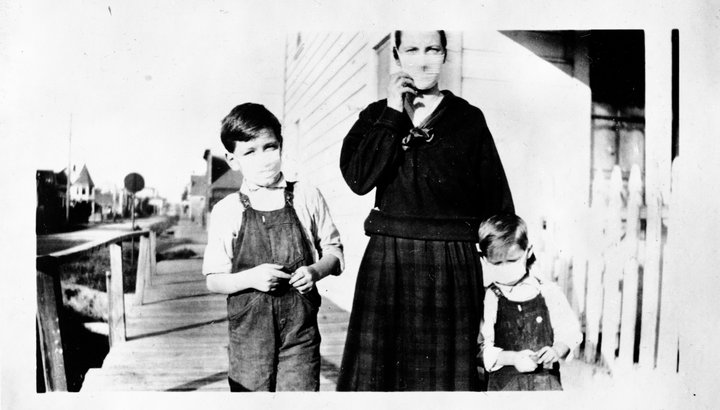

An adult and two children in flu masks. Photo: HSU special collections.

###

PREVIOUSLY:

###

In the fall of 1918, as cases of Spanish Influenza started to rise across the country and in Humboldt County, health officials recognized the virulence of the disease and how gatherings of even a few people could feed an exponential spread. In mid-October, the U.S. Public Health Service cautioned:

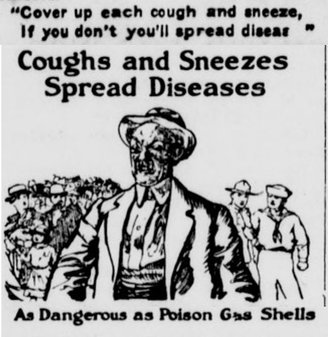

It is now believed that influenza Is always spread from person to person, the germs being carried with the air along with the very small droplets of mucus, expelled by coughing or sneezing, forceful talking, and the like by one who already has the germs of the disease. They may also he carried about in the air in the form of dust coming from dried mucus, from coughing and sneezing, or from careless people who spit on the floor or on the sidewalk.

By the end of October, the State Board of Health would warn that simply by talking, an infected person spread invisible droplets that could give the virus to anyone located within four feet. Coughing increased that radius to 10 feet. Wearing a mask, advice often repeated in the months to come, offered the “greatest service in preventing the spread of the disease.” Those who fell ill were urged to isolate themselves immediately to avoid dangerous complications. Perhaps most importantly, the agency warned that “As in most other catching diseases, a person who has only a mild attack of the disease himself may give a very severe attack to others.”

###

As local case counts continued to rise in Eureka and the surrounding communities, local medical providers voiced concern about their ability to adequately respond to the crisis. On October 19, Humboldt had its first flu-related fatality, reported on page 12 of the Humboldt Times. Victor Tonini, a longshoreman and member of the Italian Order of Druids, left a wife and five children, the oldest 11 years “and the youngest but three months of age.” The same day, the Eureka Board of Health closed all public meeting places, including theaters, fraternal orders, clubs, and dances, prohibiting public meetings and other “assemblages of people.”

Three days later, after over 150 people were diagnosed with the “flu” in Eureka alone, including many nurses and two physicians. Eureka’s officials heeded the State Board of Heath’s advice and ordered “all persons serving the public” to wear influenza masks to slow the spread of the virus. Humboldt County’s Board of Health followed suite, ordering that every person employed in a store, hotel, restaurant, hospital, streetcar, saloon or “in any way waiting upon or serving the public” wear a mask. The order added, “If in doubt as to whether this means you, wear one.” The mask could be simple folds of gauze or cheese cloth. and tied to cover the month and nose completely. Initially people were advised to keep the mask damp with a disinfectant, but that recommendation did not last.

The downtown streets were washed down to dispel any dust that might carry the disease. Many lumber camps, like that owned by William Carson, where men shared close quarters, were closed and fumigated though at least one camp manager took a different approach. According to Matina Kilkenny in her story “Missing Faces,” Carl Munther, superintendent of the California Barrel Company’s McKinleyville camp, kept his camp running and workers healthy by quarantining each employee as they returned from town. Upon arriving back to camp, workers were required to stay for four days in a tent set up away from the workers’ cabins. This policy discouraged workers from leaving in the first place and it kept the disease at bay, with not a single case recorded at the camp during the epidemic.

