For nearly 30 years, Danny Henderson struggled with an addiction to heroin. The drug pulled him so deep within its grasps that he lived on the streets for 16 years — spending his days mostly roaming to find enough recyclables to get enough cash so he could score his next bag of dope. His addiction led him to the some of the shadiest parts of Eureka where he saw young girls strung out and preyed upon by older men. He bought drugs in horrifying situations with stacks of guns and cash sitting next to piles of heroin and meth. His addiction and lifestyle led to him getting stabbed four times in the stomach behind the Bayshore Mall when he was caught by a rival group transporting heroin in Eureka.

But that is in his past now. Henderson — the Outpost is withholding his real name in order to protect his privacy — is currently in treatment at the Waterfront Recovery Services. A decision he made almost flippantly as he was walking to the dump to cash in some of the recyclables he collected the day before. Henderson’s story is uncommon in the sense that he actually got help to kick his addiction — something that is not readily available to all of Eureka’s homeless population.

Waterfront Recovery Services

Waterfront Recovery Services is a treatment facility in Eureka. They focus mainly on helping the impoverished and low-income. Henderson was able to find treatment there because of funding through Measure Z. But, those funds are not a guarantee. Both Waterfront officials and police officers on the front lines of combating addiction fear that the improvements that have been made thus far may begin to reverse due to a loss in funding.

As you walk the streets of Eureka, signs of addictions are all around. In the faces of people asking for money and in the faces of people sleeping on the sidewalks. You can see the signs of addiction in the feces and syringes that mark the sidewalks — both obvious signs of not only addiction, but also a lack of services for those who call the streets home. You can also hear the results of addiction in the conversations that some of our homeless and mentally ill counterparts are having with what appears to be the air.

Addiction is a disease that affects all backgrounds and levels of the socioeconomic ladder. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse,130 Americans die every day from opioid overdoses. It is something they call “a serious national crisis that affects public health as well as social and economic welfare.” NIDA went on to say that 1.7 million Americans struggled with prescription drug abuse in 2017 and 652,000 struggled with a reported heroin use disorder.

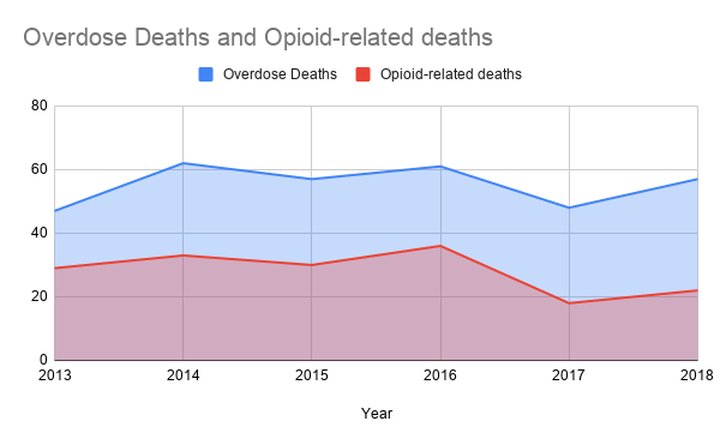

Overdose and Opioid-related deaths

From 2013 to 2018, Humboldt County experienced 332 overdose deaths with 168 of them opioid-related. As of late August, there have been 19 confirmed accidental overdose deaths, according to the Humboldt County Coroner’s office — one case in July and eight in August are pending confirmation from the Coroner’s office. Out of the 19 cases, 14 can be attributed to opioids — this includes everything from prescription drugs to heroin and fentanyl.

Henderson’s path to sobriety involves not only the desire to see change within himself, but also the compassion of others who want to see a better community. A community that is free of the blatant struggle and obvious side-effects of addiction.

Henderson first started using heroin when he was 15 years old. He started getting high off pain pills and wasn’t aware of their addictive qualities until after he was well within their grasp. When those ran out he turned to heroin. He and a buddy first scored some black tar off the streets of Susanville and shot it up.

Off and on throughout his teenage years, he would steal heroin and prescription pills from his parents — both of whom also struggled with an addiction to heroin and only got clean when they were in their 50s.

“We all had some sort of substance abuse problem,” Henderson said. “It seems like it was in the family.”

