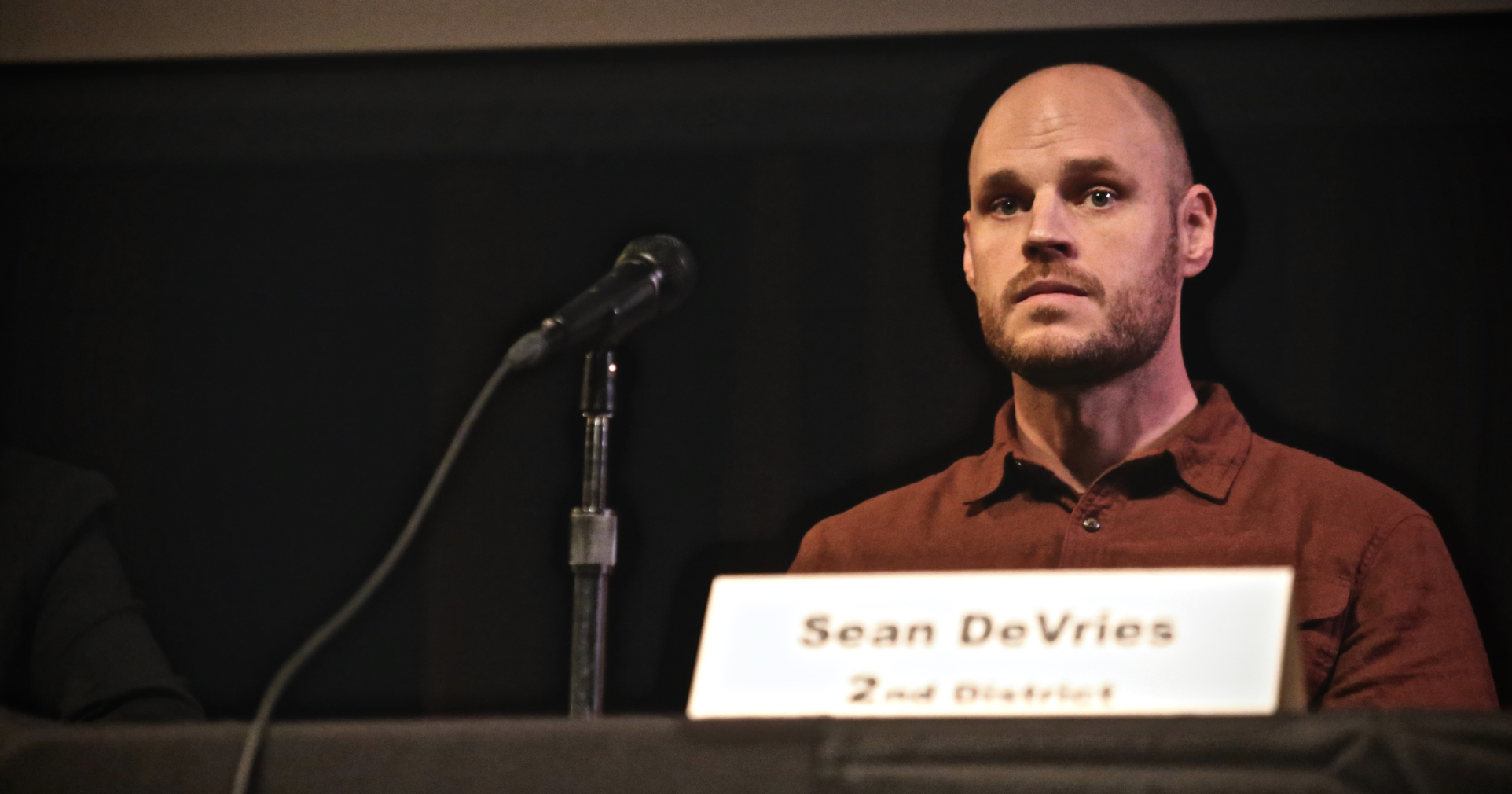

Candidate DeVries at a recent forum | Photo: Andrew Goff

# # #

Sean DeVries, one of five candidates running for the Second District seat on the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors, has seen the rumors being posted about him online. There’s the one about his company soliciting mortgage loans in New Hampshire without a license (totally baseless, he says); the one about his involvement in the Florida Tea Party (true but misunderstood); and the ones about his litigious dealings in the San Francisco cannabis dispensary business.

