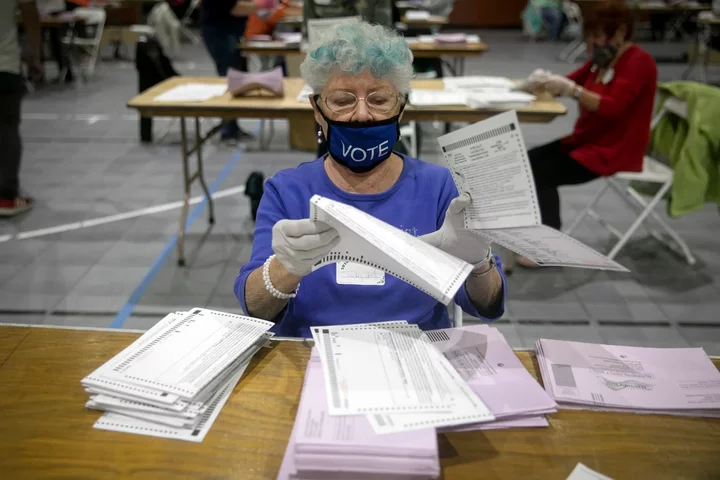

Elections volunteer Judy Moon extracts ballots from mail-in envelopes in Martinez on Oct. 31, 2020. Photo by Anne Wernikoff for CalMatters.

Rich Kinney readily concedes: Making it onto California’s November election ballot is a miracle.

The 66-year-old associate pastor and former mayor of San Pablo in the Bay Area is running to unseat Democratic Assemblymember Buffy Wicks out of staunch opposition to her support for abortion rights.

What did it take for him to make the Nov. 8 ballot? Only about 60 signatures to qualify as a Republican write-in candidate for the June 7 primary, and a mere 37 votes to finish in the top two.

Wicks won 85,180.

Kinney, the only other official candidate in the Assembly District 14 primary, said the write-in process allows newcomers a chance to move forward without the challenges of fundraising against an incumbent.

“Going around my district and trying to get funding was ridiculous. No one wants to give funding to a campaign that’s not going to get out the gate,” he told CalMatters.

While some candidates might spend millions of dollars or months campaigning, California’s top-two primary system means that in races with only one other candidate, it’s possible for a write-in candidate to sneak into second place with very little support.

For the June 7 primary, state Assembly and state Senate candidates needed as few as 40 people to sign nomination papers to qualify as write-in candidates. And no matter how few votes they won, as long as they finished in second, they advanced to the November election.

This year, Kinney wasn’t the only one to win fewer than 50 votes and make it onto the ballot. Thomas Edward Nichols, a Libertarian running against Republican incumbent Jim Patterson of Fresno in Assembly District 8, made it with just 15 votes. Mindy Pechenuk, a Republican in Assembly District 18, advanced to a matchup with Oakland Democrat Mia Bonta with just 31.

In total, nine write-in candidates moved on to the general election in state Assembly races, and two for state Senate seats.

But while getting onto the ballot is one feat, winning the race is another. It’s a reality that Kinney acknowledges.

“I really understand that it’s next to impossible to be able to unseat a sitting Democrat in the Legislature,” said Kinney, who ran unsuccessfully for state Assembly in 2014 and for state Senate in 2016. “But we’ve got to put up a good fight anyway. It’s important that voters who care about the decency of life have an opportunity to rally together and say so.”

Christian Grose, academic director of the USC Schwarzenegger Institute for State and Global Policy, said while it’s a quirk of the election system that write-in candidates can make it to the ballot with so little support, it’s not necessarily a problem caused by the top-two primary system or by the write-in process.

“It’s the lack of serious competition from formal Republican and Libertarian candidates,” he said. “Basically, it’s the lack of organized challengers that’s the problem.”

