Two students — Haylee (left) and TeMaia — doing an art project in the Del Norte Indian Education Center After School Program at Crescent Elk Middle School. Photo by Angela Davis

###

Working on the North Coast, where the American Civil Liberties Union has had an ongoing presence since 2007, when it filed a landmark class-action lawsuit against Del Norte Unified School District on behalf of Native American students, Tedde Simon says she came to see there was what she described as a “widely understood issue.”

In Humboldt County — home to seven federally recognized tribes and proportionately one of the largest Native populations in the state — Native students were experiencing dismal educational outcomes and it was no secret, says Simon, an investigator and acting Indigenous justice program manager at the ACLU Foundation of Northern California. Rather, she says, it was “widely understood” that local Native students were far less likely to meet basic educational benchmarks and far more likely to be suspended, expelled or suffer chronic absenteeism.

So when the ACLU complied “Failing Grades,” a scathing report on the state of North Coast education for Native youth that was released Oct. 27 and is partly aimed at creating the first citable, published report documenting the problem, she said the findings weren’t exactly surprising.

“It really highlights the incredibly egregious disparities that exist especially for Native kids,” Simon says. “We knew, of course, that this is an issue. Some of this data is not surprising but still entirely shocking.”

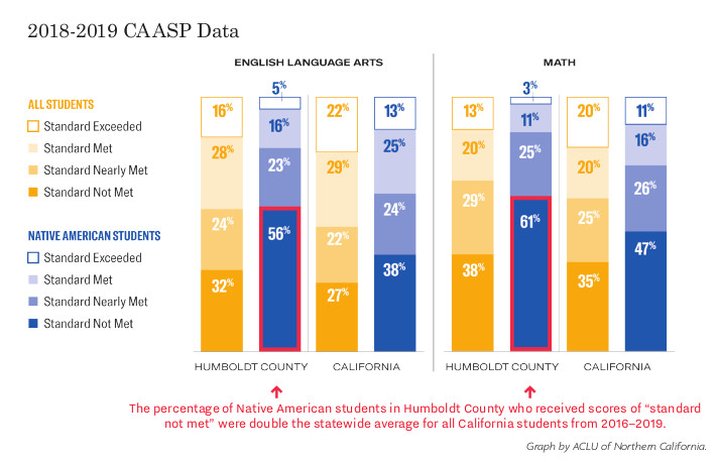

Consider this: In the 2018-2019 school year, 20.7 percent of Native students locally met or exceeded state English language arts standards for their grade levels, compared to 44.6 percent of students overall. The math numbers were even worse, with just 14.5 percent of Native students meeting or exceeding standards compared to 32.5 percent of all Humboldt County students. The report also notes that these outcomes are far out of step with the state as a whole, where an average of 38.2 percent of Native students meet or exceed grade level language arts standards and 26 percent meet or exceed math standards.

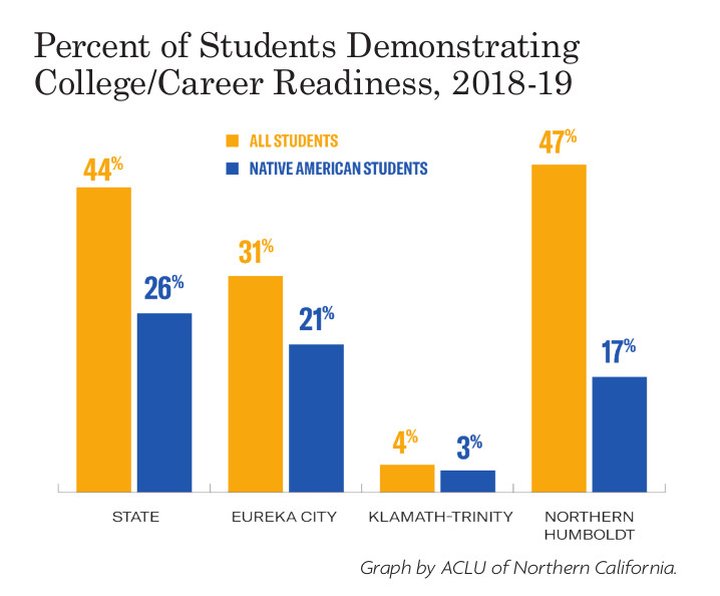

Of all Humboldt County high school graduates from 2016 through 2019, an average of 29 percent left high school each year meeting all entrance requirements for University of California or California State University schools, but only 8 percent of Native graduates met the benchmarks.

The report also found Native students — who make up about 9 percent of local K-12 enrollment — far more likely to be suspended from school or chronically absent than either the general Humboldt County student body or other Native students in California.

Looking through the data, Humboldt State University Native American Studies Chair Cutcha Risling Baldy, herself a product of Humboldt County Schools, says the ACLU’s report is vitally important.

“It’s not that it’s shocking to me, it’s more that it’s validating of an experience we feel,” she says. “We feel this experience. I do think your story and your feeling about it are just as important as the statistics, but to see these statistics all compiled in one place is to see it as a systemic pattern. This isn’t a singular issue, a singular family’s problem. I think it’s important for our youth and our families to see, ‘I’m not alone in this.’ This is a systemic problem.”

But while it may be easy for some to read this report as a “condemnation” of local school districts “because it’s so egregious,” Simon says she and her colleagues used the last two chapters of the report to detail 11 tangible recommendations and a host of resources available to local districts, wanting it to be a “call to action for everyone.”

“It’s not as though school administrators or teachers or people at the district or county level want these outcomes,” she says. “We all know these are issues. It’s impossible to argue that now, looking at all the data in one place. But this is an opportunity to come together and really talk about what can work and what is working in some places, and how that can be adapted and scaled.”

The very first lines of the ACLU’s report paint these gross discrepancies in educational outcomes as a direct result of first contact and the enduring legacy of the slavery and an attempted genocide of Native people in California.

“Since time immemorial, tribes have passed down their cultures, languages and traditions through Indigenous ways of learning and knowing; holistic learning through direct engagement with rivers, forests and the natural world, through oral histories, with the participation of entire tribal communities,” the report’s executive summary begins. “Education has always been key to Indigenous ways of life. But with the first contact between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, public education became a tool of oppression.”

Simon says it was imperative that the report start there and go on to detail how beginning in the 19th century and lasting for generations, Native youth were forcibly taken from their families, communities and tribes to be sent to boarding schools designed to strip them of their language, culture and worldviews. This was Native peoples’ introduction to schools and it came amid other policies that promoted the killing, enslavement and marginalization of their people as ancestral lands were taken from them by force.

When talking about disparate educational outcomes today, Simon says they take root in that context.

“None of these things exist in a vacuum and when we’re talking about Indigenous issues, it all relates back to first contact,” she says. “The public education system was designed to erase Indigenous people. It was designed as a tool of colonization, oppression and genocide. It’s really critical and there’s no way to talk about inequity in the system without talking about how it was designed to erase them.”

And school curriculums continue to erase Native people, says Baldy, who is of Hupa, Yurok and Karuk descent, a member of the Hoopa Valley Tribe and grew up on the coast. Growing up, Baldy says the only times she recalls there being culturally relevant teaching about Native people in her classroom was when her mother and grandmother — or other students’ relatives — stepped in to provide it. And a generation later, with a kid in high school and another in junior high, Baldy says she’s seeing curriculums haven’t changed much.

“It’s pretty standard to what I think people learn in the school system about Native people, talking about us in the past,” she says. “We’re history but not part of the present. We’re only talked about in certain time periods and in certain ways — the mission system was good for us, the Gold Rush was good for progress — but then our people just kind of disappeared (from the curriculum). And they never really tell what was actually happening in those systems.”

In the case of the mission system — often taught as a vital period in shaping California — Baldy says it’s frequently introduced in fourth grade curriculum, which generally minimizes or omits the facts the missions were designed to strip Native people of their religions and promoted their systematic oppression and enslavement.

