Roger Boulby stood atop the steel treads of the hydraulic excavator he’d just driven across a shallow stretch of the Trinity River, all 88,000-pounds of machinery rumbling beneath his work boots as he reflected on the job he’s been on for the past several months.

That job, known as the Chapman Ranch Project, is part of the largest environmental restoration program ever implemented on the Trinity, and it’s being led by his own people, the Yurok Tribe.

Roger Boulby, watershed restorationist and Yurok Tribe member.

“This is all super-gratifying work,” Bouldy said, looking around at the newly reshaped landscape. He’s a watershed restorationist with the Yurok Tribe and an expert with the excavator.

Over the past several months, Bouldy and the rest of the all-Native American construction crew — half Yurok, half Hoopa Valley Tribe — transformed a roughly 1,000-yard stretch of the Trinity near Junction City from a brisk straightaway that barreled through a mostly lifeless expanse of rock into a meandering riverbed complete with new side channels, wetlands and large wood features.

“Basically, our goal out here is to make it more fish-friendly instead of like a bowling alley,” Boulby said. He’s been doing restoration work for more than two decades, and he said the results are almost immediate.

“You see every year when we’re done, the fish start coming and start spawning in places where there was no spawning ground. So, like, we created that channel over here,” he said, gesturing toward a gentle backwater. “As soon as I dug this out there were 30 salmon. They went right in there.”

Funding for the $4 million Chapman Ranch Project comes from the Bureau of Reclamation via the Trinity River Restoration Program (TRRP), a multi-agency effort established in 2000 with the objective of restoring fisheries impacted by dam construction and related diversions.

Historically, the Trinity, the largest tributary of the Klamath River, hosted thriving populations of steelhead, coho and Chinook salmon, which provided local tribes with their primary dietary staple since time immemorial.

It wasn’t just the dam that altered this waterway. Mining activities in the 19th and 20th centuries drastically changed the river’s character and its capacity to support wildlife. For more than 100 years — from the early days of the Gold Rush into the 1950s — zealous gold hunters employed hydraulic mining, blasting the river canyon with high-powered water cannons to release the gold-bearing placer gravels, and in the process they washed hundreds of millions of cubic yards of debris into the river valleys of the northern Sierra Nevada.

Hydraulic mining at the La Grange mine — once the largest of its kind in the world — on the Trinity River, circa 1870. | Public domain.

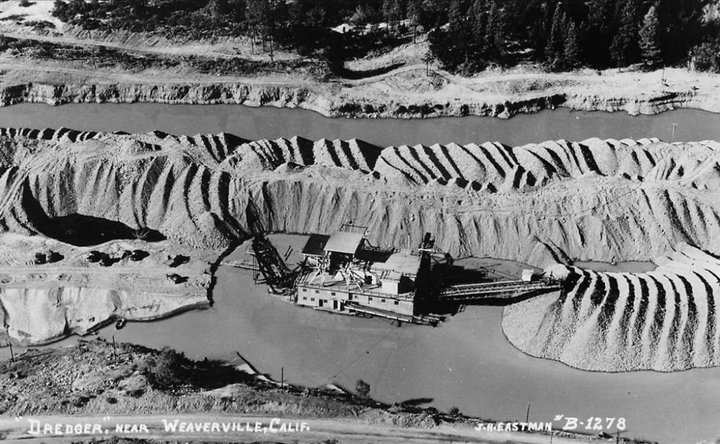

This technique was followed (and sometimes accompanied) by the use of industrial dredges, massive extraction machines that suctioned the precious metal from the rock and gravel now spread thick in the river valley. As shown in the photo below, these hydraulic dredges left huge tailings in their wake — peaked ridges of lifeless rock that can still be seen on the banks of the Trinity.

Dredger mining on the Trinity left behind tailings that line the river to this day. | Public domain.

