Alyssa Jenkins uses the state’s MyTurn website to try to book a vaccination appointment for someone on April 19, 2021. Photo by Anne Wernikoff, CalMatters

###

For months, Alyssa Jenkins logged countless hours on MyTurn, California’s COVID vaccine registration site as she searched for precious appointment slots for her fellow teachers.

“I’d become obsessed,” said Jenkins, who teaches high school English in Pacifica. “I was living in the system.”

When MyTurn debuted in mid-January, it was supposed to be a one-stop shop, a place where every Californian could register to be notified when they became eligible for the COVID vaccine and eventually make an appointment for their shot.

Instead, it’s become a lightning rod for many Californians frustrated by their inability to get vaccinated quickly and return to a normal life.

Appointments booked on MyTurn — an average of about 100,000 each day — account for only about 27% of the vaccinations given each day across the state, according to data from the California Department of Public Health.

MyTurn was developed with unusual speed for a government website.

State officials told CalMatters that they spent $50 million building the site. A contract obtained by CalMatters shows up to $18 million will be paid to multinational consulting giant Accenture. Of that, $6.9 million was spent on development, but there’s another $5.7 million management cost in the first year and another roughly $6 million a year for two more years. Accenture used technology from Salesforce, a San Francisco-based software company, and was assisted by a workforce management consulting company called Skedulo.

MyTurn isn’t just an appointment clearinghouse. It has other critical functions: It tracks vaccine orders and distribution, collects reams of vaccination data and helps organize volunteers statewide. It can also transmit data to California’s immunization registry, which maintains confidential vaccination records.

But it is the public side of MyTurn that has drawn the most criticism.

San Francisco County Supervisor Matt Haney said “it’s better to have a statewide vaccine site than nothing at all” but “MyTurn has at times been glitchy.”

“I’m disappointed that we never created a pre-registration system (like) a lot of other states have had. Instead, people have to check the site multiple times a day,” he said.

“It’s so unnecessarily inefficient. I do believe it’s creating a lot of stress and anxiety, and it creates equity issues.”

so, so frustrating! FWIW I brought it up with the UCD Health staff when I went for my 💉 #2 this morning and they said they’d look into it. but it seems to be a systemic issue with MyTurn, not a one-off glitch 🤬

— Ted Flynn (@TedFlynn) April 16, 2021

A confluence of problems with MyTurn continues to frustrate many Californians: The technology was hastily deployed, leading to inevitable glitches because it wasn’t vetted enough before it was unveiled. It can’t reliably cope with the state’s constantly changing rules and wide variety of local eligibility qualifications. And the vaccine supply hasn’t kept up with demand, so until very recently, appointments were unavailable for most people.

MyTurn has systemic problems, too. It does not incorporate doses sent by the federal government to pharmacies, and various systems from health care providers haven’t yet signed up or aren’t integrated.

In essence, creating a one-stop vaccination app isn’t as easy as booking a delivery through DoorDash.

“There’s an expectation that everything’s as convenient as a Google app, but nothing’s as complicated as what we’re doing.”

— Matthai Chakko, spokesman for the city of Berkeley

For weeks, state health leaders have urged patience as Californians flocked to MyTurn, noting that MyTurn is a work in progress and that it’s one — but not the only — way to sign up for COVID-19 vaccinations.

“We have made great progress in making MyTurn the ‘Front Door’ for those seeking COVID vaccine,” said Darrel Ng, a spokesman for the state’s COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force.

Rather than build on the state’s existing vaccine registry, California’s health department created a new one from the ground up. California maintains online systems to track childhood vaccines and flu shots, but nothing that could handle managing vaccinations for up to 40 million people.

The system is largely overseen by Blue Shield of California, which was tapped by Gov. Gavin Newsom in a no-bid contract to manage statewide vaccine distribution.

“Everybody’s doing the best they can, but (the technology) needs a lot of support,” said Matthai Chakko, spokesman for the city of Berkeley, which runs its own public health department. “There’s an expectation that everything’s as convenient as a Google app, but nothing’s as complicated as what we’re doing.”

Some technology and health care experts have been highly critical of MyTurn, blaming it on the state’s lack of technological expertise.

“Everybody is making this up on the fly. MyTurn, in particular, is a usability nightmare. The site clearly favors already tech-savvy users and doesn’t appear to have been properly vetted,” Arien Malec, senior vice president of research and development at Change Healthcare, told Kaiser Health News.

Indu Subaiya, president and cofounder of Catalyst@Health 2.0, a digital health consulting firm, said her research has shown that “there isn’t a one size fits all” solution that works nationwide. “Different populations of folks, based on health literacy, access to broadband and technology literacy, will have different needs,” she said.

Bewildering results for faraway sites

MyTurn can schedule appointments for mass vaccination sites, such as Moscone Center, and for some sites run by county health departments. But it cannot schedule appointments for the retail pharmacies and grocery stores in California that receive vaccine doses directly from the federal government. It can’t make appointments for homebound seniors, and it doesn’t include most nonprofit community clinics.

MyTurn also can’t directly schedule appointments for large medical providers like Sutter Health, Stanford and Kaiser Permanente because their data systems can’t talk to MyTurn’s systems. Instead, the website directs people to outside websites, where they have to go through the same process all over again.

As a result, some MyTurn searches return bewildering results that would daunt all but the most persistent vaccine seekers.

For instance, searching for Berkeley ZIP codes on the site brings up faraway vaccination sites in Novato and Stockton. Berkeley created a how-to video to help people use MyTurn because of its confusing interface.