Because of the write-ins, only two candidates for 100 legislative seats have a free pass on the Nov. 8 ballot: Republican Assemblymember Vince Fong of Bakersfield and Democratic Assemblymember Reggie Jones-Sawyer of Los Angeles. (Democrat Giselle Hale, mayor of Redwood City, withdrew last week for the open Assembly District 21 seat in Silicon Valley, but her name will still appear on the ballot with Diane Papan, a San Mateo City Council member and now the only active candidate.)

Fair or futile?

The write-in process was established in California in 1911 as part of the Progressive Era political reforms, according to Alex Vassar, communications manager at the California State Library.

Prior to that, political parties would hand out “tickets” to voters — essentially filled-out ballots.

“One of the major goals was to empower individual voters and weaken the ‘political machines,’ and give voters the ability to make separate decisions in each election contest. California adopted what was called ‘the Australian ballot,’ which was essentially the modern secret ballot that we know and love today,” Vassar said.

Only a handful of write-in candidates have won either legislative or congressional seats in the last century. Vassar said it was “beyond rare” — in 1930, 1936, 1944, 1958 and 1982.

When U.S. Rep. C. F. Curry died in office in October 1930, his son, C. F. Curry Jr., won the seat the next month as a write-in, defeating a Republican, a Democrat, and two independents. When Assemblymember Lee Bashore died in September 1944, he had already won both the Republican and Democratic nominations. Three write-in candidates ran, and Ernest R. Geddes was elected with 45.9% of the vote, according to Vassar.

“It lets people onto the playing field, but not onto one of the teams,” said Thad Kousser, a professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego. “It allows candidates entry, but then places a mountain to climb still for write-in candidates.”

Even if the write-in candidates are political unknowns, it creates more competition for the general election, Grose said.

“It’s probably a nuisance for these incumbents who will probably win,” he said. “They’re going to do a little more work, and that’s not so bad.”

In an April meeting of the Santa Monica Democratic Club, state Sen. Ben Allen acknowledged that to keep his seat, he had to beat a write-in candidate — Kristina Irwin.

“She seems like a very nice person who watches way too much Fox News, and she’s just kind of, like, adopted all the crazy Republican conspiracy theories,” Allen said at the event, according to the Santa Monica Daily Press. He added that being pushed to campaign more aggressively would be a good thing.

Irwin won 6,260 votes in the primary — far more than the 213 earned by another write-in candidate in that race, but 159,000 votes fewer than Allen.

In Orange County, write-in candidate Leon Sit, a 19-year-old engineering student at UCLA, advanced to the general election with 551 votes from Orange and San Bernardino counties.

That result “reinforces that the voice of each and every voter matters, that every vote counts,” Orange County Registrar of Voters Bob Page said in an email. From an election operations standpoint, Page said the write-in process does not create any additional work or challenges.

Sen. Ben Allen has taken at least $583,000 from the Finance, Insurance & Real Estate sector since he was elected to the legislature. That represents 14% of his total campaign contributions.

Sit said he used social media to gather support, and was also interviewed by local reporters, which increased his name recognition.

Still, he said, “statistically the political winds are not in the favor of a challenger like me.” And if he somehow beats Republican Phillip Chen, he might have to cut back on his course load or even take a break from school.

“I didn’t come into this to be a legislator,” Sit said. “I did it to give the district a choice between two candidates, even if one of those candidates was a 19-year-old college student.”

Nichols, who is up against Patterson, won a spot on the November ballot with even fewer votes, just 15. Like Sit, he knows unseating the incumbent is a long shot.

Patterson has been in the Legislature since 2012, The district, which encompasses the Central Valley and parts of the Sierra Nevada, is largely Republican.

Still, Nichols said he was motivated to run to get the Libertarian Party’s message before voters and to raise the issues he sees in his local community, especially the increased cost of living due to fire threats – specifically, homeowner and property insurance.

Nichols says he’s glad the write-in process exists — and that it could give voters a way to think “outside of the duopoly that dominates our political culture.”“I’ve got to say, I really appreciate the fact that an engineer up here in the foothills could wind up on the ballot going after an incumbent,” he said. “I’m satisfied with the democratic process in that respect.”

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE