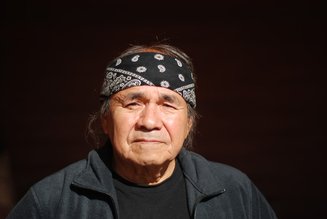

“From Wounded Knee to Standing Rock” features the story of Willard Carlson, a Yurok native from the Klamath River.

Willard Carlson and his friends pulled over for breakfast when they got their first taste of what awaited them and other activists headed to Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in March 1973.

Carlson, a Yurok whose home overlooks Blue Creek, had listened when American Indian Movement leaders Dennis Banks and Russell Means called for supplies, medicine, guns and people as they protested a corrupt Oglala Lakota tribal chairman and stood off against the federal government.

Carlson, his friends Calvin and Alan Aubrey and Russell Redner, and other Humboldt State University students, loaded up a camper and an old Datsun pickup with weapons, ammunition, medicine and camping gear and set out from Arcata.

They reached a restaurant in Chadron, Nebraska, but left without breakfast when they realized it was full of law enforcement. On a deserted dirt road outside town, Carlson and his friends made a difficult decision and embarked on the tensest stretch of their journey.

“We all had to make an agreement, well if we get stopped and the cops pull guns on us, we got to shoot it out. Everybody had to agree to it,” he said. “So, we all agreed to it in this field.”

Carlson is one of the main protagonists in journalist Kevin McKiernan’s film “From Wounded Knee to Standing Rock: A Reporter’s Journey.” The film will be screened at the Eureka Theater on Oct. 19.

Willard Carlson’s journey from Arcata to Wounded Knee in 1973 is featured in Kevin McKiernan’s film, “From Wounded Knee to Standing Rock.” Photo: Jessica Cejnar

The screening will include a discussion with Carlson, his son Pergish Carlson and Jack Norton, an emeritus professor of Native American studies at Humboldt State University. The discussion will focus on activism through the generations.

Humboldt State was rife with student activism in the early 1970s, including involvement from the Black Student Union and the Chicanos on campus, Carlson said. At the time, Native American students closely followed the news from Indian Country. This included AIM’s takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in Washington DC in 1972 and Alcatraz Island in 1968, Carlson said. AIM was their Civil Rights Movement, Carlson said. Then, Wounded Knee happened.

On a sunny Thursday morning over coffee at the Redwood Hotel and Casino in Klamath, Carlson described the violence and corrupt tribal government of Richard A. “Dick” Wilson’s, elected chairman of the Oglala Lakota Sioux of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. There were escalating tensions and misappropriation of funds on the Pine Ridge Reservation, Carlson said. Officials’ families got first crack at housing, the best jobs, better services for elder housing, school and other opportunities, he said.

Wilson’s government had expected AIM to react and outfitted the BIA building with turrets and militaristic-style weapons. Then there was the police presence, Carlson said. Wilson even had his own followers, the Guardians of the Oglala Nation, or GOONs, Carlson said.

Then an Oglala elder decided to make a stand at Wounded Knee, Carlson said.

“It turned into an armed uprising,” he said. “And, being a student and following the news — ‘cause it got national and international media attention — (we said), ‘Wow, this is really happening.’”

Following a quick trip to the Oregon border near O’Brien to get rifles from his mother, Carlson and his friends set out from Arcata. They purchased $80 worth of ammunition from a sport shop in Willow Creek — according to Carlson, the money came from an HSU professor — and found themselves in Sparks, Nevada at 9 p.m.

As they were pumping gas, Carlson said a native man and his wife offered them sandwiches and coffee and to bless them with cedar smoke. The couple told Carlson and his friends that because of possible harassment from the police, they didn’t drive at night. But, Carlson said, he thinks the couple was meant to find him and his friends.

“He blessed us, our courage, strength, spiritual, mental,” Carlson said. “It wasn’t a big o’ drawn out thing. It was very brief. I believe that guy, whoever he was, helped us on our journey because it was a very dangerous time.”

Carlson and his friends found out how dangerous traveling across the U.S. was at that Chadron, Nebraska restaurant. With Carlson behind the wheel, they loaded up their weapons, left the dirt road and found that a state trooper was following them.

A second state trooper got behind them eight or 10 miles down the road. When he backed off, another took his place, Carlson said. Each new jurisdiction brought a new patrol car until they reached the 3-lane highway that led to Rapid City.

“That was the most nervous stretch of how many miles before we got into the main flow of traffic to get to Rapid City,” Carlson said. “When we got into the flow of traffic, that was a big big relief.”

McKiernan was also at the Wounded Knee Uprising. The protest was his first story as a young NPR reporter. He said he and Carlson met in 2011 while he and his wife was trying to find a camping site on Yurok land. Each didn’t believe the other had been there, McKiernan said, until Carlson produced a photograph of himself and other armed Indians. McKiernan was the photographer.

In his film, McKiernan said he focuses on Carlson as part of AIM’s clarion call. Hundreds of federal agents, many who had fought in Vietnam, had surrounded the hamlet of Wounded Knee, McKiernan said. But he noted that many of the protesters had also fought in Vietnam.

“Willard wasn’t in Vietnam, but he was good with guns,” McKiernan said. “I use him also in clips where he’s talking about informers, federal informers, who were in Wounded Knee and how you had to be very careful. And later, I have him talking about almost being shot to death in Wounded Knee.”

In “From Wounded Knee to Standing Rock,” McKiernan tells what reporting on the 1973 uprising was like. Because the government had blocked the press from entering the area to cover it, McKiernan said he had to sneak in.

“I was arrested and charged with two felonies,” he said. “Though they were thrown out later.”

According to McKiernan, Carlson told him the media was the greatest weapon Native Americans had in the 1970s.

On Thursday, Carlson told the Wild Rivers Outpost that the mistreatment of Native Americans on the part of non-native officials occurred on Yurok lands. Sheriff’s deputies and California Department of Fish and Wildlife agents harassed or arrested natives, Carlson said.

He said his mother was arrested for trespassing across Green Diamond and Simpson timber property to access her own lands. This action resulted in the 1981 Blake v. Arnett 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruling that stated natives could pass through private property to access their own land, Carlson said.

Before, Yuroks were told they had to get to their property via helicopter or boat, Carlson said.

“This is just stuff we had to deal with everywhere,” he said, adding that he and Yurok tribal members still experience conflict with state and federal officials. “A lot of change has happened, but these things still exist.”

However, Carlson, who was a non-violent protester of the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock, South Dakota in 2016, said people are increasingly aware that things have to change.

“Native peoples and non-native peoples, we all have to share this planet, to take care and do our part,” he said. “Standing Rock showed how thousands of people can come together.”

“From Wounded Knee to Standing Rock: A Reporter’s Journey” features cinematography from Haskell Wexler and will be screened at the Eureka Theater on Oct. 19. Doors open at 6 p.m. The film starts at 7 p.m.

Tickets are $8 for students and seniors and $12 for general admission and are available at Annex 39 in Eureka or at the door.

From Wounded Knee to Standing Rock - Trailer from Seventh Art Releasing on Vimeo.

CLICK TO MANAGE