Henderson joined the military when he was 17 and was stationed in Georgia. His time in the military would be one of the last times Henderson was sober. When he was 20, Henderson bought a motorcycle and took a trip from his father’s house in Susanville to Humboldt. He visited an uncle and planned on picking mushrooms with him.

The trip didn’t last too long, but it gave Henderson a footing into a place that he would visit off and on for the next few years.

Henderson’s heroin use and his ultimate decision to stay in Humboldt would coincide with one another. His first time buying the drug here in Humboldt would prove to be an experience he will never forget.

It was nighttime and Henderson was walking to the Pine Hill Trailer Court on Alpha Street in Eureka. He was scared. An acquaintance had arranged the deal and he had never met the people he was about to buy from. When he opened the door, he saw what he described as a “horrible mess.”

“There were guns and there was a lot of money,” he said. “There were big piles of heroin just sitting there, you know, and piles of speed and people drinking. There was definitely under-age girls that shouldn’t have been there, strung out with older men that shouldn’t have had them there. You know, when that stuff gets under your [skin], it’s all bad. It was an experience that I won’t forget.”

Henderson’s drug use mostly kept him on the streets. He found housing from time to time and eventually met a woman. The two never married but went on to have three kids together. During this time, Henderson and his partner were using drugs as well. He said his partner’s drug of choice was speed.

“She decided that she wanted to go a different route, because she was tired of [using],” Henderson said. “She raised my daughters to be the right way and I broke off from the family and went about my business.”

He continued to use heroin and was eventually arrested for a number of burglaries and theft — all to fuel his addiction. He was never really a part of his children’s lives. He would stop in from time to time to ask for money but never stuck around long enough for them to build a strong relationship. His actions over the years resulted in alienation from his family.

“I stole from my family,” he said, “disappointed my daughters and my grandkids. It’s not been good.”

After leaving behind his family, Henderson called the streets home for almost 20 years. He spent most of his days just walking around, trying to find a warm place to sleep during the day, and spent the nights digging through trash cans. Sleeping during the day time acted as a protection against theft, Henderson said.

He was cold all the time and had to carry extra clothes for the changing weather. He would ditch them whenever they started to get in the way of collecting recyclables. He never had a cart, only trash bags and whatever he could carry in a backpack. He rarely visited the free food services because of his social anxiety. Henderson said he preferred rummaging through the garbage for food and every now and then someone would buy him something to eat.

Audio: How Henderson fed his addiction

His need for heroin kept him wandering, always searching for enough money to get his fix. He said the withdrawals ranged from a runny nose to cold sweats and cramping. He would even throw up and defecate himself if he couldn’t find any heroin.

“You would do anything to get a shot of heroin at that time,” he said. “[You’re] a slave. A slave to the drug. Totally, 100 percent.”

Throughout the years Henderson lost a handful of friends to some of the side-effects of long-term drug use. He lost one friend to hepatitis and four to overdoses in the past 10 years.

“It’s very common for people to overdose in the streets,” he said. “We just never hear about them because, to society, they’re nobody. That’s how I look at it anyway.”

Some past run-ins with the police may have helped contribute to Henderson’s feelings about how society views the homeless. His run-ins have varied, but an encounter at Hammond Park about a year ago with a Eureka cop sticks out in his memory.

“I had one come up to me one time and he said, ‘You know, the reason why I’m hassling you?’ and I said, ‘Probably because I’m using drugs,’” Henderson said. “[The cop] goes, ‘Because I’m tired of piece of shit homeless fuckers like you.’ That’s exactly what he said.”

But the lives of the homeless matter to some, and there are many in the community actively working to change the lives of the people they see struggling. The Eureka Police Department started the Community Safety Enhancement Team on July 1, 2018. One of the main focuses of CSET is to address some of the underlying issues that cause homelessness.

It was June 19 around noon on a sunny day in Eureka and Henderson was strung out on heroin, walking to the Eureka dump when he ran into Sgt. Leonard La France of the Eureka Police Department.

Humboldt Waste Management Authority

“When are you ever going to quit?” Henderson remembers La France asking him. “I’m giving you a chance right now to do that because the next time I see you, you’re probably going to be dead.”