On October 23, Dr. Wing, Eureka’s Health Official, reported 182 new influenza cases in a single day, up from 125 new cases the day before but still insisted the illness could “soon run its way out” IF [emphasis added] all directions and precautions of the Board of Health were followed. Volunteers set about making anti-flu masks “as rapidly as scissors, fingers and sewing machines could be made to operate” but many still refused to use them, asserting that they had no fear of the disease.

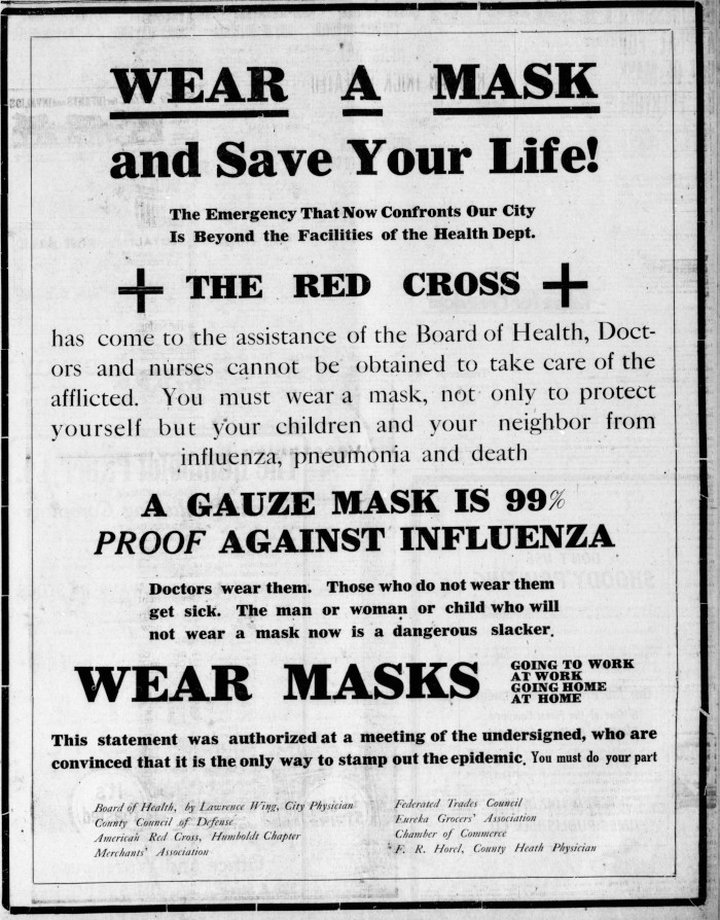

Local businessmen did, if only for the impact on their bottom line. In desperation, they paid for a full-page newspaper ad and made posters imploring the community to wear masks to keep the city’s business interests from being “paralyzed.” The ad seemed to work, as the next day the Humboldt Times reported a “veritable bread line” for masks. Streets, alleyways, homes and businesses were also ordered to be cleaned regularly to stop the spread of germs.

Ad in The Humboldt Times, October 24, 1918.

Despite increasing case counts, at least ten deaths and drastic closures in the community, the editor of the Humboldt Times encouraged the community to “keep smiling”, reassuring readers that the world would not “be turned into a howling wilderness” because of the epidemic, as long as people avoided crowds and wore masks. Even if they thought it unnecessary, the editor admonished, they should wear them “to set an example for others whose lives may be saved by It.” The editorial also prescribed “copious doses of common sense… well digested.” After all, he observed, common sense never did any harm.

On October 25, the County Council of Defense issued “drastic orders”, enforced by the police, that closed non-essential businesses in Eureka and required residents and visitors to wear masks. Smokers, who were used to pulling masks aside to enjoy their habit, would not be excused.

Unfortunately, the country was now fighting two wars, one against the virus and the other against the “Huns”. The new demand for masks diverted 500 yards of gauze marked for surgical dressings for the war front in a single day and to save the precious material, citizens were encouraged to boil and reuse their masks or make them at home using handkerchiefs or other “sanitary” material. Instructions on mask making “so easy, even a child could do it” were included in multiple papers.

The Humboldt Times, Blue Lake Advocate and others now regularly reminded readers that masks were “the best preventative in other cities” and within days of the orders, Dr. Wing proclaimed that the worst of the disease was over, thanks in large part by wide use of masks.

“Coughs and Sneezes Spread Diseases.” Blue Lake Advocate, October 19, 1918.

But compliance was far from universal. Non-masked arrivals to Eureka, many from the mills and shipyards across the bay and accustomed to dropping into a saloon on their way from the boat for a drink or two before going home, were escorted by officers to the nearest drug store to purchase masks. Others received warnings. On October 28, 1918, Ole Olsen was arrested for refusing to pull the mask under his chin up over his nose and mouth and Jesus Lopez was booked for refusing to wear one at all. Lopez was the first “mask slacker” to be fined, and his $5 was forwarded to the Red Cross. Other “mask slackers” were required to “buy themselves a mask”, the price/fine varying depending on the amount they had in their possession.

At the end of October, Arcata followed Eureka’s lead by closing public places and required masks in public and on November 5, at a special meeting, the County Board of Supervisors passed a new ordinance requiring masks and authorizing a maximum penalty of $25 and up to 10 days in the county jail for violators. The city of Eureka passed a similar ordinance shortly thereafter.

On November 2, officials in San Francisco were declaring the epidemic under control and some county officials proclaimed the same, explaining that deaths were still increasing only because the epidemic was running “the end of its course”. Local physicians, like Dr. C. Mercer, then bedridden with the disease, disagreed, blaming the “stubbornness of the epidemic” on the “laxity prevailing among many citizens with respect to the wearing of anti-flu masks.”

Unfortunately, Mercer was right. On November 7, San Francisco reported seventy-three new cases, up 23 from the day before and 48 deaths. Local reports included 78 new cases in two days and one fatality. The Board of Health again emphasized the necessity of “taking every precaution possible, especially the wearing of masks, and the avoidance of crowds, whether indoors or out.” Violators risked arrest and fines, but some, like Gunder Christiansen, arrested twice for wearing his mask under his chin, still stubbornly resisted the order. On November 9, at least 22 people were arrested and fined for similar offenses in Eureka and on November 11, following celebrations dedicated to the end of the war, another 40 were arrested, most of the them drunk. Another arrested was Florence Ottmer, a well-respected local doctor, who apparently wore a mask in public from then on.

Sheriff Redmon and his deputies toured the county’s smaller communities to answer questions and encourage compliance, but some, including residents of Alderpoint, disputed their authority. In response, the local District Attorney assured them that “the quickest and surest way of ascertaining the validity of the ordinance is to appear without a mask, be placed under arrest by the constable, hire an attorney and plead the case.”

In Eureka, though, things were shifting, likely in part from pressure from businesses feeling the economic impact of reduced hours and/or shuttered doors. On November 16, the city of Eureka’s Board of Health pulled the trigger, allowing businesses to resume as normal, as long as people did not congregate and masks were consistently worn. On November 17, with no deaths reported in two days and a continued decline in new cases, the Humboldt Times happily reported that Eureka was “taking on a more lifelike and uplifted air” with more people on the streets and increased traffic in the business district. Perhaps, the editor surmised, the epidemic was at last controlled, and soon the city would return to “a normal condition of life and pleasure.”

While schools remained closed, starting November 19, saloons that prevented crowds could again extend their hours a and ice cream parlors and theaters could open the following Saturday. Dances were allowed to resume on November 24 but permission was rescinded on November 28 after the health board warned that, ” that in a crowded dance hall, in a hot and perspiring condition, the danger of contagion would be at its height, and probably result in another outbreak.”

Dr. Wing continued to reassure the community that the epidemic was played out and the current fatalities were a “normal condition” after such a crisis. He suggested that mask restrictions be discarded within a five-block radius of Eureka’s business district (perhaps as Eureka’s health official he was responding to political pressure?). At the stroke of midnight on November 28, the mask order was rescinded. Fortuna also proclaimed the flu bug “captured” and celebrated with a large gathering in front of the Star Hotel but other communities continued to battle the virus and as residents would soon discover, the crisis was not over….

###

Next Week:

The medical response to the Spanish Flu, including a plea for volunteers, setting up satellite hospitals, the death of healthcare workers and more.

###

Lynette Mullen writes about Humboldt County history at Lynette’s NorCal History Blog.

CLICK TO MANAGE