Photos: Ryan Burns.

Former Humboldt County resident Suzanne Sevier McBride recently commissioned a new bench for the Myrtle Grove Cemetery to provide seating for cemetery volunteers, to recognize her pioneer ancestors Aristides (A.J.) and Annis Huestis and to honor Silva, a Native American woman who was legally indentured to A.J. Huestis in 1861 and represents an important reminder of Humboldt’s painful past.

McBride learned about Silva in 1998 after she received a box of discarded family photos from the Eureka Police Department. In the collection, McBride found two identical photos of a Native American woman and through diligent research eventually identified her as Silva, a young woman legally bound to the Huestis family in 1861 under the 1850 “Act for the Government and Protection of Indians.”

The law allowed for the legal indenture of Native Americans under a variety of circumstances, and allowed “masters” to secure “… care, custody, control, and earnings” of a Native child until he or she obtained the age of majority — 18 years old for males and 15 for females. Under the original law, Native children could be indentured only if the justice of the peace was convinced that no compulsory means was used to obtain the child, but in 1860 the law was expanded to allow for the indenture of prisoners of war. It also extended the terms of indenture. In 1860, boys under 14 could be indentured until they were 25 and girls until they were 21. Children over 14 could be indentured until they were 30 and 25 respectively.

During the “Indian wars” of Northern California, many men and women were indentured under this law, but the majority were children, likely because they were easier to control and less likely to escape their masters. Boys and girls as young as four or five were tasked with childcare and household chores and children as young as seven or eight were put to work in the fields. Demand for these young servants grew and Humboldt County became infamous in the trafficking of Indian children. Traffickers would raid Native villages, often killing the adult inhabitants, and then gather up and sell the children for $50 to $250 each. By August of 1857, the Humboldt Times newspaper was reporting regularly on the practice, asserting that a many Indian parents had been “shot down in cold blood” and the inhuman practice of kidnapping was “going on with the steadiness of a regular system.”

Huestis, serving as a Humboldt County Judge in the 1860s, signed the orders on many local indentures, and also had 14-year-old Silva bound to him on March 5, 1861. According to the original indenture record, Indians on their way to the Klamath Reservation had offered to sell the orphaned Silva to Huestis for $20. Huestis refused to pay for the girl but did offer to let her stay. According to Silva’s obituary, she ran away within days but was captured and returned to Huestis. At that time, when given a choice between staying with the family and being sent to the Klamath reservation, where Native inhabitants faced abuse and starvation, Silva chose to remain.

And there she stayed, even after the Thirteenth Amendment was passed in December of 1865, making slavery and indentured servitude — except for those duly convicted of a crime — illegal. After the death of Judge Huestis, Mrs. Huestis and Silva moved in with Huestis’s daughter, Mrs. Nathaniel Bullock and it was in their home that Silva died of tuberculosis in 1893.

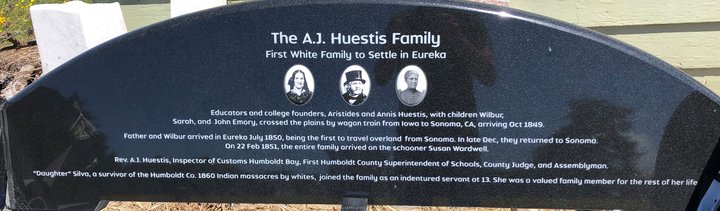

The text on the bench. Click for detail.

“I really wanted to honor her,” Suzanne McBride explained recently when asked why she included Silva’s photo on the memorial bench. “She was in a home of educators so they would have taught her to read and write (this is true according to the 1870 Federal Census) but she was with the family the rest of her life. She never married or had a chance to have a family of her own. She could have left, but I’m not sure how. If she could have found a place….”

McBride prefers to believe that Silva was treated like a member of the family, and the Silva’s studio portrait supports the possibility, though Silva’s obituary described her as a “faithful servant and companion.” The obituary also describes her as kind, honest and “of good impulses.” Silva, it added, died a Christian.

“I just wanted to do something to help us remember what the indigenous people went through,” McBride explained. “I just wanted to acknowledge her and her people somehow…” While the bench features photos of Huestis, his wife and Silva, Suzanne did not include photos of the Huestis children because “they didn’t count in this regard.” McBride wanted the focus on Silva.

For more

information on this history of kidnapping and indenture in Northern

California, see “Masters, Apprentices, and Kidnappers: Indian Servitude and Slave Trafficking in Humboldt County, California, 1860–1863,” by Michael F. Magliari.

###

Lynette Mullen writes about Humboldt County history at Lynette’s NorCal History Blog. On Tuesday, Aug. 11, she will teach an online course for OLLI entitled “Enslaved in Humboldt: The Story of Caroline Wright.” Click the link for details.

###

CLICK TO MANAGE