Cal Fire Battalion Chief Brad Niven from Sonora battled to get workers’ comp after he suffered PTSD and considered suicide. Photo by Julie Hotz for CalMatters

California’s firefighting agency has been slow to react to a mounting mental health crisis within its ranks as firefighters around the state say Cal Fire has failed to get them what they need — including a sustainable workload, easier access to workers’ comp benefits and more counselors.

While climate change is driving enduring drought and ferocious fires ravaging California, nature can’t be blamed for all of Cal Fire’s problems: The state’s fire service, which prides itself in quickly putting out wildfires, has failed to extinguish a smoldering mental health problem among its ranks.

Many firefighters told CalMatters they are fatigued and overwhelmed, describing an epidemic of post-traumatic stress in their fire stations. Veterans say they are contemplating leaving the service, which would deplete the agency of their decades of experience. Some opened up about their suicidal thoughts, while others — an unknown number since Cal Fire doesn’t track it — already have taken their own lives.

Interviews with Cal Fire firefighters, including many high-ranking battalion chiefs and captains, and mental health experts paint a picture of the state agency’s sluggish response to an urgent and growing crisis:

- Cal Fire has an unyielding policy of 21-day shifts and forced overtime. Staffing is insufficient as firefighters battle thousands of fires year-round, sometimes for 40 days in a row, year after year. The nonstop work and increasing overtime are contributing to on-the-job injuries and post-traumatic stress disorder.

- The workers’ comp system is difficult to navigate for firefighters suffering from post-traumatic stress, even suicidal thoughts, beginning with skepticism among managers about the legitimacy of their unseen wounds. Some say to get help or be reimbursed for mental health care, they have to hire lawyers, who told CalMatters that claims are routinely denied.

- In California’s rural areas, where many Cal Fire employees are based, there are inadequate numbers of qualified mental health care providers. And many won’t accept workers’ compensation cases because of the extensive paperwork and low compensation. As a result, firefighters say they can’t find help when they desperately need it.

- Work conditions and stress are driving an exodus from the department, which loses invaluable institutional knowledge and field experience. Last year 10% of Cal Fire’s permanent, non-seasonal workforce quit.

- Firefighters say suicidal thoughts and PTSD are rampant. But Cal Fire collects no incidence data on suicides or PTSD. Experts say the agency can’t develop an effective program to combat them if they don’t understand and monitor their scope.

- Cal Fire’s behavioral health unit ramped up slowly despite the growing problem. Although created in 1999, it had no permanent budget and no permanent employees for 20 years. It began with one staffer — and six years later there were two. Now it has 27 peer-support employees, who assist a permanent and seasonal workforce of more than 9,000.

Cal Fire’s growing budget reflects the priority California places on fighting wildfires as they intensify and spread. The agency’s base budget for wildfires has grown by nearly two‑thirds over the past five years alone, from $1.3 billion in 2017‑18 to $2.1 billion in 2021‑22. The total budget, which includes resource management and fire prevention, has also increased about 45% in the same period, to $3.7 billion.

The California Legislature has maintained a laser focus on combating wildfires, in part because of the breathtaking cost to suppress them: In the last 10 years, Cal Fire has pulled $7.5 billion from the state emergency fund to fight fires, including about $1.2 billion in the past year.

Despite the large investment, the funds have not kept pace with staffing needs: Days with extreme fire risk have more than doubled in California over the last 40 years. Every year, Cal Fire responds to nearly half a million local emergency calls in addition to thousands of wildfires. Last year alone, almost 9,000 wildfires scorched the state; the millions of acres burned in recent years have set new records.

“I recognize that the cumulative toll is taking an effect on our people. To be honest, it’s taken a toll on me as well.”

— Joe Tyler, Cal Fire chief

When asked about the problems facing his crews, Cal Fire Chief Joe Tyler, who was appointed in March, acknowledged in an interview with CalMatters that “the fatigue and working long hours on large, destructive fires” is taking a toll on their health and wellness across the state.

