Last

week, a commentator objected to my use of the phrase “quantum leap”

when describing the James Webb Space Telescope. My initial reaction

was, Well shit, if

squeezing a 22-foot diameter telescope, together with its five-layer

tennis-court size sunshield, into the 16-foot nose cone of a rocket,

and subsequentially unfolding it in space, doesn’t count as a

quantum leap, what does? Surely

that technological marvel, 20-odd years and tens of thousands of

people in the making, is much more impressive than James Bond

figuring out how (once again) to battle the Spectre organization in

Quantum of Solace,

not to mention Verizon’s Quantum internet, Duracell’s Quantum

battery, Quantum Corporation’s automation tools … and many more

quantums/quanta to boot.

The

commentator seemed to be convinced that the only legitimate use of

“quantum leap” was as it applied to quantum

mechanics, which sent

me scurrying to the many online etymological sites. How could

something as small as a quantum jump in QM have made it into the

prosaic meaning — my meaning — of quantum leap, “an abrupt

change, sudden increase or dramatic advance,” as Merriam-Webster

has it. (Sorry commentator!)

Quantum,

from Latin quanta

(how much) had been in use long

before Max Planck, in 1900, introduced the term in his revolutionary

formulation of physics, single-handedly introducing the world to what

became quantum physics, the world of the very small. For instance,

Edgar Allan Poe (may his name be praised) used the term, rather

obscurely, in his 1832 story Loss

of Breath: “I would

have the judicious reader pause before accusing such asseverations of

an undue quantum of absurdity.” Anyone want to parse this?

Early

(pre-Planck) physicists glommed onto the word. For instance, when

physician/physicist Julius von Mayer wrote to a colleague outlining

what we now call The First Law of Thermodynamics (energy can be

neither created nor destroyed, only transformed), he used “quantum”

simply as a synonym for “quantity.” That was in 1841, and the

word became a handy go-to term for 19th century scientists trying to

figure out what energy was and how it worked.

In 1900, Max

Planck brought science into the modern world when, singlehandedly, he

created the science of quantum mechanics, the foundation of all of

quantum physics: quantum chemistry, field theory, information science

and more. His insight came as he was researching “black-body

radiation” spectra, that is, the way objects change color when

they’re heated. By assuming that energy was emitted and absorbed in

tiny discrete packets, instead of continuously, Planck turned

conventional physics on its head. He called these packets “quanta,”

in the process deriving one of the most important physical constants,

h, the eponymous Planck constant. To say this constant is small is an

understatement; it’s ridiculously, crazily small. For his epiphany,

Planck received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1920.

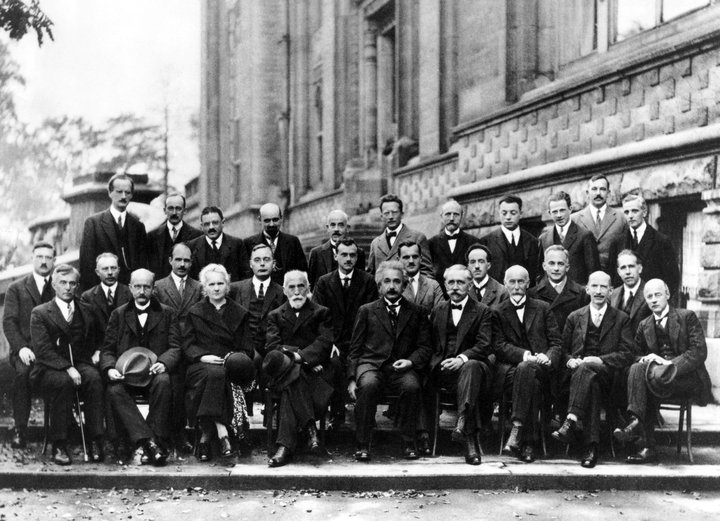

Four giants of physics sitting side by side in the front row at the 1927 Solvay Conference: Max Planck, Marie Curie, Hendrik Lorentz and Albert Einstein. (Benjamin Couprie, Institut International de Physique de Solvay. Public domain)

One of the main beneficiaries of Planck’s discovery was young Albert Einstein, who in 1905 — his annus mirablis — published no less than four papers that changed our view of the world and our place in it. One of these papers proposed that a beam of light doesn’t consist of a wave, as was thought at the time, but rather can be thought of as a series of photons, discrete quanta of energy, foreshadowed by Planck’s black-body radiation insight. For this (not for the theories of relativity), Einstein was awarded his Nobel Prize in Physics two years after Planck, in 1922. (The prize money went to support his ex-wife and children.)

The, er, quantum leap from tiny to huge wasn’t made until 1956, according to the OED, quoting a writer who discussed the US-Soviet nuclear arms race: “The enormous multiplication of power, the ‘quantum leap’ to a new order of magnitude of destruction.”

And that’s the rest of the quantum story.

###

CORRECTION: Barry, you idiot! Max Planck’s surname has a “C” in it. The Outpost regrets Barry’s error. —Ed.

CLICK TO MANAGE