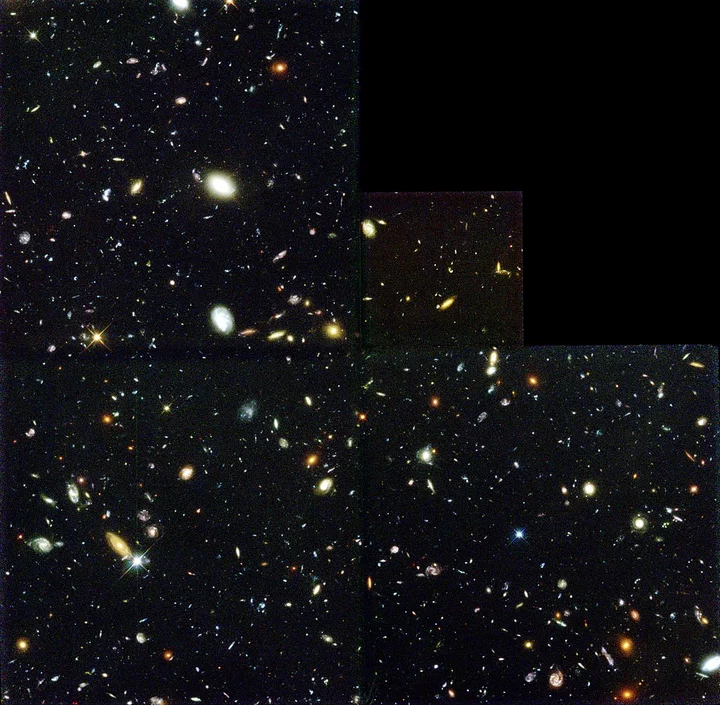

“There were literally thousands of galaxies in an area of the sky

that up until that particular image we didn’t know anything

existed. It told us once again that we have no clue. We think we’re

smart? We have no clue.” (Charles Bolden Jr., Former NASA

Administrator)

The original Hubble Deep Field image, released in January 1996, showing thousands of galaxies in a tiny, apparently empty patch of sky. (NASA, ESA, STScI, public domain)

Bolden was referring to the above “Hubble Deep Field” (HDF) image, distilled from over 300 separate exposures taken over a ten-day period at four different wavelengths in December, 1995. Imagine peering at the night sky through a drinking straw: that’s the size of the field of view seen here. Astronomers took several months to pick a target patch of sky to investigate, at an unprecedented level of detail. Among their criteria: look perpendicular to the plane of our Milky Way galaxy to avoid peering through dust; and avoid any nearby bright sources of visible or infrared light. Basically, they wanted to investigate a seemingly empty part of the night sky to see what lay beyond the range of most telescopes. In the end, the field chosen (out of an initial list of 20 potential targets) lies just “above” the left-most star (Megrez) of the dipper of the Big Dipper.

The field of view

here is so small that, of these 3,000-odd objects, less than 20 are

foreground stars in the Milky Way. Everything else here is a

galaxy—spiral, elliptical, irregular—each comprising millions upon

millions of stars; there are an estimated 100,000 million stars in

our galaxy. (Three years later, a similar “empty” patch of sky

opposite the original HDF, yielded similar results, thus lending

credence to the “cosmological principle,” that we live in a

typical region of the universe.)

The HDF is a

remarkable image, one that inspired astronomers to push for a

successor to Hubble. This culminated (finally!) last week, with the

release of the first science images from the newly-commissioned James

Webb Space telescope, or JWST. The very first one, released last

Monday, was another “deep field” view, similar to Hubble’s but

looking even farther back in time. Whereas Hubble can see objects as

they were about 500 million years after the Big Bang, JWST can see

back to when the universe was just 200 million years old. For more on

this, check out my columns on JWST here

and here.

The first JWST image to be released centered on a galaxy cluster nearly five billion light years distant, although one of those red specks is over 13 billion light years away (almost as old as the universe). The huge mass of the cluster causes distortion of some farther galaxies by “gravitational lensing.” This image “is approximately the size of a grain of sand held at arm’s length,” according to NASA’s press release.

The next day, NASA released five more images, including this one, the “Cosmic Cliffs of Carina Nebula,” a young star-forming region close to us in the Milky Way: light left there a mere 6,000 years ago.

I submit, if you’re not totally gobsmacked by all this, you’re just not paying attention.

CLICK TO MANAGE