We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which were not to be seen as superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which the Maya regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction.

— Diego de Landa Calderón

###

At sunrise on July 12, 1562, the Maya people of what is now Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula possessed an extensive cultural history in the form of dozens — perhaps hundreds — of handwritten books. By nightfall, virtually all that heritage was gone, devoured in the flames of an auto-da-fé ritual supervised by Franciscan friar Diego de Landa Calderón. By his own account, 27 books, or codices, were burned, although historians suspect his claim is a vast underestimate. All that are left today are three Mayan codices, with perhaps parts of a fourth (historians debate its authenticity), which somehow escaped Landa’s fanaticism.

No one, as far as we know, died that day. No massacre, no torture (although Landa was known to have used torture extensively, particularly on Mayan nobility), no physical abuse. Just the books, and thousands of figurines, died. But, because each of these was unique in its own way, whole chapters in the history of a people were lost. Much of what we do know about the Maya comes from the remaining codices, such as the “Dresden Codex,” the oldest book we have from the Americas, dating back to approximately 1200 AD (300 years before the Spanish conquest). Like the other two (or three) surviving Mayan codices, it’s written on amate, the inner bark of the wild fig tree, and is folded, accordion-style. Opened out, it’s about 12 feet long, 8 inches high, written on both sides. Only recently fully deciphered, it consists of astronomical data (particularly of the planet Venus, which the Mayans associated with warfare) and a listing of ceremonial events.

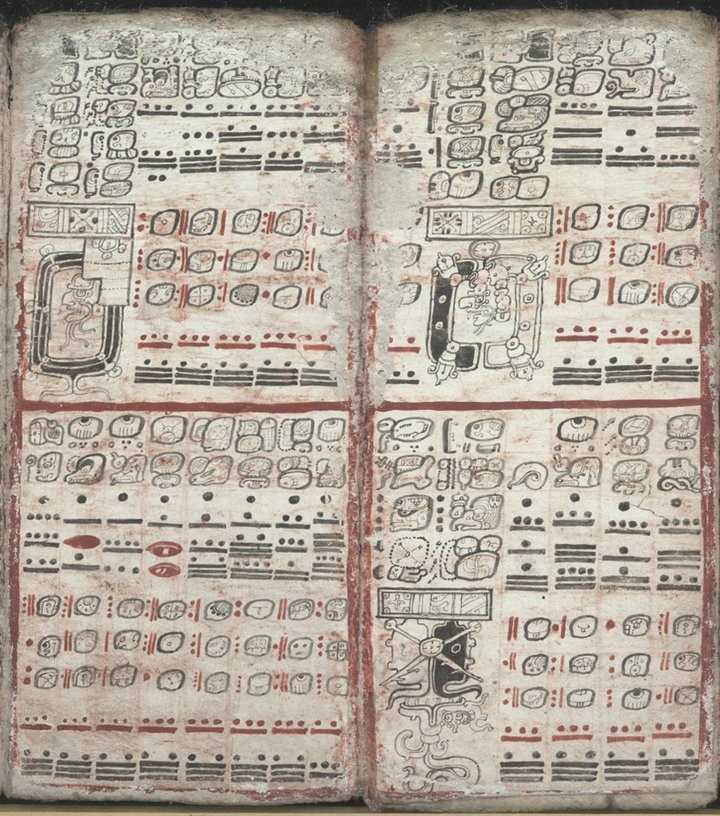

Two pages (of 78 in total) from the Dresden Codex, recording lunar eclipses. (Wikimedia)

So why did Landa pursue his crusade against what he perceived as idolatry — he also burned thousands of cult images — with such vehemence? According to historians who study the era, he thought — in common with most other Franciscans of the time — that the Second Coming was nigh (perhaps at the turn of the century), and it was his duty to save as many souls as possible. Which, of course, meant eliminating what he saw as pagan practices and cult worship. Hence the destruction of books containing “nothing in which were not seen and superstition and lies of the devil.”

The Maya were the most advanced people of the New World. In addition to writing, they built hundreds of stone temples, pyramids and palaces. Their irrigation works were as sophisticated as any in the Old World. Their calendar was astonishingly precise, starting with a creation date of August 11, 3114 BC, cycling every 18,980 days (i.e. about a lifetime, 52 years). Their astronomical records allowed them to figure out the synodic period of Venus as 584 days — it’s actually about 583.92. And their civilization lasted for over 1,000 years. If you’re interested, I wrote about theories of their demise here.

Author at Calakmul in the south of Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula, pretending to understand the glyphs on a 1200-year-old stela.

Ironically, we have to thank Landa for preserving much of our knowledge about the Maya people who lived at the same time as his 16th century Yucatán crusade. Landa had two Mayan scribes show him how to read their hieroglyphics (kind of — a Soviet linguist showed in the 1950s that many of his conclusions were inaccurate) and his account of pre-conquest Mayan social organization has been invaluable to future historians. Still, for me, and apparently for the contemporary descendants of the Mayan people (judging by this mural in Mérida’s Governor’s Palace), Landa was and always will be an asshole.

CLICK TO MANAGE