It didn’t take Henderson too long to decide what to do. He handed off some of his supplies to a few friends and left the recycling on the street. He loaded up into the back of La France’s unmarked cop car and was brought straight to Waterfront. Henderson said it was a decision he knew he wanted to make. However, it was also one of the most nerve-racking decisions in his life.

“I’m leaving something behind that I’ve known for so long, which was heroin and the streets, to change my life,” he said. “I’ve been tired of [it] for a long time.”

Henderson was able to access services at Waterfront because of funding through Measure Z, a half-percent countywide sales tax approved by voters in 2014 to pay for maintaining and enhancing services.

Audio: Henderson’s time at Waterfront

Measure Z funds a plethora of services and has myriad benefactors: the Sheriff’s Office, the District Attorney’s Office, Eureka Police Department, Department of Health and Human Services, Orleans Volunteer Fire Department, Waterfront Recovery Services, Arcata Police Department’s Juvenile Diversion Program, KMUD Community Radio’s emergency broadcast system, Eureka City Schools, the Eel River Cleanup Project, road repair in EastHum, WestHum, NorHum and so on and so on.

Glenn Ziemer is the chair of the Measure Z Citizens’ Advisory Committee and represents District 1. He said applications to receive funds through Measure Z go through a ranking process. The committee received over 50 applications for Measure Z funds that will be delegated in 2020 and only 19 applications met the standards necessary for the committee to recommend funding.

The $10.76 million available for Measure Z in 2020 is over $2 million short of the $12.89 million in 2019. Ziemer believes the gap in funding is due to a sales tax shortfall that is linked to the decline of the buying power of the cannabis industry. Ziemer told the Outpost, that the applications are judged on how well they comply with the intent for Measure Z and that they are based “kind of on a cost-benefit analysis.”

Ziemer went on to say that the committee takes into consideration how many people will benefit from the services being proposed in each bid for Measure Z funds as well as the efficacy of the programs. During presentations to the Measure Z committee, Ziemer said some of the recovery service providers took swipes at each other’s work.

“There were some presentations to the committee this year, from certain aspects of the treatment services community alleging certain providers were not cost effective,” Ziemer said. “I found that a little concerning in the sense that I am not a recovery services expert and it’s hard for me to judge Provider A against Provider B based on a fairly short application. The competitive nature meant that there were four or five of the treatment services providers that were not successful in reaching funding this year.”

There are also a few discrepancies with how the funds should be used. When Measure Z was first established, it was done so with the intent that the funds would not be used to establish new positions that rely solely on the Measure Z funds to pay for the position. But as the years have gone by, this intent has gone to the wayside, leaving programs like Waterfront Recovery Services, road repair countywide, and other community programs fighting for the leftover funds. Ziemer said the costs of having to consistently fund personnel positions is “rapid eroding” the funds available for other services.

“This is basically law enforcement people, it’s sheriff’s officers, officers with the various local police agencies, public defenders, people in the district attorney’s office, and those types of positions,” Ziemer said. “We didn’t think it was a good strategy for the community to have to hire 15 deputies one year and lay them off the next year because there was inconsistency in the funding. So although there is no overt guarantee that those positions will be funded, the general sense of the committee and the Board of Supervisors has been that they want the personnel aspects of it to be as stable as they can be.”

The constant need to provide stability and the infighting between between the addiction treatment centers are two of the reasons why Waterfront Recovery Services did not receive Measure Z funds in 2020.

Although they received Measure Z funds the previous year, Waterfront received a 8-1 vote saying their services did not fit within Measure Z’s intended purposes. The lone yes vote was from Nick Kohl, the Fourth District representative on the committee.

“When you have something that says it is a recovery center for the homeless, I see that as a mental health need, but that in and of itself didn’t fulfill the full mental health guideline for Measure Z,” Kohl told the Outpost over a cup of coffee at Old Town Coffee and Chocolates. “It was really disheartening because it made me realize what the priorities were for the rest of the county as a whole.”

According to county data, roughly $4.2 million of the $10.76 million funds are solely funding salaries for positions. Kohl said this is a point of contention among the committee members. He said he wants an itemized list of the positions with the costs associated with each to help provide some clarity on how the money is being spent. The funding of personnel positions is making it harder to not only address the needs of the more urban areas of Humboldt, but also the rural areas as well. The county only allotted $115,750 for Measure Z public works projects.