“I’ve had an interesting and complicated past because the things I’ve been involved with have been politically charged,” he told the Outpost in a recent phone interview. “I’ve been in battles, and I’ve got some scars, apparently.”

We asked him to explain some of the turbulent chapters of his recent past, and though he was periodically vexed by the scrutiny and concerned about the potential impacts to his campaign, he proved more than willing to discuss the issues and share information. He forwarded legal filings, web links and old emails, and he offered lengthy descriptions of his labyrinthine business dealings.

Over the years, he said, he’s poked a few bears, and they’ve fought back. He’s been burned by unscrupulous business partners, victimized by outright frauds, targeted for retribution by both the Republican Party of Florida and the City of San Francisco, and attacked with “hit piece” journalism — all because of his efforts to challenge authority, expose corruption and fight for the little guy, he told the Outpost.

Below we look at three chapters in his past, starting with his involvement with the Florida Tea Party.

# # #

DeVries wanted to be absolutely clear that this wasn’t the Tea Party as people generally think of it. This was a scrappy independent chapter, “a party formed by a pot-smoking Democratic attorney and an ousted Republican operative, prior to the knowledge that [the Tea Party] was just a front for the Koch brothers,” he said.

Unlike the broad nationwide movement, the Tea Party of Florida qualified as an official party, and in 2010 DeVries was part of a group that organized a slate of candidates to run for almost every state seat available.

“I was close to the top, involved in writing their 10 points,” he said, referring to the party’s campaign platform. A few days later he backpedaled, though, saying he mainly helped party leaders take the bigotry out of their list of goals (“something about immigration,” he explained) and arranged a spot for them to throw a Fourth of July party.

“My focus was fiscal transparency,” he said. DeVries was living in central Florida at the time, working in the mortgage servicing industry in the wake of the economic collapse of 2008. He was angered by President Barack Obama “bailing out the banks,” and a friend suggested he get involved with politics. He found Tea Party activists on Craigslist.

“When I met with them initially there were definitely a bunch of bigots, for sure,” he said, “not in the main group, just some who came to the rallies.” He encouraged organizers to focus on “smaller government, honesty, fiscal responsibility and transparency,” he said.

The Florida Tea Party wound up causing quite a stir in 2010, angering sitting Republicans and prompting lawsuits over who had rights to the Tea Party name.

“We ran 28 candidates; every single one was sued for fraud,” DeVries said. That includes his own father, John DeVries, who ran for a seat in the Florida House of Representatives after being recruited by his son. (John DeVries wound up getting just 6.39 percent of the vote.)

Republicans sued because they suspected Tea Party candidates of being wolves in sheep’s clothing — or rather Democrats and independents in Revolutionary War garb hoping to unseat true conservatives in the state legislature.

His dad was convicted of violating Florida election statutes after bouncing a check from his campaign account. According to the ruling, the senior DeVries wrote a check for $1,781.82 to the Florida Division of Elections to cover his qualifying fee, but there was no money in the account.

“It was a bullshit thing,” DeVries said, a technicality that was pounced on for the sake of political retribution. “The GOP controlled the Board of Elections,” he said.

But his own motives were genuine, he said. Asked whether his politics as a Tea Party member were different than those he has now, as a candidate for Humboldt County supervisor, DeVries said, “Not really,” adding that his goal, then and now, was honesty and fiscal transparency.

“I was trying to make a difference, just like I am now,” he said. “I got smacked back hard by the system.”

Reprisal came in the form of lawsuits and a “hit piece” about him in the Orlando Sentinel, he said, and he even faced intimidation on the street. “I had dude come up to me in the middle of Orlando. He said, ‘Look at this gun I just bought.’” DeVries said the man pulled out a handgun, showed it to him and then simply walked away, which DeVries interpreted as a threat.

If it was a threat, it worked. DeVries soon left Orlando to attend the Burning Man festival, where he met a girl, and shortly thereafter the two moved to Los Angeles.

Because he was living in California, he said, he didn’t receive a series of registered letters from the New Hampshire Banking Department, including a cease and desist order that accused his former mortgage servicing company, Re-Financial Servicing, Inc., of operating in New Hampshire without a license.