“And right after the dredgers stopped, they put in a dam and turned off the water,” said Aaron Martin, the lead fisheries biologist on the Chapman Ranch Project. The dam took the muscle out of the river, he explained. “So it’s totally stuck. This channel has not migrated or moved anywhere in, like, 20, 30 years.”

Dave Gaeuman, lead geomorphologist on the project, agreed. “The channels through this part of the river are just basically these ditches that are 15 feet deep into all this mining debris that was washed off the mountainside,” he said.

The TRRP is intended to restore the upper Trinity to some semblance of the thriving and dynamic waterway that once existed here. Each year, work crews take on new restoration projects along the 40-mile stretch from the Lewiston Dam to the North Fork.

Chapman Ranch will be the 33rd site completed out of 47 locations identified for “mechanical restoration” on the upper Trinity, according to TRRP Executive Director Mike Dixon. These restoration projects have been growing steadily more complex and sophisticated over the years. Other aspects of the TRRP include fish passage work, road sediment reduction and restoration of various tributaries.

Last week, the Outpost toured the Chapman Ranch site with several of the people who’ve led the project, including Martin, Gaeuman, Project Engineer DJ Bandrowski and Restoration Specialist Eric Wiseman.

Project Engineer DJ Bandrowski describes the Chapman Ranch River Restoration Project onsite.

In a briefing before the tour, Bandrowski described the big picture, explaining that what had essentially been a long ditch in the mining rubble was transformed in part by lowering the floodplain and building a series of three “meander complexes” — S-curves that will move around over time as the river washes away sediment from some areas and deposits it in others.

Sections where the main stem used to run, meanwhile, were converted into side-channel habitat, calm waters that will function as juvenile rearing areas. Mid-channel islands were built and large wood features were incorporated into the riverbed to create wildlife habitat, direct water flow and stabilize the landscape.

However, it’s not supposed to remain static. Bandrowski describes these river restoration projects as catalysts for change. “We set it up and put in a condition where the river can respond from there,” he said. “If you come back three years from now and it looks the same, then we’ve failed. We’ve done something wrong. We built a static system.”

As we walked from the staging area down toward the river, Bandrowski said that as the complexity of these restoration projects has advanced over the past five years, so too have the Yurok and Hoopa tribes’ capacity to implement the projects. The Chapman Ranch Project is the first instance where the construction crew is 100 percent native.

“So every operator out here — every single laborer, every single technician — is a tribal member,” he said. And members of the two tribes coalesce into a cohesive unit. “Hoopa and Yurok have a lot of differences at the higher level, in the political arena, but operationally? That’s gone. There’s no drama out here, no issues.”

As the lead fisheries biologist, Martin said monitoring projects, including adult fish surveys and rotary screw traps to count juveniles, show that the restoration work is working. “We’re making more juvenile fish get to the ocean,” he said.

The goal, he said, is to have 60,000 naturally produced fall Chinook, the size of runs before the dam was constructed. Current numbers are highly variable, but a big year, according to Martin, is between 5,000 and 30,000. “We’re nowhere close to our goals,” he said. But the restoration work is having an effect.

Standing at the water’s edge, Gaeuman explained that part of the restoration involves depositing gravel upriver. “Those dams obviously stop all the gravel that would be coming in from the upper basins,” he said. “So we add gravel just so the river will have material, like this stuff here, that the water can move around. You can build a bar over there, the bar here gets eroded and it keeps rejuvenating all the habitat.”

The meander complexes, little islands and side channels provide a stark contrast to the ditch-like conditions of this stretch before work began. And with the floodplain lowered along the banks, the landscape will continue to change when the rainy season arrives.

Gaeuman pointed to various features in the river as he spoke. ”So now this water is going to be all over this whole area during higher flows, providing a lot more habitat, and at low flows it’s splitting around this little bar, this island, so you’ve got this little eddy here [and] the fast water’s over here. So there’s a lot of diversity of habitat.”

While we were standing on the gravelly bank we saw some sudden movement as a creature of some sort scurried under one of the root wads in the bank and disappeared from view.