“For a lot of the rural areas, roads are a big priority,” Kohl said while pointing out that public works projects tend to either be a “backburner issue” or are cut first while labor is usually cut last. “It’s not that I want people to be fired, but I want to see equity in the cuts. There is such a diversity of environment and community, that to get a consensus on this is really hard.”

Kohl’s main focus on the committee is much like the others, advocating and trying to best address the needs of his area. For Kohl, that involves addressing mental health and homelessness in Eureka.

“Treatment is one of the biggest issues I want to see move forward in Eureka,” Kohl said. “My goal is to advocate for my district and to find a sense of community.”

Waterfront has been granted a short reprieve from the worries about Measure Z funding. At the beginning of September, Waterfront and the Department of Health and Human Services signed a contract that provides eight beds at Waterfront for short-term detox purposes — a process that usually takes between three to ten days, said John McManus, executive Director of Waterfront Recovery Services. The contract lasts through March and is aimed at helping “folks in desperate need.”

Henderson said he was nervous about entering treatment at Waterfront. He suffers from a bit of social anxiety. He feared how the staff and other patients were going to treat him. But his fears turned out to be unwarranted. He found a welcoming staff that offered a bed and a shower for the first time since he could remember. He was given clean clothes and food as well as Suboxone — a drug that helps ease the side effects of opiate withdrawal.

But patients can’t receive Suboxone right away; they “pay a little bit,” Henderson said.

He had been wanting to get clean for some time but couldn’t bring himself to do it. He didn’t want to wait around for paperwork to be filled out and for any sort of approval through MediCal. He wanted, as he put it, “instant gratification” and La France was able to make that happen due to Measure Z funding.

In 2019, the Eureka Police Department received $512,840 in Measure Z funds that went towards two officers — a homeless services program manager and a Waterfront ranger — as well as “funding for housing, detox and residential treatment services.”

La France told the Outpost the funding for housing, detox and treatment for this time period was about $83,000, and with those funds EPD was able to redirect 38 people into treatment services at Waterfront.

Since they opened in 2017, Waterfront officials estimate they have helped around 1,200 people. McManus has been working in the addiction treatment industry for 20 years. He first got involved in helping others with addiction after battling it himself.

“I was a heroin addict,” McManus told the Outpost. “I cleaned up and had no intention of working in this type of field, but started doing it. When I was in college, I worked at a residential program as a night supervisor.”

John McManus

Waterfront is significantly different than the treatment program McManus went through. There are meditation rooms and a garden. Patients take part in discussion groups where they try to focus on their underlying issues and there is a focus on nutrition and healthy eating. McManus said the old way of getting clean focused more on the struggle than actually addressing the cause of the addiction.

“Back then, the thought was you would hit bottom and the horror of what you were going through would prevent you from going back to it,” McManus said. “You didn’t get medications. You got bare minimum stuff. You didn’t sleep for weeks. You would throw up. You would shit your pants.”

McManus said they have about a 70 percent success rate at Waterfront — which means that about 70 percent of their patients make it all the way through to a graduation, an event to celebrate the completion of Waterfront’s 30, 60 or 90 day programs. During a graduation, family members are brought in as well as some of the people a patient may have bonded with over their time during the program.

Dr. Ruby Bayan is the medical director at Waterfront. She’s an adult, child and addiction psychiatrist and has nearly four decades’ worth of experience. She is originally from southern California and made her way north about 14 years ago when she took a position at Semper Virens, the County’s short-term mental health facility. It was while working there, that Dr. Bayan realized the shortfall in mental health services here in Humboldt County.

“It’s my life’s mission to take care of the most broken people,” Bayan told the Outpost while on a tour of the Waterfront facilities. “When I came here, this is what I wanted to do. I wanted to [treat] mental health and addiction. However, I realized quickly that there were really no addiction services, from the medical point of view.”

Dr. Ruby Bayan

Bayan estimates that around 80 percent of their patients are homeless and most of them come from broken homes where drug use was quite common. While there are a number of reasons people turn to drugs, officials from Waterfront, EPD, and Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office all said the main cause of addiction tends to be childhood trauma.

