Even if you don’t give a tinker’s damn about Mars or space or extraterrestrial life, for sheer graphics, this three-minute “How to Land on Mars” animation is soul-stirring, imho. Please give yourself the treat of watching it (with sound on), then carry on reading.

This is what wakes me up, anytime I’m getting cynical about life, politics, the environment: the fact that we humans, with our three-pound brains optimized for surviving in the African savanna a few million years ago, can design, build and land a vehicle like Perseverance on Mars. If all goes well, this Thursday afternoon, our species will be able to say:

- Not only can we send a spacecraft to Mars (currently farther from Earth than Earth is from the sun), but we can land within a predetermined area about the size of the City of Eureka

- We have figured out how to decelerate a one-ton machine from 12,000 mph to a gentle landing (1.5 mph) in just seven minutes. (Actually, we already did this with a smaller, lighter machine, Curiosity, in 2012.)

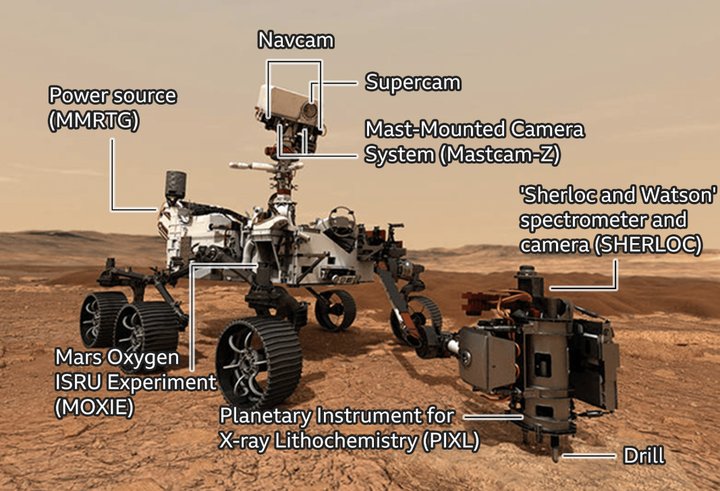

- We have sent a helicopter drone to Mars, capable of flying in the thin—one percent that of Earth—atmosphere to take photos (via both black-and-white and color cameras) that will help scout Perseverance’s future route on the surface and check out areas the rover can’t reach. All autonomously.

- We’ve safely landed a rover capable of drilling into the surface, obtaining samples and storing them for a future mission to retrieve and return to Earth for analysis.

And humans have figured out how to do this in just 64 years—a couple of generations—after launching the first object into space, an Earth orbiting two-foot diameter aluminum alloy sphere named “Sputnik 1.”

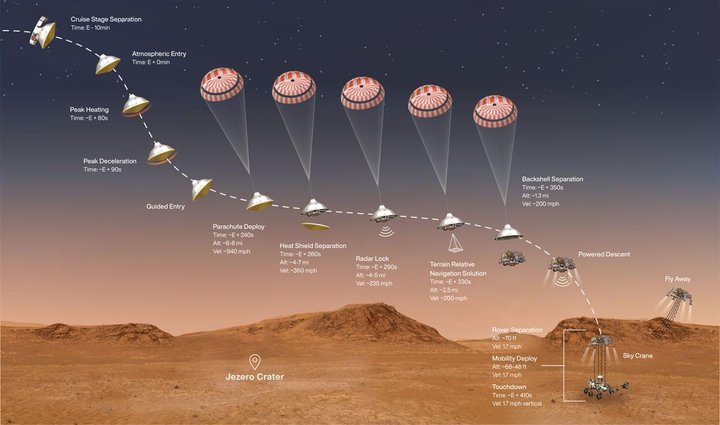

To appreciate the magnitude of the achievement, consider what’s involved in landing Perseverance on the Martian surface. Landing a spacecraft safely on Earth is comparatively easy, due to our planet’s thick atmosphere: “aero-braking,” combined with parachutes, is a well understood re-entry process. Mars, with its thin atmosphere, presents a different challenge. Skimming across the top of the Martian atmosphere, Perseverance, protected by its heat shield, decelerates from 12,000 mph to less than 1,000 mph in four minutes, after which a new piece of technology, a “range trigger,” instructs the craft to deploy its supersonic 70 ft. diameter parachute at just the right moment. The ’chute has to be sturdy—it initially slows Perseverance down to 360 mph in just 20 seconds.

Seven-minute landing sequence (NASA)

Following separation of the “backshell” attached to the parachute, rockets slow the landing even more, If Mars wasn’t dusty, that would do it—the rockets would bring Perseverance down for a safe landing. But in fact, the rockets would kick up so much dust that the craft’s delicate instruments might be damaged, which is why the crazy-looking “skycrane” is used, to let the rover rappel safely down on three 25 ft. nylon tethers from its rocket-powered “jetpack.” As soon as Perseverance touches down, the tethers are cut and the jetpack flies away to a crash landing.

Here’s the thing: this all happens completely automatically. Earth is 11 radio minutes distant, so there’s nothing anyone back here can do if something goes wrong. By the time we receive a signal saying that the descent has started, Perseverance will, hopefully, already be sitting safely on the Martian surface. That’s assuming every one of hundreds of computer-actuated processes has worked correctly and on time. For instance, the angle of entry has to be just right; the timing of parachute deployment has to be perfect; all the rockets need to fire impeccably; and there’s no second chance for the pyros—small explosive devices—to sever the tethers. One malfunction and eight years of development and $2.7 billion goes kaput. (Is that a lot? It’s Disney’s global box office takings for Avengers: Endgame; or 33 hours of DoD spending…)

(NASA)

Mars

is not for the faint-hearted! I hope you’ll join me watching the

white-knuckle show on Thursday. Check here

at 11:15 am Humboldt time.

CLICK TO MANAGE