Five months in, and, as a nation, we’re still floundering: 4 percent of the world’s population with 22 percent of the world’s Covid deaths. For comparison, Japan, with 40 percent of our population, has experienced less than 1 percent the number of our C-19 fatalities. They’re fortunate in that they don’t have our ’Murica-Land-of-the-Free mentality. Having survived SARS and MERS, the Japanese are used to wearing masks, distancing, and all the rest. So where are we at now?

Fifth Coronavirus?

SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for Covid-19, is a coronavirus, one of seven known to infect humans. Two of these — the original SARS virus (2002-2004) and MERS (2012+) — are much less infectious than the present coronavirus. The other four (229E, OC43, NL63 and HKU1) cause most cases of the common cold. The most likely endgame, according to many researchers, is that SARS-CoV-2 will become the “fifth coronavirus,” regularly circulating among us, but in a milder and less lethal form.

This makes sense: a dead host is no use to a virus. To survive, it needs live hosts, walking around, infecting other people. So long-term, we can expect this virus to mutate into, so to speak, a kinder, gentler form.

Vaccine?

A Covid vaccine probably won’t be the magic bullet we’re all hoping for: it’s unlikely that the first approved vaccine will be final “best” one, plus, once a vaccine is certified for universal use, we’ll probably need to get it annually, like a flu shot.

Because C-19 isn’t going to go away, ever. Currently, while we have vaccines for about a dozen human viruses, only one virus-caused disease — smallpox — has been totally eradicated. And that took nearly 20 years of intense and unflagging international cooperation and vaccination: a far cry from today’s competitive, nationalistic atmosphere.

Masks?

Although usually promoted as protecting others, a cloth mask also helps you, the wearer, by limiting the “viral load” you might inhale when you’re around someone who’s infected. Researchers are pretty sure that, if you are infected, the smaller the load the less serious your symptoms. It’s unclear just how many C-19 viral particles it takes to infect someone (SARS took a few hundred while the critical dose for MERS was several thousand), but if 1,000 Covid viruses land you in hospital fighting for your life, 500 might only make you feel lousy for a few days. (And that 500 difference could be from wearing a mask.)

This was the case with chickenpox, before a vaccine was released in 1995. “It’s the second child in the home that gets much sicker, because they’re exposed to much more [chickenpox] virus,” according to vaccine expert Dr. Paul Offit. Same with the hepatitis B virus: the greater your viral load, the sicker you get.

Immune Systems?

Our immune systems have (very roughly) two main lines of defense against viruses: antibodies, i.e. proteins that recognize distinctive parts of the virus (epitopes) and then essentially smother it; and killer T-cells, i.e. cells that recognize epitopes on the surface of a virus-infected cell and instruct the cell to self-destruct. Typically, antibodies and T-cells go hand-in-hand during epidemics, so if someone displays antibodies (which are quick and easy to detect from a blood sample) they also have T-cells (which can only be detected with specialized lab tests).

SARS-Co-2 appears to be an exception to the “antibodies and killer T-cells work in tandem” rule. For instance, one study found that two-thirds of asymptomatic close contacts of an infected person had abundant T-cells but no detectable antibodies. Just one more challenge as scientists try to understand this oddball virus!

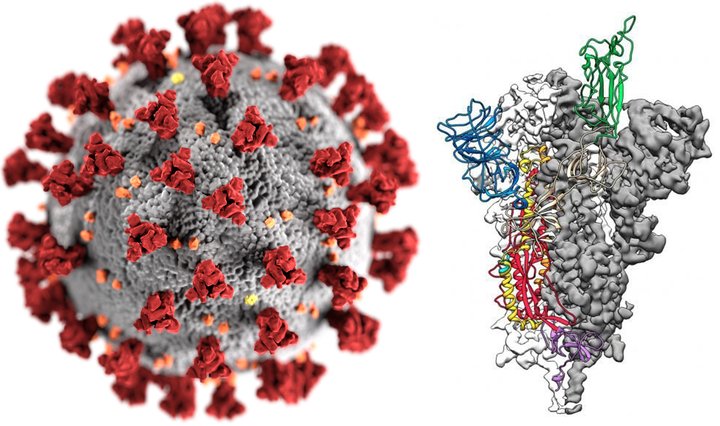

Left: Single Covid virus (1/100,000th the size of a grain of salt) with red “spikes.” (CDC) Right: Spike detail. The spikes on the surface of the SARS-CoV-2 virus may act as epitopes to be recognized by a potential vaccine. Each spike is an elegant assemblage of three identical protein chains (protomers), two of which (white and gray) are illustrated without detail, while the third is colored according to the different domains in the protein. (Jason McLellan, University of Texas at Austin, used with permission)

###

SARS-CoV-2 really is novel, and researchers have only six months of data to go on. In that time, however, they’ve figured out a lot about it, including: its RNA genome; its probable source; how it gets transmitted; and what types of vaccines can be used against it. (Currently over 160 candidate vaccines are in development.) Every week produces new data and new surprises. In a year we’ll know a lot more. Until then, you know the protocol: masks, hand-washing, six feet … and avoid gatherings (“super-spreaders” have morphed into “super-events”).

Unless your idea of a good time is having a ventilator shoved down your throat.

CLICK TO MANAGE