Dr. Bayan: “Most of [our patients] come from families where drug use is normal.”

Sergeant La France of EPD: “I think the biggest [predictor] is childhood trauma and that just leads them to a path where they are looking to heal that wound, and self medicate, and just take away that pain. But I’m not really sure about a gateway [drug]. Trauma is probably the biggest cause, and if we look at the bigger picture, trauma in childhood.”

Sergeant Jesse Taylor of the Humboldt County Drug Task Force: “A lot of people who suffered childhood trauma — sexually and physically — are damaged and turn to drugs. For the most part, it is just people who get trapped inside of this game and they don’t want to be there. The heroin addicts are doing it just to get by. Most addicts I talk to hate the lifestyle and want to get out.”

Henderson grew up with absent parents who struggled with their own battles with addiction. They left drugs around that Henderson took and used and eventually became addicted to. Henderson believes his upbringing contributes to his current state of mind.

“I have huge emotional problems and PTSD from being places where I shouldn’t have been,” he said. “And so I use drugs use to cover that up. But I didn’t know that at the time, you know? It was really hard for me to go on with a normal life, because I thought, if I tried to do that, then all this stuff inside of me would come out. And that I wouldn’t be me, you know, who I am on the street.”

Henderson’s story isn’t all that different from many children in Humboldt County today. If you look into services that help children in adverse conditions, there is a significant historical gap. Back in 2015, Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services as well as the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office were sued by the state Attorney General’s Office for not “properly receiving, responding to and investigating reports of child abuse and neglect.”

As recently as Dec. 2018, there were 308 backlogged investigations of child abuse and neglect. Child Welfare Services has also faced a historical lack of staffing and recently hired 40 new employees. CWS brought the backlog of cases down to 63, but given the routine understaffing it seems like a lot of damage has been done.

In a previous interview with the Outpost, CWS Deputy Director Ivy Breen said there are many families in their services who have dealt with generational trauma. Breen went on to say that Humboldt’s rurality and size also contribute to its inability to quickly address reports of child abuse and neglect.

The case load for the CWS workers here in Humboldt is nearly three times the recommended amount. From March 2018 to Feb. 2019 CWS received a total of 3,217 reports of suspected child abuse or neglect. With their current staffing levels at around 90 employees, Breen is hoping to more efficiently address some of these reports.

Henderson was 78 days clean when he spoke with the Outpost. He was spending his free time reading Les Miserables and spoke about how much of a fan he was of Victor Hugo.

“It’s an awesome book, probably one of the best I’ve ever read,” Henderson said from across the table. He was wearing blue jeans and a blue Les Miserables t-shirt with a little girl on the front.

He spoke about how society tends to dismiss addicts, and the need for compassion.

“We, as a society, tend to say ‘if you’re a junkie, you’re on the blacklist, no matter what.’ And that’s not true,” Henderson said. “Everybody’s a human, you know? Everybody is somebody’s kid and everybody is somebody’s sister, you know what I mean?”

He also spoke about the need for reform in the criminal justice system and how simply locking people up isn’t working.

“I think if they put as much money into fucking arresting people and shit like that into drug education then we’d be squared away,” Henderson said. “Education works, throwing people in jail doesn’t work. It creates hatred for the system. It creates huge financial problems.”

The conversation lasted for over an hour. Henderson teared up at times while talking about his past and the struggles he dealt with. But there was always a hint of optimism in his eye and the conversation ended with Henderson excitedly speaking about his job prospects and life after Waterfront.

He plans on going through the outpatient treatment offered by Waterfront at one of their facilities on C Street. While Henderson will have the freedom to move about society as he pleases, there are rules. He said he can’t stay out past 11, can’t have girls over and he must have a job. Henderson is also taking the steps necessary to fulfill one of society’s most basic civic duties, voting.

“My grandma taught me that not knowing enough about a vote is a dangerous vote,” Henderson said. “So I got to really look into what I’m doing.”

Immediately after the interview, Henderson put on a plaid button-up and tidied his hair. He was preparing for two job interviews that afternoon — with Pacific Choice and Danco. With a smile on his face, Henderson stepped into the sunlight outside of Waterfront and headed west — off to new opportunities and a fresh start.

CLICK TO MANAGE