# # #

That cease and desist order is one of the documents that’s been shared anonymously in online comment sections this election season. (It’s posted on the state’s website.)

Dated October 2, 2012, the order says that a man named Christopher Maguire had been offering loan modification services to consumers in New Hampshire while claiming to be an employee of Re-Financial Servicing, Inc.

That was DeVries’s company, registered in Florida with him as president and his dad as vice-president. (Re-Financial was “administratively dissolved” in 2011 for failing to file an annual report.)

The trouble from the State of New Hampshire’s perspective was that nobody connected to Re-Financial — not Maguire, not DeVries, not his dad, nor even the company itself — was licensed to offer mortgages there. In fact, the order says that the Nationwide Mortgage Licensing System & Registry (NMLS) didn’t indicate that Re-Financial or DeVries had ever held a license as a mortgage broker or mortgage loan originator anywhere.

The New Hampshire Banking Department made numerous attempts to reach DeVries, sending certified letters and a fax to Re-Financial’s business address in Winter Park, a suburb of Orlando.

The state says DeVries received at least one of these letters, as well as the fax, but he told the Outpost he’d already left the state by that point, and it’s likely that another tenants in the office building signed for the letter.

Regardless, six months after the cease and desist order, New Hampshire’s then-bank commissioner, Glenn A. Perlow, issued a default judgment against Sean DeVries, John DeVries, Christopher Maguire and Re-Financial Servicing, Inc., fining them $10,000.

Reached by phone last month, New Hampshire Bank Commissioner Gerald H. “Jerry” Little, said the fine was never paid. “Nobody showed, nobody responded, so a default judgment was found against them,” he said.

DeVries said the whole mess was caused by Christopher Maguire, the man originally caught soliciting mortgage business without a license in New Hampshire. “I don’t know who that guy is,” DeVries said.

Based on what he’s gathered after the fact, DeVries believes Maguire was a simply a fraudster who, for unknown reasons, tossed out Re-Financial’s name when he got busted. DeVries said he was completely unaware of the both the cease and desist order and the default judgment until about two years ago, when he was working with an attorney here in Humboldt County.

In March of 2018 he tried to clear up the matter by sending a sworn statement to the New Hampshire Banking Department. (He forwarded a copy to the Outpost; read it here.) It says Re-Financial never hired anyone named Christopher Maguire and never did business outside of Florida.

It lists some of DeVries’s accomplishments as a law student and consumer advocate, and it concludes, “I fight for the little guy. I am the little guy. Please help me resolve this, if possible. I swear to the above under the penalty of perjury.”

A hearings examiner with the New Hampshire Banking Department responded, “Thank you. However, this affidavit is neither signed nor notarized. Please provide a signed, notarized affidavit and supporting documentation of your claims.”

The Outpost asked DeVries via email if he’d ever done so, and on Feb. 7 he replied:

I am now noticing that I did not notarize that declaration.

Which would explain why I never heard anything back…

I will have this notarized and resent on Monday.

DeVries emailed the Outpost an update yesterday: “Spoke with Banking and they are going to be reviewing everything this week, barring any craziness on their end.”

Whether or not the State of New Hampshire absolves DeVries, the Outpost did find evidence that Christopher Maguire was an accomplished and audacious fraudster: In 2015, a Christopher Maguire was arrested in New Hampshire and indicted in Florida on 21 counts of wire fraud, illegal monetary transactions and transporting illegal funds across state lines. He wound up pleading guilty to running a $13.4 million Ponzi scheme.

“The NH thing is identity theft,” DeVries reiterated in an email on Tuesday. “I’d be grateful if that’s how you reference it, if at all.”

But what about the allegation that DeVries never held his mortgage broker’s license? DeVries acknowledged that he did not, but nor was it required in Florida at the time. What he held was simply a mortgage license, aka a real estate license, “as it was required after a certain point to help people fight foreclosure, due to the large number of scammers out there.”

Asked if he had any proof of that license he responded, “I don’t have anything from Florida any longer.” But as supporting evidence of that license, DeVries forwarded a 2009 email from Compliance Consulting Mortgage School, a company in Lake Worth, Fla., that has since gone out of business. “How else would I be on the list for continuing education for mortgage licensees?” he said in an email to the Outpost.