“People worry, ‘How are we supposed to teach that in the fourth grade?’” Baldy says. “But you know who grows up knowing the truth about the mission system? Native kids.”

So when teachers say they’re protecting young students from this information, Baldy says they’re really just protecting a group — non-Native students — from it while perpetuating a myth and sending the message that Native people’s experiences don’t matter. In contrast, Baldy says an honest teaching of the mission system that “acknowledges the amount of horrific violence” it depended on would reinforce that Native people are powerful and resilient.

But a culturally relevant curriculum goes way beyond history, says Rain Marshall, the Indigenous education advocate for the Northern California Indian Development Council, and should strive to include local Native culture in everything from physical education and nutrition to environmental sciences and storytelling.

“Teachers, I feel, have a professional responsibility to learn the true history of where they live,” Marshall says. “If I went to France to go teach, I would definitely learn a lot about the French culture. Here, I think that’s being ignored. Those cultures are here and vibrant, and all you have to do is ask and you can get that information to share with your students. I feel like the curriculum is a big deal. It’s visibility — seeing posters and pictures in the classroom that reflect your heritage, seeing the contributions of your heritage. But instead, there’s just been a complete erasure.”

And the effects of that erasure are plainly evident in the findings of the ACLU’s report, Baldy says.

“Why is it so difficult for Native students?” she asks. “It’s because the curriculum disempowers them, it disempowers their stories. But we could make a curriculum that empowers Native youth, that teaches about resilience and moves into revitalization and resurgence.”

###

In many ways, Virgil Moorehead may understand the challenges facing Humboldt County’s Native youth better than most. Of Yurok and Tolowa descent, Moorehead grew up on the Big Lagoon Rancheria and attended McKinleyville High School before leaving the area to go to college. After ultimately getting a doctorate in clinical psychology and attending a fellowship at Stanford University, Moorehead returned to Humboldt and is now the executive director of Two Feathers Native American Family Services based in McKinleyville.

A tribally chartered nonprofit run through the Big Lagoon Rancheria, Two Feathers provides mental health and wellness services to local Native youth and families and recently, in partnership with Northern Humboldt Unified and Klamath-Trinity Joint Unified school districts, began offering school-based programming as well. While the nonprofit has been around for more than two decades, it rapidly expanded over the last few years to meet what is increasingly seen as a desperate need for increased culturally relevant mental health services for Native residents.

