In the fall of 1960 I was just getting used to living away from home, taking my first engineering classes at the University of London, when the verdict came in: Lady Chatterley’s Lover was not obscene, and therefore couldn’t be banned from libraries in the UK. Three decades after its author’s death, Penguin Books risked their reputation and bank account when they published an unexpurgated cheap paperback edition of LCL in November 1960 — all 200,000 copies sold out on the first day. Until then, it was pretty much a given that in Britain, any book with “fuck” and (especially) “cunt” was obscene and therefore couldn’t be sold cheaply. Book publishers got around the law by either selling expurgated versions (“Wanna do coitus, luv?”) or by pricing daring French novels (oh, those Frenchies…) out of the reach of “the common man,” whose morals could be perverted by explicit words on the printed page.

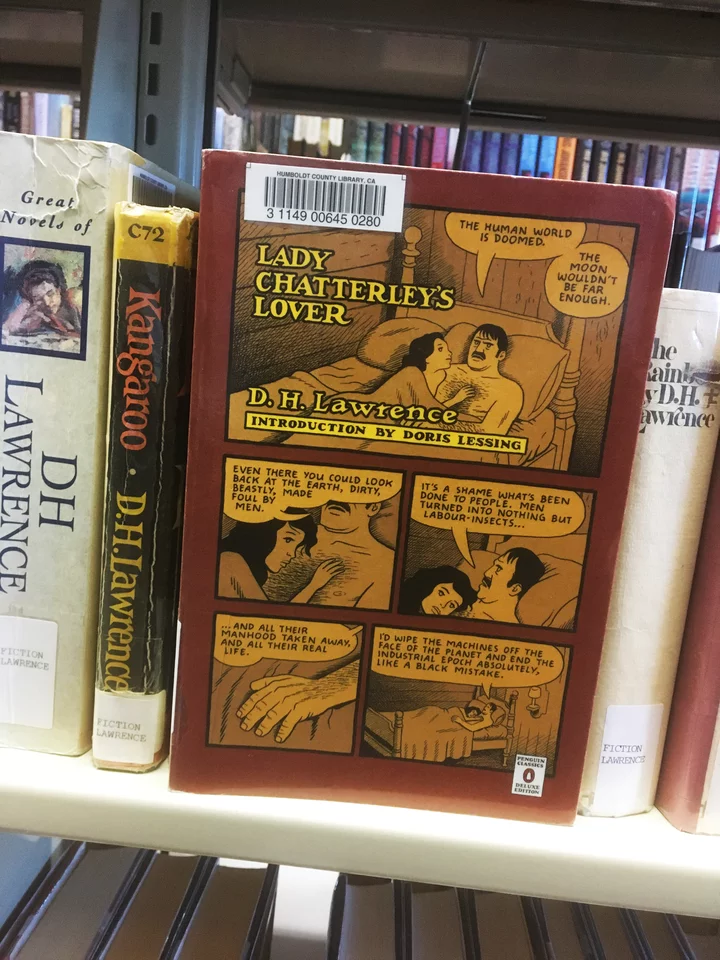

And now, a graphic graphic novel! At your local library. (Michael Logan)

The book itself, beyond its explicit use of a few four-letter words, is an easy and poignant read. D.H. Lawrence’s last novel, it was written in the late 1920s. It’s the story of doomed love between Lady Connie Chatterley, married to a man (Sir Clifford) paralyzed from the waist down from a WWI injury, and Oliver Mellors, their gamekeeper. For me, the message is that love stemming from the mind is rarely enough, and that physicality completes love. (Of course, reading it now, it comes over as an anachronism: the few British institutions that survived WW1 didn’t make it past 1945.)

I’m reminded of this reading a recent piece in the New York Times about increasing attempts at book-banning in the U.S. which, it claims, “…have grown in the U.S. over the past few years from relatively isolated battles to a broader effort aimed at works about sexual and racial identity.” The main battlegrounds, apparently, are public libraries. While school boards have the power to demand that “undesirable” books be pulled from students’ reading lists, the same students, now alerted to which books they shouldn’t be exposed to, will (duh) head down to their local libraries. And that’s where the real battles are being fought these days, between community leaders — town and city councils, pastors and the like — and librarians.

J.K.Rowling’s Harry Potter series topped the “most challenged” books 2000-2009. Witchcraft! Daniel Ogren, via Wikimedia. Creative Commons license.

Most,

perhaps all public libraries in this country have adopted the

American Library Association’s Freedom to Read statement. A couple

of excerpts: “The freedom to read is essential to our democracy…

Most attempts at suppression rest on a denial of the fundamental

premise of democracy: that the ordinary individual, by exercising

critical judgment, will select the good and reject the bad. We trust

Americans to recognize propaganda and misinformation, and to make

their own decisions about what they read and believe. We do not

believe they are prepared to sacrifice their heritage of a free press

in order to be “protected” against what others think may be bad

for them. We believe they still favor free enterprise in ideas and

expression…” And therefore “There is no place in our

society for efforts to coerce the taste of others, to confine adults

to the reading matter deemed suitable for adolescents, or to inhibit

the efforts of writers to achieve artistic expression.”

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has been attacked from the get go, for racism and the N-word. Life Magazine, no photographer listed. Public domain.

The real issue with banning a book from a library is that the instigator of the ban is making that decision for everyone. Fortunately, here in Humboldt, our County Library has been subject to very few attempts at banning any books: “We haven’t really seen much of that here — a couple challenges here and there, but it’s been a few years since the last (knock wood),” according to one library insider. But, seeing as how books have been banned pretty much forever — Gutenberg’s Bible was only one in a long history of censorship (by the Vatican, in this case) — we should stay awake to the possibility it could resurface here. These days, it’s LGBTQIA+ topics that most offend those who would ban books.

BTW, I’m happy to report that The Catcher in the Rye (consistently a book-banning target for “offensive language, sexually explicit, unsuited to age group”) was required reading when I was, I think, 15. And if you want a primer on what might happen if the idea of banning books really took off, I recommend Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451.

CLICK TO MANAGE