While DeVries has described himself as “the little guy” helping other little guys fight foreclosure, an archived screenshot of Re-Financial’s website from 2010 strikes a different tone. There he describes himself as an expert in underwriting and loan origination and says that the “proven strategy” he developed “enabled Re-Financial to claim $280 million dollars of successful workouts in 2009.” (A loan workout is a plan to restructure debt when facing foreclosure.)

Is that figure accurate?

“If that’s what it says,” DeVries responded.

The $280 million figure is especially impressive considering that Re-Financial wasn’t registered with the Florida Secretary of State until September 3, 2009, meaning it was in business for less than a third of that year.

“I was working independently before I incorporated,” DeVries said, adding that it’s difficult to remember all the details. “Honestly, it was over a decade ago.”

Did DeVries use the Re-Financial name while working independently? “I don’t know if I had used that name,” he responded.

DeVries said he “briefly” held a real estate license in Massachusetts and wrote loans under others broker licenses in three states. He said the reason he wasn’t listed in the NMLS is because registration in the system was not yet required when he was in the industry.

# # #

DeVries’s business dealings in San Francisco are far too complex to fully untangle in this space.

“There’s a lot here,” DeVries acknowledged. “A real lot.” His summation of events was this: “I was burned. I sued my ex-[business]-partner for a bunch of illegal stuff.”

Here’s a slightly longer overview of events based on DeVries’s statements to the Outpost: Around 2015, he entered into a cannabis business partnership with a former tech industry guy named Sean Killen. It was a partnership that would end in acrimony, accusations and lawsuits.

At the time, Killen needed help running a cannabis store in the Bernal Heights neighborhood, so DeVries stepped in, removed an operator who’d embezzled millions of dollars and dramatically increased sales during the six months he ran the place.

DeVries and Killen formed a nonprofit called The New Bernal Heights, Inc. and applied for a new facility down the street, but Killen abruptly ended the partnership.

“He told me I was out,” DeVries said. “He called. It was a two-minute phone call.”

Why did Killen kick him out? “It was just greed,” DeVries said. “He wanted everything for himself.”

DeVries was tight with his landlords and managed to get Killen evicted from the building. He also hired a lawyer and sued Killen for burning his business partners and stealing the organization’s funds.

Killen turned around and sued DeVries, via a new corporate entity, alleging fraud, negligence, wrongful eviction and unfair business practices, among other accusations. Their legal duel has dragged on for years.

DeVries and another business partner, Brett Todoroff, formed a company, HBSF, Inc., and applied to open a dispensary, but their application was rejected by the San Francisco Department of Public Health because “false documentation was knowingly provided to DPH in regards to who the property owner was in a lease,” officials told the San Francisco Chronicle in another story that DeVries considers a “hit piece.”

“I did not commit fraud,” he insisted. As in Florida, this was a technicality that allowed his enemies to exact retribution. He said the city’s public health department hates his guts and blacklisted him from getting a permit because he’d filed an anonymous whistleblower report that outlined a widespread practice of illegal cannabis retail permit transfers. His whistleblower report prompted audits by both San Francisco County and the State of California, he said. (Asked if he could provide a copy of the report, DeVries said he didn’t have one.)

The technicality was this: He and his partner were in the process of purchasing a building for their dispensary and listed themselves as owners — based on a recommendation from a city employee, he said — but they hadn’t taken ownership yet.

DeVries said Killen helped kill his new business venture in part by flirting with a city official to gain her favor. (Killen could not be reached for comment.) DeVries said he caught an opposing attorney lying three times and that the city violated the California Public Records Act by refusing to provide documents he’d requested.

“I’m within my rights to sue the City and force [the release of] those documents,” he said. But hiring an attorney would cost $10,000, and a lawsuit probably wouldn’t get him his permit, he said, “so I didn’t bother.”

There are more ins and outs to this saga — lawsuits, non-disclosure agreements, landlord disputes. “It ruined my life for a minute,” DeVries said. “I had to move away from my son.”

Someday, he said, he’d like to write a book about it.

# # #

Note: This post has been updated to correct the name of DeVries and Todoroff’s business entity, HBSF, Inc.

CLICK TO MANAGE