Tyler vowed in the interview to make the mental wellbeing of his employees “my number one” priority. “I recognize that the cumulative toll is taking an effect on our people. To be honest, it’s taken a toll on me as well,” he told Calmatters, adding that he once worked a fire for 56 straight days.

Asked why the agency he oversees is failing to protect its firefighters from PTSD, California Resources Secretary Wade Crowfoot said “there’s no absolute, silver-bullet solution.”

“We’ve taken a big step forward,” he said, with a proposal in Gov. Gavin Newsom’s 2022-23 budget to add $400 million for relief staffing and permanent Cal Fire personnel.

“They need to be able to come off the front lines during fire season, and have periods of rest, reconnect with families. It’s an incredible strain. In some cases firefighters haven’t been home for months,” Crowfoot said.

“This is a complex challenge that requires resources and support in a lot of ways. I would not suggest that if we are able to get funding for staffing, it will solve the problem.”

he dangerous work of California’s firefighters is honored at the California Firefighters Memorial on the state Capitol grounds in Sacramento. Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

Former Cal Fire Chief Thom Porter, who retired last year after three years as the agency’s commander, said “more needs to be done” to address the agency’s staffing problems, long hours and PTSD among firefighters.

“Part of what needs to be done is recognition that we don’t have enough firefighters in service at any level — state or local,” Porter said. “We need our elected officials at all levels to increase those numbers. People can’t recover from these kinds of stressors without rest away from the job.”

Overworked, under stress

An administrative claim notice from Cal Fire’s firefighters’ union had a Dickensian tone, like a logbook from a 19th century sweatshop: Forced overtime, punishing working conditions, little sleep, workplace injuries, an inhuman system of indenture.

“Employees have been known to work 30 days or more without any time off due to forced overtime, and the most egregious cases include employees on duty for 49 days or more straight without a day off. Overworked beyond the point of exhaustion,” says the claim, which union attorneys sent in February to the state’s Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal OSHA) and the Labor Workforce Development Agency.

“CAL FIRE employees have sustained physical injuries and routinely experience fatigue, sleep deprivation, stress, and mental distress,” the union wrote, describing the emotional toll, including divorce, alcoholism and substance abuse, of what it called “excessive hours.”

“Other CAL FIRE employees are quitting their job to find relief from the pressure,” the union attorneys wrote. “Even worse, some employees’ emotional distress is so severe that they have committed suicide or experienced suicidal ideation.”

The document requested that the state’s workplace regulatory agencies investigate unsafe work conditions at the fire stations, which are staffed by Cal Fire under contracts with cities and counties.

Cal OSHA rejected the request, saying it has no jurisdiction because there are no workplace standards for overtime and it is not illegal for employers to make employees work long hours as long as they are compensated.

The staffing problems stem from Cal Fire’s contractual obligation with local stations in 36 counties to handle all emergency calls, including structure fires, rescues and medical aid, while also being dispatched to battle wildfires statewide.

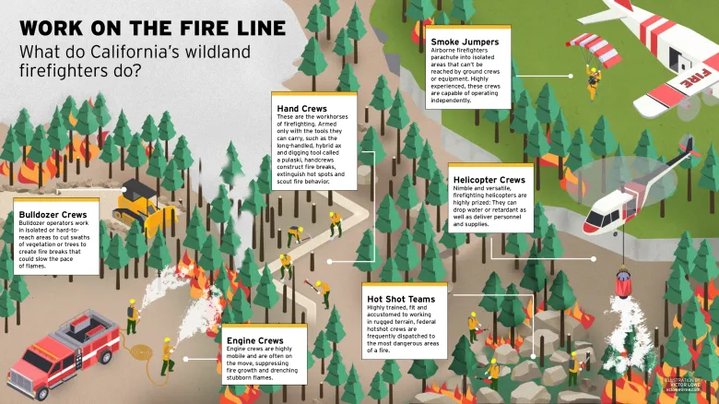

Illustration by Victor Lowe. Click to enlarge.

Gary Messing, a labor lawyer for Cal Fire’s union, Local 2881, said California is out of step with the work rotations of other first responders. Cal Fire has shifts of 21 days, while federal firefighters work 14-day shifts. The union is negotiating with Cal Fire over the issue as part of its collective bargaining process.

“The solution is easy to articulate and hard to accomplish: Reduce the number of hours,” Messing said. “Our people work 72 hours a week. The first thing that could be done is to put Cal firefighters on a 56-hour week. That’s a start.”

The Legislative Analyst’s Office noted in a recent analysis that despite bumps in firefighting staffing and budgets, California’s relentless fires “can still strain response capacity.” In 2020 alone, Cal Fire was unable to dispatch personnel and equipment to thousands of fires: “Roughly 7,900 requests for fire engines, 900 requests for dozers, and 600 requests for helicopters could not be filled.”

The proposed Fixing the Firefighter Shortage Act of 2022, which has been approved by the Senate but has not yet cleared the Assembly, could address some of Cal Fire’s staffing problems. The bill would add about 1,300 firefighters to the state’s ranks at an estimated cost of almost $300 million per year; it would also increase the number of firefighters per engine and attempt to stop forced overtime.

“We are at critical mass, guaranteed, right now,” said Mike Orton, a Cal Fire captain and former Marine who has undergone counseling for PTSD. “These people in fire stations are not going to get relief for years because the state system takes so long to work. The people who are working here are jumping ship like no other. People like me are pulling the ejection handle.”

“The people who are working here are jumping ship like no other. People like me are pulling the ejection handle.”

— Cal Fire Capt. Mike Orton

Unlike most workers, when firefighters make a mistake because of stress or fatigue, their actions can endanger the public.

“At the end of the day, all of the well-intentions in the world, and the mental health awareness, the opportunity to go to trauma retreats, doesn’t help when the bell goes off,” Orton said.

“How do we face the public and say, ‘We decided to close your station today because these guys are tired.’ That’s not a decision our managers are going to make.”

One of the core problems is the simple, intractable math: As fires are more frequent, burning longer and more difficult to fight, California does not have enough firefighters to perform all the tasks the state asks of them.

“If you can’t fill all the positions in your battalion, the way the system Is designed, nobody goes home until the positions are filled,” said Battalion Chief Jeff Burrow, referring to daily work shifts. “If I can’t fill those positions, I’ve got to reach out to the battalion next to me, and nobody in that battalion gets to go home. It just spreads. We run out of people all the time.”

‘Denial, denial, denial’

California’s workplace insurance system instructs stressed workers to follow a prescribed path to get relief: Report the problem to your superior, talk to a peer counselor to get referred to a mental health professional, keep your receipts and apply for workers’ comp.

Medical help is the endgame. Workers’ compensation benefits, paid by the state, cover the costs, which average $60,000 for first responders’ cases, according to a Rand Corp. estimate. But the barriers to firefighters’ claims are myriad.

Randy Thrash, who manages Cal Fire’s Occupational Health Program, said finding clinically competent mental health providers outside of large cities is a “huge challenge. They are difficult to find in the rural areas where a lot of our staff lives.”

Even when mental health clinicians can be located, it’s another struggle to identify those willing to take workers’ comp insurance patients, Thrash said. “They don’t want to deal with the billing and reporting requirements of workers’ comp. They prefer to deal with private insurance.”

That creates another layer of bureaucracy for a firefighter seeking help: If someone receives a PTSD diagnosis from a private insurer, those medical records — which are confidential by law — must be made available to the state. If that doesn’t happen, the diagnosis must be verified by a state-qualified medical examiner. The process can take months for a firefighter to be reimbursed for medical care.

A current bill, introduced by three Democratic senators, would cut the time period to investigate PTSD workers’ comp claims from 90 to 60 days, and states that if the claim is not rejected within that timeframe it would be presumed to be eligible for compensation. The proposal has cleared the Senate and is in the Assembly.

