The site of Paradise Community Village, a low-income housing complex that burned in the Camp Fire last year. Photo by Anne Wernikoff for CalMatters

###

Nancy Rich wants to go back home.

It’s not just the longer commute that’s wearing on her. Rich, 65, drives an hour each way from her one bedroom apartment in Marysville to her job in the mailroom at the Chico Enterprise-Record newspaper. She works a full swing shift, meaning she doesn’t get home until about 3 a.m.

It’s not just the annoying bathroom leak, which she has to keep stuffed with bath towels, or the rumors of car break-ins and burglaries she hears from her neighbors.

“It gets very lonely,” said Rich, a grandmother of eight. “I don’t know anybody in Marysville, that’s the biggest thing. Everyone here has been polite, but it’s just not home.”

Home for Rich used to be Paradise Village, a 36-unit low-income housing complex that along with nearly everything else in the quiet Central Valley town of Paradise was obliterated in last year’s Camp Fire, the most destructive wildfire in state history.

Rich and many of the other 89 former residents of Paradise Village want desperately for the federally subsidized housing to be rebuilt quickly. So do local officials. Paradise Village represented the town’s only housing stock specifically reserved for poorer residents in an area beset by a disaster-induced housing squeeze.

Nancy Rich outside of her apartment in Marysville, CA. Rich misses the community from her housing complex in Paradise and feels lonely in her current living situation. Photo by Anne Wernikoff for CalMatters

But the nonprofit developer and investors pushing the rebuild are worried about an unexpected obstacle they say threatens to derail the project, a challenge that those rebuilding market-rate homes in Paradise don’t have to confront: an obscure federal deadline to rebuild low-income housing within two years.

Paradise Village originally was financed through the federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit program, and Internal Revenue Service rules dictate that any destroyed affordable housing must be rebuilt and reoccupied within 24 months or the investors in the project have to repay the federal government. The IRS sometimes waives those rules, but the people who want Paradise Village rebuilt are concerned.

“Our challenge is I don’t think that rule contemplated the type of devastation that happened with the Camp Fire,” said Kris Zappettini, vice president of the Community Housing Improvement Program, the nonprofit developer that owned and operated Paradise Village.

Only 12 homes in all of Paradise have been rebuilt and reoccupied so far out of 10,000 destroyed, according to local officials. Cleanup crews just finished removing more than 3.6 million tons of debris, more than was hauled away from Ground Zero after the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Basic infrastructure — potable water, for example — has only recently been restored or is still in need of significant repair.

The Paradise Village developer cited these reasons in a March letter to the IRS requesting a four year rebuilding window. It has not heard back yet, and its investors are concerned.

Without that IRS extension, said Zappettini, “it doesn’t get built.”

An IRS spokesperson said the agency does not comment on specific taxpayer situations.

“Taking a part of Paradise away”

Rich has lived most of her life in Paradise. She went to elementary school there, as did many of her children. When the owners of the apartment she was renting in 2013 prepared to raise rents after a remodel, she moved into a one-bedroom apartment in the new Paradise Village. Because the town lacked a traditional sewer system , apartment buildings were few and far between, let alone apartments set aside for residents at her income level.

Rich loved the place. Unlike the stereotype of dilapidated eyesores some associate with low-income housing, Paradise Village was modern and well maintained.

“You felt safe walking around and you stopped and talked to people and their kids,” she said. “It was home.”

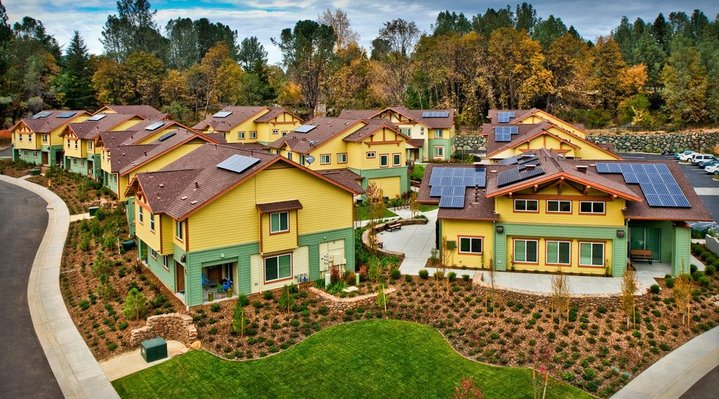

Paradise Village before the Camp Fire. The complex was the largest low-income housing project in Paradise. Photo courtesy of Community Housing Improvement Program.