“What was that?” Bandrowski asked. Gaeuman was closest. As he and others moved in for a closer look, the critter sprinted from beneath the root cluster, running right between Gauman’s legs before swimming across the mouth of a side channel. It scampered up the far bank and hid behind a log.

The critter in flight.

When given a vague description of the animal later that afternoon, Boulby guessed it was probably a juvenile marten. [Note: Reader Phil Johnston identified it as a mink, based on this photo.] “Yeah, he’s been around; we’ve seen him,” Boulby said. “There’s eagles here, there’s bears here, deer. It’s pretty cool. The eagles come right down and land, scope us out.”

Standing on his excavator tread he imitated an eagle soaring in the sky. “When the eagles fly over and they hang out and watch us, to us it’s like a blessing, like we’re doing good,” he said.

These restoration projects are designed to provide even more habitat for the local animal species. After all the trucks and tractors leave — the “yellow equipment,” as Bandrowski called it — workers move into the replanting phase. That work was already under way last week.

“Everything gets used,” Bandrowski said, “from blackberry slash to wood chips, it becomes floodplain wood.” All this organic material provides “micro-hydraulic complexity … so [water] just doesn’t sheet across here at high velocities.”

One example of this revegetation work could be seen on a nearby peninsula, where arced rows of willow sticks emerged from the rubble at a high angle, looking like giant eyelashes.

A willow trench.

Bandrowski explained that workers harvest pole cuttings and soak them in back-channel waters for two weeks before the revegetation crew sets them into a trench.

“Sometimes we put a punky alder or a rotten piece of wood into the trench to help retain moisture, help it to grow,” he said. “Then we water the shit out of ‘em for the summer.”

At the base of the pole cuttings, new green growth was emerging. This will grow up into a willow forest eventually,” Bandrowski said. In the meantime it will direct river flows while gathering and depositing fine sediment.

A root wad exposed on the river bank. “We sharpen the tips of the wood and drive it horizontally with the excavator into the bank so we’re not disturbing the root mass,” Bandrowski said.

“The wood is really that carbon addition that’s crucial,” Wiseman explained. “It’s carbon, the building blocks of life. … The systems in the whole western United States are sterile; there’s hardly any nutrients in ‘em.”

He gestured toward some of the mining tailings nearby. “This was a dead, lifeless zone,” he said. The ridged piles of rock could get up to 170 degrees. “Nothing could survive, not even a lizard,” Wiseman said.

A special strain of native straw that allows seeds to germinate has now been spread along the floodplain in the reformed river basin. Growth has already begun, and the landscape looks a bit different each day.

Boulby operates an excavator as a water truck crosses the river.

In a phone conversation on Tuesday, Dixon said the TRRP has now accumulated three decades or more of monitoring data, and the results were recently compiled into some synthesis reports that reveal what’s been accomplished and what needs to change.

The reports are just now entering the peer-review process, so they’re considered preliminary, but Dixon said that since restoration-level water flows were implemented in 2005 the program has roughly doubled the mean number of juvenile Chinook salmon that leave the Trinity for the Klamath each year.

What’s more, for every adult salmon pair that spawns in the Trinity, more of their young are making it out thanks to habitat restoration and flow management.

“We’ve given the river so much more room, doubling to quintupling the amount of habitat, depending on flows,” Dixon said.

Future projects will be even more complex than the Chapman Ranch Project, and with budget cuts — there was a 20 percent reduction in funding to the TRRP for the upcoming fiscal year — the whole restoration program isn’t expected to be complete until somewhere around 2032.

“The asterisk I like to put on when we talk about time scales is that it took nearly 200 years to mess the Trinity up as it is right now,” Dixon said.

Little by little this restoration work is making the Trinity look more like it did centuries ago.

“This is, like, instant gratification,” Boulby said.

Judging by the results, the fish seem to agree.

CLICK TO MANAGE