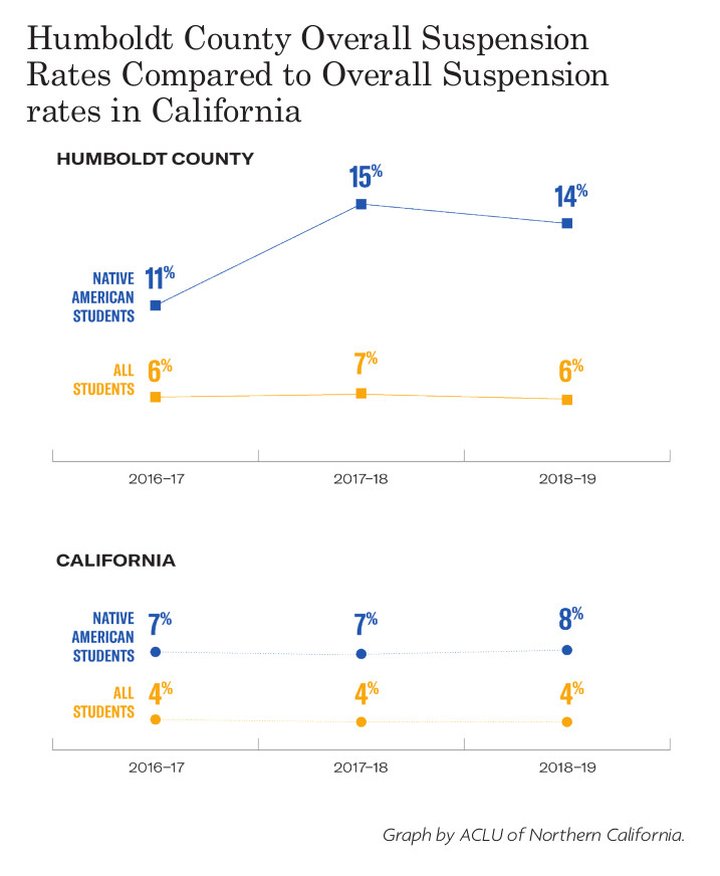

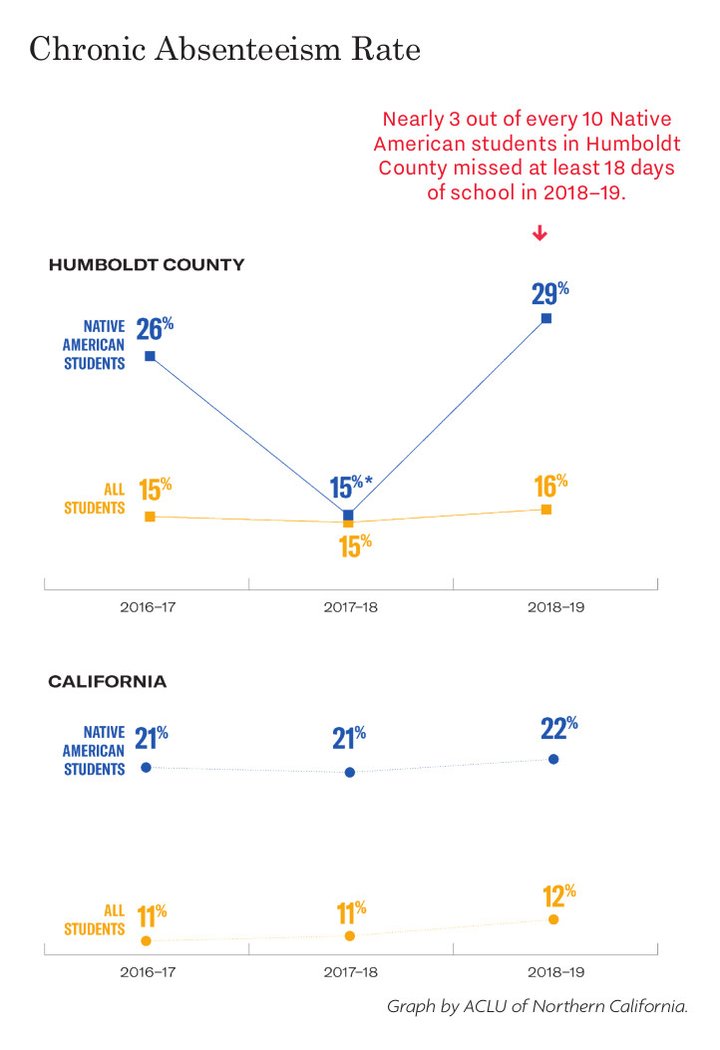

Having worked intensively with local Native youth, Moorehead says he wasn’t entirely surprised to see in the ACLU’s report that an average of almost 14 percent of local Indigenous students faced school suspensions between 2016 and 2019, more than double the rates of Humboldt County students overall and nearly four times those for California as a whole. Nor was he particularly surprised to see that nearly a quarter of Native students missed at least 18 days in a school year over the past three years.

“I think it was shocking but not surprising,” Moorehead says of the report. “Native folks are struggling and the statistics show they’re struggling more than any other group.”

And Moorehead says the report underscores what was already painfully clear — increased mental health services are a critical need on the North Coast. This was brought into sharp focus in 2016, when the Yurok Tribe declared a state of emergency after seven tribal members between the ages of 16 and 31 committed suicide in an 18-month span.

Thanks in large part to some grant funding, Moorehead says Two Feathers has has grown from a small organization with three or four staff members to employing 29 people — two thirds of them Native — in just a few years, which allowed it to go from seeing 40 kids in 2019 to providing more than 400 with counseling and mental health services in 2019.

In Hoopa, Moorehead says Two Feathers has been able to increase access to mental health and wellness services almost tenfold for students by offering a smattering of services, from one-on-one counseling and small “wellness groups” to afterschool and mentorship programs.

In health and education circles, more attention is being paid to adverse childhood experiences (“Reaching for Resilience,” Oct. 1). Known as ACEs, these 10 childhood experiences — which range from physical and emotional abuse to having an incarcerated relative or a parent struggling with substance abuse — can cause toxic stress and have been linked to poor health and behavioral outcomes later in life. The ACLU report notes that Humboldt County has the highest rates of ACEs but also suffers from a dearth of school-based mental health professionals.

Specifically, the report notes that student-to-professional ratios for school counselors and psychologists are 20 percent higher than the state average, while the ratio of students to nurses is twice as high as the state’s. And all those ratios are two to six times higher than what professional associations recommend, according to the report.

“In the 2018-19 school year, 31 districts in Humboldt County did not employ a social worker and only one district — Cutten Elementary School District — had a part-time social worker on staff,” the report states. “Similarly, nearly 90 percent of districts in Humboldt County — 28 districts in total — did not employ a single school nurse. The data were not much better for other mental health professionals: 17 school districts in Humboldt County did not employ a counselor and 22 did not have a psychologist on staff.”

While it’s too soon to quantify the impact of Two Feathers’ work in Hoopa and Northern Humboldt Unified High School District with state data, Moorehead says he’s confident it will be profound, noting that when quantifying access, it already has been.

While generational trauma isn’t officially defined as an ACE, most agree there’s no question it can act similarly when it comes to triggering toxic stress and contribute to the conditions that do qualify as ACEs. For example, Native people in Humboldt County are more likely to live in poverty than their non-Native neighbors and face disproportionate incarceration rates, while also seeing higher mortality rates from everything from car crashes to cardiovascular and liver disease.

This reality can’t be ignored in the school setting, Baldy says.

“Students can’t leave their trauma at the classroom door — it affects them every day,” she says. “We’re talking about communities with really high ACEs scores.”

Baldy also points out that there’s a correlation between students suspended from school ending up in the juvenile justice system and, later, jails and prisons in what’s known as the school-to-prison pipeline, contributing to a generational cycle of trauma.

For his part, Moorehead says he agrees with so much of what he sees in the ACLU report — the need for better curriculum, less punitive discipline measures, more mental health and wellness services. But he says these are smaller pieces to a larger puzzle, which is how to help entire neighborhoods and communities break free of intergenerational patterns of poverty, trauma and dysfunction.

And if schools are going to be successful in breaking those cycles, he says, it’s going to mean truly partnering with the community and outside organizations to offer a wide array of services — from culturally relevant curriculum and culturally appropriate counseling to mentorships and even the kind of community events that evoke a sense of pride.

“Yes, we have to focus on the individual and the family and the school, but we also have to look at how we change and improve neighborhoods,” he says. “We often medicalize and individualize social problems … but how do you improve neighborhoods? How do you change the perception and expectations and the norms within the community and have kids start to feel like, ‘Wow, I’m glad I’m being raised in this part of the county, in this community, in this neighborhood?’”

###

The Journal reached out to Eureka City Schools Superintendent Fred Van Vleck and Humboldt County Superintendent Chris Hartley to comment for this story. Van Vleck didn’t respond. Hartley offered that a lot of the disparities are “truly a school district based situation,” as the county office of education just provides various support services. But as the report points out, Hartley said Humboldt County does have high rates of ACEs, which directly impacts students’ mental and physical health, as well as substance abuse, attendance and abilities to access education.

“The data in this report clearly indicates areas for growth and systemic change, with the disproportionality identified among Native students being greatly concerning,” Hartley said in an email, adding that county staff is already working to bring enhanced mental health services, inclusive discipline practices and more culturally inclusive curricula into Humboldt County classrooms. “We fully endorse the recommendations of the report and are working to assist the implementation of many at this time.”

The ACLU’s report concludes by deeming the data it presents as a “call to action for parents, educators and leaders to find solutions and resources to address the crisis of under-education, de facto exclusion and failure to provide meaningful supports for Indigenous students.”

The report includes 11 specific recommendations — from hiring more mental health professionals and adopting more culturally relevant curriculum to moving away from exclusionary discipline models and districts developing memorandums of understanding with local tribes and service providers. But Simon, for her part, says she hopes people walk away from the report with the idea that they all have a part to play in turning the tide.

For teachers, she says the report offers a host of resources to help incorporate Native perspectives, experiences and cultures into their classrooms. For district leaders, there are tangible suggestions of how to forge better relationships with Native communities. And, Simon says, the report itself can serve as a tool the community as a whole can leverage when applying for grants or outside funding.

Reflecting on her own experience in local schools, where she experienced a host of experiences she looks back on as inherently racist, Baldy says parents, teachers, school staff and community leaders can recognize the need to take strong anti-racist stands to send the firm message that everyone has value, everyone’s culture is important and worthy of respect. She recalled a time on the playground when her classmates were playing “cowboys and Indians,” with the cowboys pretending to tie one of their classmates to a poll and set him on fire.

“Me, watching it as an Indian kid, it was just so much violence,” Baldy says, adding that aside from her family, she never recalls anyone at school intervening to stop it, nor any of the other racism she endured.

Baldy recalls a number of public incidents over the past couple of years when racial slurs or epithets were directed at Native high school athletes, saying those were missed opportunities for the community to “really strongly push back against any racism.”

“It needed a coordinated kind of county, city, school district response for everyone to say, ‘This is not OK,’” she says, but that swift, multi-layered response never came. “I hope this can help our teachers and leaders understand their role in teaching and promoting anti-racism, an anti-racism pedagogy.”

With the ACLU’s report now done, Marshall says her work is just beginning.

“My role is to have a plan ready to go with superintendents,” she says, explaining that she’s here to help teachers and administrators enact the report’s recommendations, whether it’s revamping discipline models or classroom curriculum. “We’ve laid it out, how you can do this in your school and do it now. There are 11 bullet points of recommendations and a model that we’re hoping schools will follow.”

Over the past decade, the ACLU hasn’t hesitated to take larger steps to push for change, having filed lawsuits or federal complaints against school districts in Del Norte County, Eureka and Loleta that all spurred settlements and action plans. But Marshall says she hopes this time the report proves enough.

“We’re hoping that everyone’s goal is to solve this problem,” she says. “Nobody wants to file a lawsuit. That’s the last resort.”

She says the report is hitting at a pivotal moment when many have awakened to issues of social and racial justice, when there’s a renewed vigor among many to take a critical eye to old norms, to find new solutions and rectify historic wrongs. And she says she’s hopeful that people will recognize that more just discipline practices in local schools and a renewed focus on student wellness and mental health, coupled with a curriculum that honestly and fully recognizes the culture and history of this place and its people, will be good for everyone.

“It really has to do with fighting this systemic white supremacy we’re facing and embracing this anti-racism that’s so important at this moment,” Marshall says.

Read the ACLU’s full report here. Educators wishing to contact Rain Marshall can contact her at rain@ncidc.org.

###

Thadeus Greenson (he/him) is the Journal’s news editor. Reach him at 442-1400, extension 321, or thad@northcoastjournal.com. Follow him on Twitter @thadeusgreenson. The Community Voices Coalition is a project funded by Humboldt Area Foundation and Wild Rivers Community Foundation to support local journalism. This story was produced by the North Coast Journal newsroom with full editorial independence and control.

CLICK TO MANAGE