Crowds arrive at the Capitol for the 2017 Women’s March. Photo by Jim Heaphy via Creative Commons

As the #MeToo movement against sexual harassment washed across the country last year, it hit especially hard in the California Capitol.

Three lawmakers resigned amid serious allegations of sexual misconduct. The Legislature spent months crafting a new procedure for handling complaints from its employees. And by the end of the legislative session, dozens of bills had been passed to prevent future harassment or help victims seek justice in workplaces across the state.

Then-Gov. Jerry Brown signed many. But in Brown’s typical fashion — what he called paddling left and paddling right — he vetoed other measures, arguing they were unnecessary, hasty or in conflict with federal law.

Now, there’s a new governor in town, and with him, high hopes that Gov. Gavin Newsom will reward the persistence of those whose harassment bills were rejected by Brown.

Among the roughly 700 bills on Newsom’s desk are several inspired by the #MeToo movement, including many repeats of bills Brown vetoed last year. Others are new ideas or rehashes of measures that stalled last year before reaching the governor’s desk — such as a bill prohibiting settlements that say an employer will never again hire an aggrieved worker.

The most controversial #MeToo bills will force Newsom to decide between two constituencies that are important to him: On one side, powerful business interests that argue the measures will increase costs and litigation. On the other, feminist and worker advocates who say progress shouldn’t slow just because public outcry about harassment has dimmed.

“It was an important year to show that we weren’t going to drop this issue or imply that it was somehow fixed. We made some progress last year but there is a lot of work still to be done,” said attorney Jessica Stender of Equal Rights Advocates, which sponsored some of the bills on Newsom’s desk, including two that Brown vetoed last year.

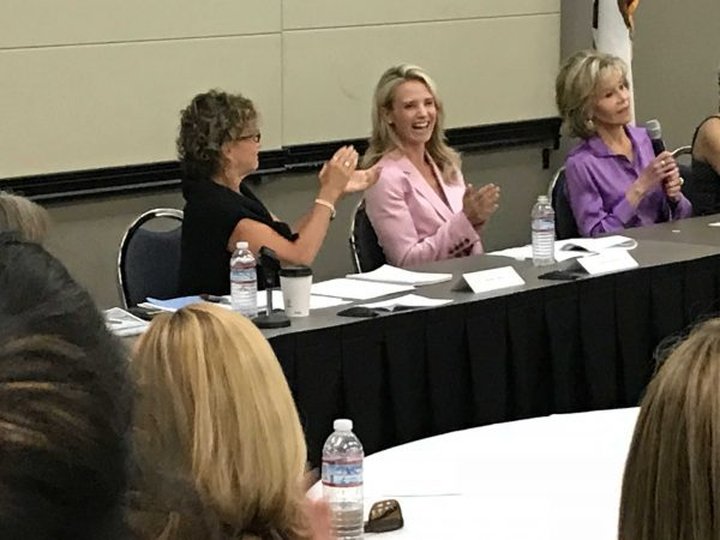

Jennifer Siebel Newsom, center, and actor Jane Fonda, right, were among the advocates for a vetoed mandatory arbitration bill that has was reintroduced. Photo for CalMatters by Dan Morain

“Having these bills reintroduced this year was an important statement.”

Her group is backing Assembly Bill 9, which would give workers two more years to file harassment and discrimination claims, and Assembly Bill 51, which would prohibit employers from requiring people they’re hiring to agree to resolve disputes in private arbitration, instead of through the courts.

Supporters say many harassment victims who work in low-wage jobs need more time to file claims because they may not immediately realize that what happened to them is illegal. And they say requiring that disputes go to private arbitration puts workers at a disadvantage and allows misconduct to stay secret.

Brown vetoed similar versions of both bills last year, saying the current statute of limitations encourages employers to resolve problems swiftly and that the move to ban mandatory arbitration clauses violates federal law. With his vetoes, Brown sided with the California Chamber of Commerce and numerous other business groups who say the proposals would lead to more litigation, and therefore greater costs for employers.

“There are a lot of legitimate and concrete reasons he vetoed a lot of these bills,” said Jennifer Barrera, a lobbyist for the California Chamber of Commerce. “It had nothing to do with his lack of sensitivity to the #MeToo movement, but either the law already exists and we don’t need it, or (it would create more) liability and litigation.”

Newsom has already shown that he wants to distinguish himself from Brown. He announced plans to scale back his predecessor’s legacy projects to build massive water tunnels through the Delta and a high-speed rail line from the Bay Area to Los Angeles. He approved temporary tax breaks on diapers and menstrual products that Brown rejected. And he signed a bill Brown vetoed that requires presidential candidates to release their tax returns if they want to be placed on the California primary ballot. (It was recently put on hold by the courts.)

Nate Ballard, a political consultant who worked for Newsom as San Francisco mayor, said he expects Newsom will differentiate himself from Brown on the #MeToo bills as well.

“There’s a pretty good chance those bills are going to get signed,” he said.

In part he chalked it up to a generational difference between the 51-year-old Newsom and 81-year-old Brown that may make the younger governor more attuned to issues women face in the workplace. But he also attributed a lot of influence to Newsom’s wife — a filmmaker whose work focuses on gender inequity.

Before Newsom was elected, Jennifer Siebel Newsom lobbied in favor of last year’s version of the arbitration bill. She hasn’t been publicly involved in campaigning for this year’s version but has used her high-profile position to advance other feminist causes, such as equal pay.

“Jennifer Siebel Newsom is a feminist activist who is engaged in these issues every single day of her life,” said Ballard, who sits on the board of Siebel Newsom’s gender equity nonprofit. “That brings a valuable perspective into the governor’s orbit that most male governors just don’t have. She is up to her ears in feminist activism and that makes a difference.”

###

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE