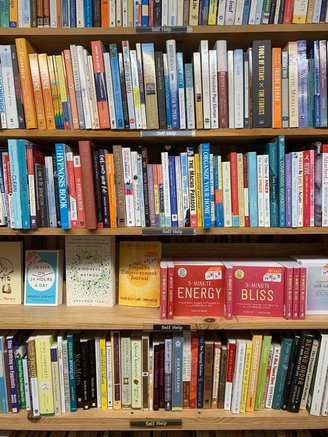

“So what is the appeal of self-help books,” I asked. I’d just come from Eureka Books, where I innocently inquired if self-help books were still being published. In my naivety, I assumed they’d gone the way of hula hoops and pet rocks. My disillusion complete — see photo — I was soon in conversation with my pal as we tried to understand their continued attraction (Amazon lists over 100,000 books under the “self-help” category.)

Photo: Barry Evans.

“Yeah, if they actually worked, why are they still selling?” pondered my skeptical friend. “It’s not like they’re fresh on the scene.” We agreed that if it’s happiness you’re after — presumably the bottom line — then the world’s best-seller, the Bible, can certainly lay claim to being an early self-help book (although it has the good sense to guarantee happiness, not now, but in the next life, assuming you play your cards right). Speaking of the Bible, that’s the only book that Samuel Smiles’ classic Self-Help, “a collection of inspirational stories about hard working men rising through the ranks,” didn’t outsell in 1859, the year of its publication (—also the year of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species). By the time of Smiles’ death 45 years later, his book had sold over a quarter of a million copies. It’s available on Project Gutenberg.

Probably the next Big Thing in self-help books was How to Win Friends and Influence People by farmer-turned-public-speaker Dale Carnegey, later Carnegie (in honor of Andrew Carnegie). It came out in 1936, and has sold over 30 million copies (including 17 editions the year it was published!). I treasure one of Carnegie’s insights and only wish I faithfully followed through on it: “Remember that a person’s name is, to that person, the sweetest and most important sound in any language.”

Back to our coffee-shop musing on why, if self-help books worked, were they still sell in astronomical numbers? “Maybe we’re looking at this the wrong way,” I said. “We’re thinking in terms of, ‘Have readers’ lives gotten better after reading one of them?’ What about the enjoyment of the actual process of reading, never mind what happens afterwards?”

Does this make sense? When we read a self-help book, we’re imagining a future in which we’re happier/richer/healthier/slimmer/better parents/sexier lovers/more disciplined writers. Etc, etc. Which feels great, right? The simple act of reading is a joyous experience as you or I fantasize about our Better Life Ahead. Out of the gate come the reward chemicals — dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine and all the rest — and we’re (deep breath) happy. At this point, there’s no motivation for actually doing what the book says (assuming it’s any good, which is questionable): you’re already blissed out! And — this is the genius of the genre — there’s always another when we’ve finished this one. It’s brilliant, and risk-free (other than the cost of the book itself). So long as we don’t have to prove that we’re capable of making the changes the book encourages, we can’t fail. This approach, it turns out, has a name: The Inspirational Life.

I know whereof I write. I bought myself a keyboard a few months ago, deciding that it was time, well into my seventies, that I learned how to play. And I can’t start to tell you the pleasure I’ve been having watching YouTube videos aimed at beginners who, purportedly, want to learn piano. Every one of these brings me joy as I imagine myself dancing merrily through Erik Satie’s Gymnopédies, impressing all those who marvel at my finger dexterity and soulful understanding of the music. All without actually sitting down and playing! (Full disclosure: I can manage the first six or eight bars of the first one, played very slowly.)

But suppose you do get up from the couch and decide to act on what you’ve just read by the self-help guru-de-jour? Bottom line: Change is hard! Change can lose us friends and family. Change can mean giving up that evening glass of beer or wine (reward for a hard day’s work). Change can lose us jobs, spouses, freedom. It’s usually uncomfortable and it hurts.

And for what? Dan Gilbert, whose job title should be “happyologist” (he’s a psychology professor at Harvard who studies happiness for a living — check out his 2006 book Stumbling on Happiness) sums up the entire “my life will be better in the future if I do this now” paradox. He writes, “We treat our future selves as though they were our children, spending most of the hours of most of our days constructing tomorrows that we hope will make them happy.” A Scientific American reviewer completed the thought: “But the children turn out to be ingrates, complaining that we should have let them stay in the old house or study dentistry instead of law…Like the fruits of our loins, our temporal progeny are often thankless.”

It was time to get ourselves second cups of coffee and resume our joy-filled kvetching.

CLICK TO MANAGE