In another example, a recent search for an appointment in many Santa Clara County ZIP codes yielded a “No Appointments Available” message. Most people don’t know that if they scroll down, they’ll see links to numerous sites in the county with available appointments that can’t be booked on MyTurn, including the Levi Stadium mass vaccination site.

“If you have a site you’re directing everyone to, but it’s missing key locations, that creates confusion,” said Haney, who frequently posts on social media to alert people to open vaccine appointments.

Entering the ZIP code for Dodger Stadium into MyTurn, for example, fails to turn up the mass drive-through vaccination site at the stadium. That’s because it’s managed by Carbon Health, which doesn’t interface with MyTurn.

Different qualification restrictions in counties make it hard for people to know where they can schedule an appointment, as some vaccine venues restrict their appointments to people in certain counties or even neighborhoods, Haney said. That’s particularly challenging in the Bay Area, where many people live in one county and work in another.

Blue Shield, under pressure to speed vaccinations, particularly for vulnerable Californians, now requires vaccine providers to sign up with MyTurn to more closely monitor how quickly doses are going into arms – with the threat of not getting weekly allocations if they don’t comply.

Some counties, including Santa Clara County, resisted and ultimately signed less restrictive agreements with Blue Shield. Santa Clara County kept its own vaccine appointment system, making its clinics and the Levi Stadium mass vaccination site far less visible on MyTurn.

MyTurn was revamped earlier this month as all Californians ages 16 and older became eligible to be immunized. About one million users came to the site on April 15, the day eligibility expanded to people 16 and older.

Bigger vaccine allotments have made it easier for people to get appointments. Blue Shield officials promise that more vaccine providers will be added to the site as California’s vaccine supply continues to expand.

For people without Internet access or who encounter problems online, the system includes a phone number, 833-422-4255, that people can call, including language translation, to make appointments.

‘Vaccine fairies’ drop in to help

“Vaccine fairies” and other volunteers have emerged to help less computer-savvy Californians, particularly seniors. Many of them bypassed MyTurn.

Sunil Patel, a 39-year-old Oakland resident who works in the pharmaceutical industry, joined the national nonprofit “Vaccine Fairy” network to help book COVID vaccine appointments for others. He said he’s booked about 60 appointments in California, but only two were on MyTurn.

“It’s just rarely the best option,” Patel said. “I don’t blame people for thinking there was no vaccine available,” Patel said.

Jenkins, the teacher from Pacifica, wouldn’t call herself a vaccine fairy, but she spent so much time on MyTurn that her son Adam, a software developer, built her a bot to refresh it automatically in hopes of surfacing newly available appointments as soon as they dropped.

It is one of a number of automated computer programs that enterprising developers created to make vaccine searches on MyTurn and other sites a slightly less Herculean task.

“I could not bear to watch. She was just refreshing the site all the time and I just thought to myself, there’s got to be a better way,” said Adam Jenkins, who is 24.

When he got an email from California’s chief information security officer, he thought it would be a cease and desist order. Instead, the official lauded his work and offered him an API key that lets MyTurn recognize the bot as friendly — an implicit recognition that its site was so problematic that it needed such outside aids.

Alyssa Jenkins said she’s booked more than 400 appointments for others.

“The system’s convoluted, we gave people almost too many choices, we didn’t explain rules of road, then we change the rules of the road,” she said.

“No wonder people want to throw their computers out the window.”

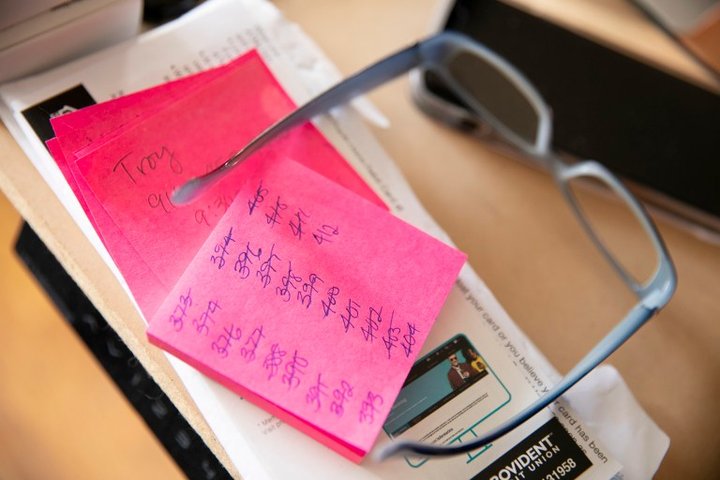

Alyssa Jenkins’ notes show she has made vaccination appointments for more than 400 people, many of whom she has never met, since February. She said this is her way of connecting to the Jewish concept of Tikkun Olam, which means to repair the world. Photo: Anne Wernikoff, Calmatters.

Ryan Gruver, director of the Nevada County Health & Human Services Agency, said there were “hiccups” when his rural county in California’s gold country first joined MyTurn. “It went up incredibly fast,” he said of the system.

The site isn’t helpful for some of the county’s most remote residents, where Internet service can be unreliable.

But he said the ability to draw data from the site about who has been vaccinated will help the county fine-tune its efforts to reach people.

“The first couple of months was about keeping up with demand,” Gruver said. “Now we’re making sure we don’t leave anyone behind.”

###

CalMatters COVID-19 coverage, translation and distribution is supported by generous grants from the Blue Shield of California Foundation, the Penner Family Foundation and the California Health Care Foundation.

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE