“…the Greeks…always found ways to emphasize the power and beauty of the naked body. Dressing this torso and giving it color was a way to make the body sexier.” (Archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann)

###

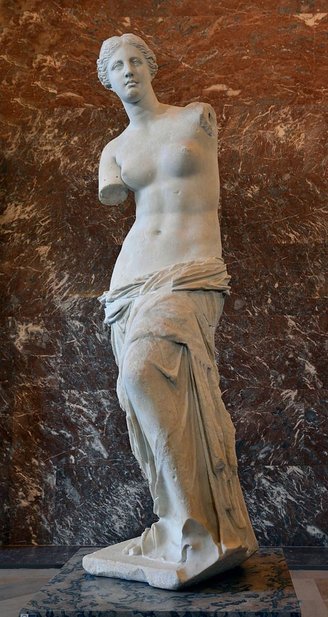

Photo: Livioandronico2013, via Wikimedia. Creative Commons license.

Think of a classical statue and you’ll probably come up with something like the Venus de Milo (greeting visitors to the Louvre, halfway up the main staircase)—pristine marble, pearly white, not a trace of actual color. Which isn’t how the ancient Greeks originally saw her 2200 years ago on the Aegean island of Milos. She was almost certainly colored, painted with bright colors: green (from malachite), blue (azurite), yellow and ocher (arsenic), red (cinnabar) and black (burnt bone).

We know this because most statues from ancient Greece and Rome still have barely-visible flecks of paint on them. (As added evidence, consider Helen of Troy’s lament about her beauty in Euripides’ play about her: “If only I could shed my beauty and assume an uglier aspect/The way you would wipe color off a statue.”) Time and weathering did the wiping, and now such traces aren’t obvious—researchers have had to tease out the original colors with ultraviolet cameras and high-intensity lamps. But when they’ve done so, the results are spectacular.

Take, for instance, this archer, dated to 500 BC, which many archeologists believe is actually a rendition of Helen’s abductor Paris, the dude who caused the Trojan war, according to the Homer and the other long-ago storytellers. German archeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann not only found sufficient flakes of color to determine the statue’s original polychrome appearance “with a high degree of confidence,” using physical and chemical analyses; he recreated the archer in plaster, painting it with the same mineral and organic pigments the Greeks used over two millennia ago.

Trojan archer (Paris, perhaps), c. 500 BC, from the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia on the Greek island of Aigina. It’s now in the Stiftung Archäologie in Munich. Photo: Bibi Saint-Pol, via Wikimedia. Public Domain)

Vinzenz Brinkmann’s plaster reconstruction of how the statue originally looked. Photo: Marsyas, via Wikimedia. Creative Commons license.)

Fast forward to the Renaissance. Michelangelo and other Florentine sculptors of that era didn’t realize that time had erased the colors of the ancient statues, so they carved their masterpieces in white Carrara marble. To this day, lily white is the norm for marble statuary.

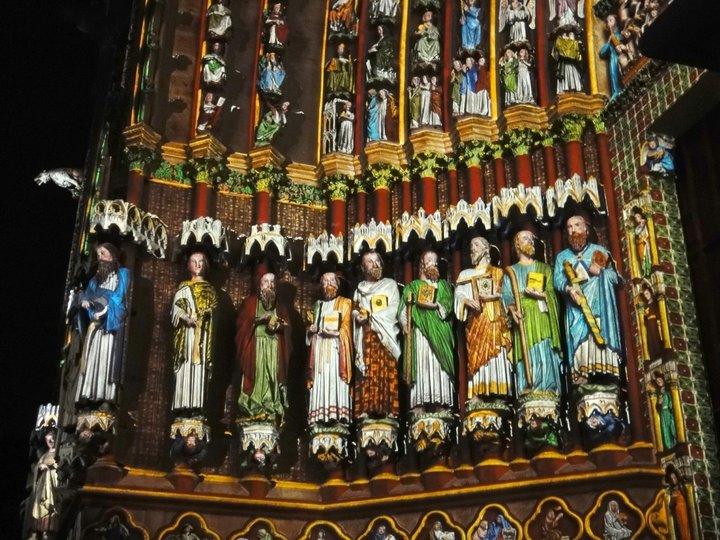

Reading about these colorful Greek statues reminded me of my pilgrimage, ten years ago, to several of France’s 30-odd Gothic cathedrals built in 12th and 13th centuries. From Paris, I visited Chartres, Amiens, Beauvais, Rouen and Reims. In particular, Amiens, where, nearly 30 years ago, technicians who were engaged in cleaning hundreds of statues on the cathedral’s west portal found flecks of paint on virtually every figure. Experts concluded that the present gray stonework was once flamboyantly colored! How to recreate the original appearance without damaging the existing stone? Kodak to the rescue.

At night through summer months, eight powerful projectors now bathe the facade of the cathedral with light shone through Ektachrome transparencies, colored in strict accordance with the restorers’ findings. As the projectors slowly come up, the statues magically turn from gray to polychrome—a riot of blue, red, orange, yellow and green—restoring what hundreds of years of sun and rain had eroded. The illusion is perfect: the statues are painted. There’s no outward sign that the color is projected (other than the projectors themselves!). I was taken back to the Middle Ages, in thrall to the spectacle, feeling like a humble pilgrim from 800 years ago.

West portal, Amiens cathedral, by day. (Amiens photos by

Barry Evans):

Amiens photos by Barry Evans.

And by night:

One of eight projectors creating the illusion of colored statues:

CLICK TO MANAGE