The long wait for workers’ comp insurance “is hugely frustrating,” said Gena Mabary, Cal Fire’s injury and accommodation manager. “When you are dealing with psychiatric stress, you are already stressed out. It adds another layer of stress. It means that sometimes people won’t go through the process.”

Cal Fire workers’ comp claims for mental health problems “are more frequent. I am expecting them to increase still more,” Mabary said. No data, however, was available.

“Comprehensive national data on first responder mental health do not exist,” said a 2020 Congressional Research Service report on federal efforts to address the mental health of first responders. The authors reported that barriers to accessing mental health services are particularly problematic among firefighters, where a “culture of not seeking help” exists.

Mynda Ohs, a San Bernardino-based counselor specializing in treating first responders, said Cal Fire “has no idea how to proceed with a mental health injury versus a physical injury.”

One of her Cal Fire patients suffering from PTSD had to hire an attorney to pursue a claim, and even then the case took two years to resolve. “They put him through the ringer, ” Ohs said. “It’s more trauma on top of trauma.”

“When you are dealing with psychiatric stress, you are already stressed out. (The long wait for workers’ comp) adds another layer of stress.”

— Gena Mabary, Cal Fire injury and accommodation manager

In 2020, a state law recognized that all first responders engage in stressful and dangerous occupations, and made PTSD “presumptive” for workers’ comp benefits — codifying that a mental injury is a legitimate medical claim, although it must still be proven. That law sunsets at the end of 2024.

Before the law was enacted two years ago, California firefighters’ PTSD cases were denied workers’ comp benefits 24% of the time — almost three times more often than their claims for other medical conditions, according to a RAND Corp. report. They were also denied more often than PTSD cases filed by people in other occupations.

Yet the current system is still stacked against those filing claims, according to an attorney representing firefighters who dispute workers’ comp rejections. He said many are denied.

Cal Fire ‘has no idea how to proceed with a mental health injury versus a physical injury.”

— Mynda Ohs, counselor specialized in treating first responders

“Denial, denial, denial,” said San Diego attorney Scott O’Mara. “It’s very, very common. Adjusters’ training is to contain and control costs. They need to pull back and allow these people to get the care. They delay and deny treatment. It’s horrendous.”

Workers’ comp claims begin with an adjuster at the state’s nonprofit insurance provider, the State Fund. If the claim is denied, challenges can move their way, slowly, to the state’s Division of Workers’ Compensation, which is the final arbiter.

Battalion Chief Brad Niven successfully navigated the workers’ comp insurance system for his mental health claim after he began considering suicide, but not without difficulty. He said he has at least 18 friends and peers who have faced the same problems he did.

“I’ve heard horror stories from people whose boss has not supported them, who say, ‘You are making this stuff up, you are not sick. You are trying to get out of coming to work’. You have to sit down with a psychiatrist and you have to relive those experiences. People who have issues, myself included, don’t want to relive them,” Niven said.

“They are looking at it from a financial standpoint, not wanting to approve the claim, not wanting to pay it out. You are guilty until proven innocent. You have to go above and beyond to prove your case.”

Turnover: ‘People are leaving in droves’

Far from being walking recruitment posters for Cal Fire, many fire service veterans bluntly said they are ready to leave the organization they love — and they give that unvarnished advice to their colleagues. The agency is losing experienced employees who either accept quieter, better-paid first responder jobs or opt to retire and collect a pension.

Burrow said his Riverside staff is operating at about 50% capacity. “You’d be hard-pressed to talk to someone in the department right now that isn’t looking for other avenues in their life,” he said.

He added, “people are leaving in droves.”

“My entire battalion — we have people leaving all the time or retiring earlier, which is where I’m at,” said Burrow, 49. “For the people that work for me, I advise them to move on. I can’t in good conscience tell them to stay. We have people quitting the academy now. That was unheard of 20 years ago. That speaks volumes.”

Cal Fire officials initially disputed that people are leaving in large numbers, saying their staffing levels have been fairly consistent.

But data released at CalMatters’ request shows that about 10% of its workforce quit last year. The number of firefighters and other personnel who left in 2021 was 691, nearly twice the average for the previous four years, according to numbers provided by Cal Fire spokesman Chris Amestoy.

‘For so long it was in the dark.’ And often, it still is

There have been few attempts at legislation to address the mental health of the state’s wildland firefighters.

A 2017 bill would have created a peer-support program for a broad range of first responders that included a strict confidentiality component. It made it through the Legislature and to then-Gov. Jerry Brown in 2018 for his signature.

In the month that the bill sat on the governor’s desk, two Cal Fire employees committed suicide, according to Assemblymember Tim Grayson, the bill’s author. Brown ultimately vetoed it, objecting to the scope of the confidentiality, which he said could jeopardize workplace safety.

Grayson, a Democrat from Concord, revived the measure the next legislative session, with a more-narrow focus on creating a pilot program of peer support for local or regional firefighters. That legislation was signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom, although it has a sunset provision in two years.

Grayson said it took three years to convince colleagues that mental health problems were increasing at Cal Fire, in part because the agency collects little data.

“There’s been a shift — people are talking about this. For so long it was in the dark,” he said. “We’re talking about lives here. Not just lives of the firefighters, but their family and children, everybody is impacted by the wellbeing of our first responders. It would behoove us to invest in the mental health and wellbeing of our first responders. They do lay their lives on the lines for us.”

Porter, Cal Fire’s recently retired chief, said firefighters are starting to open up more about their PTSD and share their heart-wrenching stories.

“It’s been an incredibly moving experience to have people opening their personal lives and talking about things that never would have been talked about before. In my career, up until the last three years, I have never heard some of this. It’s alarming,” he said.

But getting help is problematic in a service where tough-guy traditions persist. Mike Ming, who oversees Cal Fire’s employee support program, saw firsthand the “walk-it-off” mentality as a young firefighter. When he told a supervisor that a traumatic work experience was bothering him, “He said, ‘Suck it up, buttercup,’ and told me to pull up my skirt.”

While that attitude is fading, Ming said, there remain “some holdovers, some 30-year grumpy captains. We do also have in management some folks who say, ‘I sucked it up, why don’t they suck it up?’ I don’t know if we are ever going to get away from having some aspect of that.”

Dennis King, 76, who retired as a battalion chief after 22 years with Cal Fire, may be one of those holdovers. He wonders “if the pendulum has swung so far.”

“The state has always had a very liberal policy. The phone rings in the morning at the station and I go, “Who’s calling in sick today?’ Everyone says, ‘I think I have the flu.’ We have people who are serial hypochondriacs. There’s always people who are going to take advantage of this system.”

Cal Fire leaders “will always tell you there’s no punitive action against anybody who admits to PTSD. But it does affect their career.”

— Mike Feyh, former captain, Sacramento City Fire Department

Today, when mental health issues are raised among wildland firefighters, it’s still in hushed tones. There’s a stubborn stigma attached to discussing PTSD or trauma.

“They will always tell you there’s no punitive action against anybody who admits to PTSD,” said Mike Feyh, a former captain with the Sacramento City Fire Department. “But it does affect their career. There were very few times that I saw someone who has struggled with a mental health issue rise to the top of an organization or take a leadership position. They kept it to themselves.”

Ernie Marugg, a former Cal Fire battalion chief who is in the process of seeking a medical retirement for PTSD, said the agency culture is, “If you need help you are weak and if you are weak I don’t want you around me. It’s like you are contagious,” he said.

A slow reckoning at Cal Fire

Until recently, Cal Fire’s behavioral health program was bare-bones. The program had only one staffer when it began in 1999 and six years later, there were two. Now Cal Fire has 27 employees in its peer-led program — all of them with their own stories of addiction, suicide attempts and trauma — to help a statewide workforce of 6,500. These peers do not offer formal counseling, they mostly listen, and then, if warranted, send employees to therapists for help.

But Cal Fire still doesn’t collect much data on mental health, and what information it does gather is often squirreled away in departments that don’t talk to each other. Some Cal Fire staffers bemoan the agency’s antiquated and cumbersome data management.

For example, its behavioral health program collects numbers of “contacts” — calls to a helpline and visits in person from a peer advisor. But, rather than focusing solely on issues such as PTSD, the numbers include those seeking advice about an array of other topics, such as parenting, financial problems and legal issues.

When CalMatters asked Tyler, the Cal Fire head, why his agency doesn’t have data on incidence of PTSD and suicides, he said he will soon meet with the behavioral health team to discuss “strengths and weaknesses and threats to the program.” He said the data related to mental health needs to be improved.

The 2012 Strategic Plan, Cal Fire’s guiding document updated every seven years, devoted two pages to the value of physical fitness and calisthenics. There was no discussion of PTSD or mental health.

Cal Fire now preaches the importance of mental health awareness and the no-strings approach to asking for help. The latest plan, from 2019, for the first time acknowledges suicide as a problem. Now each station house has pamphlets and fliers tacked onto bulletin boards with information about PTSD and suicide prevention. Classes about PTSD and suicide awareness have recently been added to the Cal Fire academy’s curriculum.

The names of fallen firefighters are inscribed at the California Firefighters Memorial on the Capitol grounds. By Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

Behavioral health experts point to the U.S. Armed Forces as a model for integrating mental health programs alongside physical well being.

The Defense Department has studied and reported on the health of American troops for 30 years. In 2021 the military asked the Rand Corporation to perform a similar analysis, considered a critical tool to understanding the impacts of the long deployments and inherent dangers. “Exposure to traumatic events, combat in particular, is a well-known hazard of military service. PTSD can contribute to military attrition, absenteeism, and misconduct,” the report said.

The U.S. Forest Service, which manages the nation’s largest wildland firefighting force, says it is focusing on PTSD like never before.

“Over the past several years, understanding the mental health impacts on firefighters has become a high priority,” said E. Wade Muehlof, a deputy national press officer with the Forest Service in Washington, D.C., citing the length and intensity of the fire season as factors.

The federal agency has an expanded employee assistance program and a new provider with on-call “trauma-trained clinicians.” In addition, it tasked a new behavioral health steering committee with developing programs.

But even as the need has come into sharper focus, a gap in services for first responders remains.

The nonprofit National Fire Protection Association identified an acute shortage of programs to treat PTSD and trauma among firefighters. Its 2021 national assessment found that nearly three-quarters of fire departments do not have behavioral health programs for their employees. Of those that do, 90% offer help for post-traumatic stress but few other mental health services.

“We are really good at preventing fires, why don’t we work on preventing this?,” said Patrick Walker, a Cal Fire battalion chief. “There’s a tendency to kick people when they are down, instead of pulling them up. That’s got to change.”

A life saved

Intervention, if it comes in time, can save lives. Niven can attest to that.

In late 2019 the battalion chief, who is based in Sonora, was struggling with depression and suicidal thoughts. They became overwhelming after he drove through an intersection where, five years earlier, he was unable to save the life of a young woman hit by a logging truck.

He couldn’t shake the memories. “I thought to myself, ‘Is this it? Am I going to commit suicide?’,” Niven, 47, said in an interview. But he didn’t reach out for help, “I thought I could fix it.”

During a flight to Sacramento, he made a plan: He would kill himself by jumping off the top floor of the airport parking garage.

A flight attendant who saw him crying sat next to him and asked how she could help. She arranged for Niven to text a friend, who put him in touch with a counselor from Cal Fire’s employee support program, who then stayed with Niven on the phone for two hours after the plane landed.

After that, Niven received counseling and the support of a supervisor, who told him what every employee in pain wants to hear: I got your back.

###

If you are having suicidal thoughts, you can get help from the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE