the property titles, among other real estate issues. That process will include a public comment period, Broussard said.

When the public comment period for today’s hearing was over, Commissioner Erik Howell, representing the South Central Coast, made a motion to approve the staff recommendation, and his motion was quickly seconded.

Coastal Commissioner Maricela Morales.

But Commissioner Maricela Morales, who represents the Central Coast, voiced impassioned opposition to the motion, saying it is “inappropriate and unjust” to vote on a controversial matter concerning native peoples, in particular, when the hearing is so far away from those it would impact.

Noting the state’s history of displacing and disenfranchising Native Americans, Morales said, “Accessibility to a public meeting, to at least have your voice heard, that is such a basic threshold of justice.”

But commission staff explained that, with the strict timelines imposed by the BIA’s application and the Coastal Zone Management Act, today’s meeting was the commission’s only opportunity to vote on the matter. And if they didn’t vote on it, the application would be deemed approved.

Commission Chair Dayna Bochco also noted that there’s still more work to be done, more hurdles to be cleared, before the land is granted federal trust status.

Sundberg had apparently removed himself from this proceeding entirely: He wasn’t even in his chair when the matter was being deliberated.

Morales, who had vowed during her comments to vote no, instead abstained from the vote. All other voting members of the commission voted yes.

CLICK TO MANAGE