Paradise Village isn’t the first low-income housing complex to run up against the two-year IRS rebuilding window.

After Hurricane Maria destroyed several low-income housing complexes in Puerto Rico in 2017, the IRS granted a one-year extension for reconstruction. It similarly allowed another year for rebuilding when in 2013 a 72-unit affordable housing project in the Bay Area burned down. (That project ultimately was not rebuilt, and the nonprofit developer did have to repay investors, although the developer does not blame the IRS for that).

But investors in Paradise Village have yet to hear a resolution. And the clock is ticking.

“Many investors at this point in time probably would have said to its nonprofit developers ‘We just want our money, you’re on your own,’” said Maria Duarte, director of asset management for Merritt Community Capital, which invested nearly $2.7 million in the project. “We haven’t taken that position, and we’re going to stay with them as long as we possibly can.”

Billions in federal and state dollars have been spent so far trying to rebuild Paradise. While some of those funds come with strings attached, the timelines are typically far more generous than two years.

Paradise recently received millions in grant funding from the state to loan out to underinsured homeowners so they can rebuild. Town officials have three years to make those loans, giving homeowners even more time to actually rebuild.

Two years is “a pretty tight timeline,” said Collette Curtis, a senior management analyst for Paradise who’s helping coordinate rebuilding efforts.

The site of Paradise Community Village, a low-income housing complex that burned in the Camp fire last year. Photo by Anne Wernikoff for CalMatters

The Paradise Village developer has asked Rep. Doug LaMalfa, a Republican representing Paradise, and Democratic U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein to lobby the IRS for an extension. Neither LaMalfa nor Feinstein would comment for this story, but the developer said their staffs are exploring what’s possible.

Asked if Gov. Gavin Newsom would try to intervene — or if the war of words between the Newsom administration and President Trump over wildfire and housing issues might complicate this matter — a Newsom spokesman said the governor’s offcice is now aware of the situation and is “actively learning more.” One affordable housing expert said it was unlikely an issue like this would be politicized at the IRS.

State funding may be at stake too. Paradise Village was granted $5 million in low-interst state loans for its initial construction–if the project is not rebuild, the nonprofit developer will be on the hook for repaying that, plus interest.

Rich says if the complex isn’t rebuilt, Paradise will lose an integral part of the community.

“If they only rebuild for people who are homeowners or people with a certain amount of money, she said, “they’re taking a part of Paradise away.”

Why rebuild in Paradise? And won’t this happen again somewhere else?

The developers of Paradise Village say they are frequently contacted by former residents wondering when they can move back.

“Nobody acted better than anybody else there,” said Cindy, who rented there for a year and declined to share her last name, citing privacy concerns. “You didn’t feel like someone was going to put you down because you didn’t make as much money as them.”

Disabled because of a multiple sclerosis diagnosis in 2007, Cindy was one of last residents to evacuate Paradise Village the day of the Camp Fire. She considers herself lucky; one older resident died in the blaze.

But the trauma — she still has nightmares about the fire — doesn’t deter Cindy from wanting to move back. Fires can happen anywhere, she said. “I think that’s just how it’s going to be. The world has changed.”

Officials rebuilding Paradise say they are taking significant steps to mitigate future fire risks: easier exit routes, burying power lines. But the question of whether to rebuild in Paradise at all, and particularly low-income apartments funded by taxpayer dollars that often house disabled residents, persists.

“If we took that approach, that any time you have a fire you need to walk away from it, where would you be building then in California?” asks Zappettini, the nonprofit developer.

There are more than 4,000 low-income housing projects subsidized by the Low Income Housing Tax Credit in California. Most are in urban areas, but many are in rural or exurban parts of the state at higher wildfire risk.

Merritt Community Capital, the investor in Paradise Village, also invested in four low-income projects evacuated due to the ongoing Kincade Fire in Sonoma County. None were damaged.

Zappettini says the federal government should adjust to California’s new normal and grant more time for rebuilds.

“I’m hoping that this changes the nature of the IRS rules so that they contemplate the potential of disasters and needing to be more flexible…to allow these developments to come back,” she said.

If Paradise Village is not rebuilt, Nancy Rich says she’ll probably try to find subsidized housing in Oroville, about half an hour from where she works. She wants to avoid moving in with family for as long as she can — - the homes of her mother, sister, and daughter all burned in the Camp Fire, and she doesn’t want to be a burden.

She’d much prefer to be back in Paradise.

“I miss it. I miss the smell, I miss the altitude,” she said.

“The familiarity and knowing where you can go and what you can do. It’s home. It just felt like home.”

###

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE