Sweeney Todd: And what type of form are you in Mrs. Lovett?

Mrs. Lovett: In firkytoodling form Mr. Todd!

My wife introduced me to the old verb firkytoodle which she encountered in a long-ago column by William “somewhat to the right of Attila the Hun” Safire, whose “fuck’em” political outlook was tempered by his love of language. So firkytoodle: while in the 17th century the word meant merely to “fondle,” by Victorian times it had become what the above quote coitally implies.

Sadly, to my mind, we’ve lost many evocative euphemisms for sex, sex parts and sex play over the last century-and-a-half. Whatever happened to “engagement,” “joining giblets,” “knocking,” “prigging,” “tupping” and “wapping”? How come we use so few words for lady-parts these days, when the Victorians had “cloven inlet,” “cock lane,” “cunny,” “madge,” “purse,” “Altar of Venus,” “thatched cottage” and oodles more. Similarly for penis—why use one word when you could choose from dozens more? (Pintle, pillicok, prick, pusher, dresser, pouting stick, horny pipe, linkie-pinkie, fiddle, spindle, bushwhacker, cranny-hunter, Captain Standish, John Thomas…you get the idea.)

Not that the Victorians invented colorful words for sex, of course. The irrepressible Samuel Pepys, whose diary of his years 1660 to 1669, while giving us first hand accounts of the 1666 bubonic plague (which killed a quarter of the population of London) and the Great Fire of London, includes details of his philandering. The entry for October 25, 1668 recounts, “my wife, coming up suddenly, did find me imbracing the girl … and endeed, I was with my main in her cunny.” (Sadly, “the girl” was kicked out while he was allowed to stay.)

Samuel Pepys at age 33, portrait by John Hayls. (Public domain)

A few decades earlier, Shakespeare had been euphemising about sex in just about every play and poem. Venus and Adonis: “Graze on my lips, and if those hills be dry/Stray lower, where the pleasant fountains lie.” Hamlet’s “country matters” has had schoolkids sniggering over the play’s double entendres for centuries:

Hamlet: Lady, shall I lie in your lap?

Ophelia: No, my lord.

Hamlet: I mean my head upon your lap.

Ophelia: Aye, my lord.

Hamlet: Or did you think I meant country matters?

Speaking of which, there’s Chaucer’s use of “queint” on numerous occasions in The Canterbury Tales. In Middle English, “queint” meant “a clever or curious device or ornament,” which Chaucer uses as a euphemistic pun. His much-married Wife of Bath, recounting how she lectured one of her unfortunate husbands who had the temerity to complain about something: “For, certeyn, olde dotard, by youre leve, Ye shul have quente right ynogh at eve.” (Don’t worry, mate, you’ll have me later.)

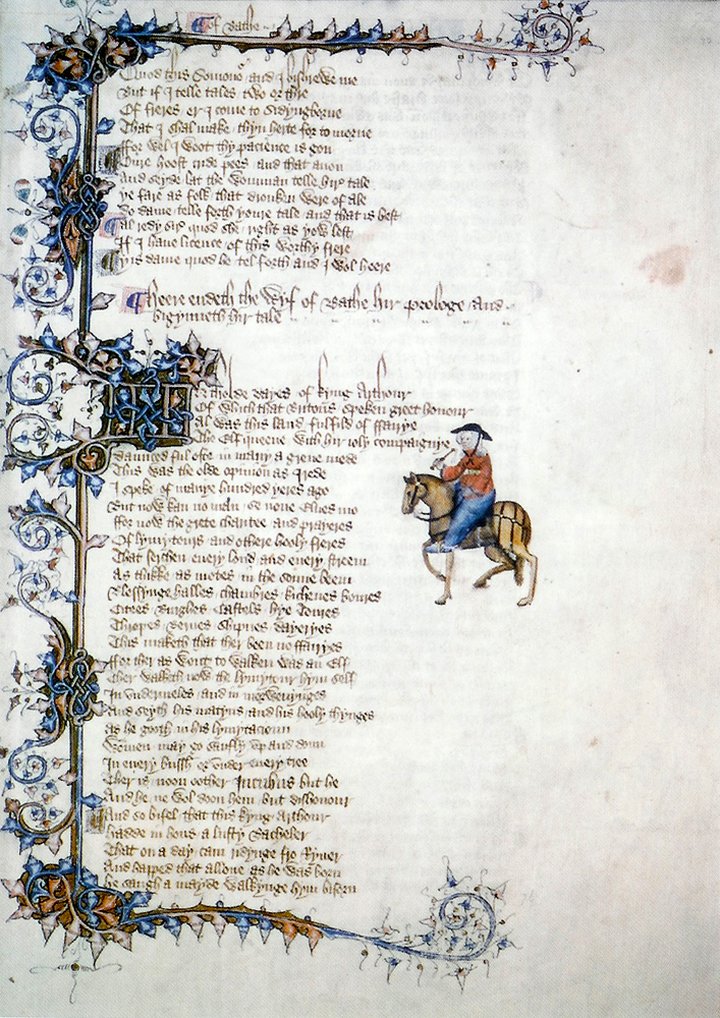

Opening page of The Canterbury Tales from 1410 manuscript. (Public domain)

So yeah, we’ve lost a lot of colorful language in the last few hundred years. Meanwhile the urban legends fly, given new impetus by the ’net. No, there’s no truth in that you had to have the king’s permission to bang away, that is, Fornication Under Consent of the King. Not even the Irish (why is it always Irish?) police blotter notation, “booked For Unlawful Carnal Knowledge.”

No, that sad old word (probably from Dutch fokken, to breed), heard daily—hourly!—from our Old Town apartment is so overused, so trite, banal, uninspired…I could go on. I am so ready for some new ways of speaking about what’s essentially the most natural thing in the world—or maybe going back to good old firkytoodle? We could do worse.

CLICK TO MANAGE