Handle With Care: Jason Lopiccolo with a couple of his finished knives | Photos: Andrew Goff

There is never going to be a shortage of makers in Humboldt County. There has always been a lot of value in the arts and crafts community at large.

Jason Lopiccolo, 38, is a full-time biologist and part-time high-end knife maker. At his day job for The Watershed Stewards Program, Lopiccolo is writing, analyzing data and helping onboard young scientists for a 10-and-a-half month program at various California sites.

After clocking a 40-hour work week, he devotes 25-30 hours of his remaining time to knife-making.

“You make time when you like doing something,” Lopiccolo continued. “I don’t know how long I can keep making it work as someone who produces knives.”

Above and below: Some of Jason’s finished products | Instagram

Lopiccolo makes his knives in his backyard

There are several ways to get your hands on one of Jason’s knives. You can find his available knives at a local vendor’s markets. You can work through a specialty cutlery shop in Sacramento. Or you can contact him directly through one of his various online avenues — via email, Instagram or his website.

At one point Lopiccolo did make direct sales through his website, but since he cannot keep things in stock regularly he refrains from using it anymore. In any case, roughly 60 percent of his sales are local and the rest are online, throughout the United States.

“It all started because I needed to do something with my hands,” said Lopiccolo.

Ten years ago, before forging with hot metals, Lopiccolo earned his bachelor’s degree in biology. In that time, he always worked and still needed to take out loans. He worked full time as an algal culturist growing microalgae for an oyster hatchery and also taught lab courses in various subjects (Invertebrate Zoology, Phycology, Intertidal Ecology) at Humboldt State while he finished up his master’s degree.

Ever since his arrival in Humboldt County, Lopiccolo hustled at his multiple jobs to pay his bills. Once his knife-making took off, it helped supplement his income enough to stay afloat.

“You’re surviving, but you’re sure as hell not thriving,” Lopiccolo said.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Lopiccolo lost all forms of work, leaving him unemployed for six months. In that time, knife-making kept a roof over his head until he was hired for his current gig.

He wasn’t always good at it.

Lopiccolo was introduced to wood-spoon carving by his mother. She wanted all her children to make her wooden spoons for her 50th birthday. Lopiccolo really took to it. So much so that he would hold get-togethers called “Whittling Wednesdays,” where people went over to his house to carve spoons into the evening. He enjoyed it so much that it was the primary activity at his bachelor party.

It became the his gateway to knives.

“One summer I had spare time. On a lark I bought a cheap-o forge online and started hammering away,” Lopiccolo said. “My first knives were intended for spoon carving, and then I started making kitchen knives.”

Lopiccolo describes the first few knives he made as generally terrible. He learned, made mistakes, then made something decent and started selling a few. The very first knife he sold was around $40.

It began with a few posts on his personal Facebook page. People began to talk. Then he was approached by the Bayside Grange to start selling at one of their tables, there. After accepting their invitation, he got some more interest. From there, j.lopiccolo_blades on Instagram picked up the momentum and made him a local talking point.

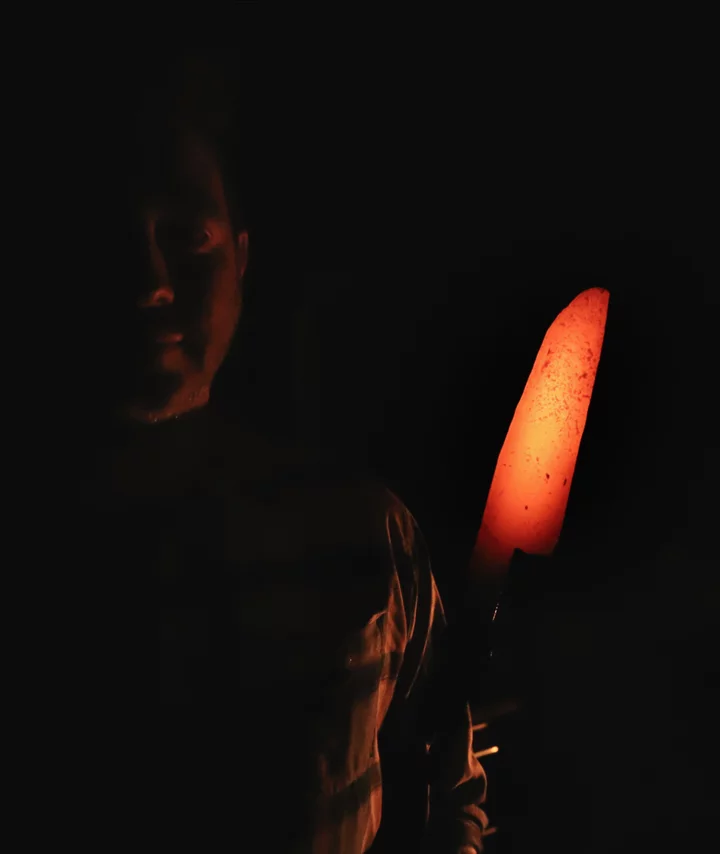

Making beautiful knives takes patience. Above, Lopiccolo heats his metal in a propane forge. After the steel is glowing and malleable, he carefully uses tongs to extract it from the forge then uses a combination of a 12-ton hydraulic press and a trusty anvil and hammer to shape the piece. This process is repeated until the shape is to his liking.

An unfinished Damascus steel knife blank ready for grinding

Some knife handle options

Typically he makes batches of knives roughly ten at a time. Each one takes about 12 hours total to make. It has not been in any way profitable, but it has sustained itself. It’s obvious that Lopiccolo loves his craft, and most of the cost of each knife is to recoup the cost in materials and the time it took to make.

Sourcing the materials adds to the length of his process, but we live in an area that has plenty of beautiful woods to make handles out of, the most popular being redwood burl. There’s always a story to each piece that Lopiccolo works with.

Whenever he travels, he manages to bring home some new wood to craft with. While in Norway for his honeymoon — he’s married to Supervisor-elect Natalie Arroyo — he was given a block of birch that would not fit in his luggage. Determined, he pulled over at a gas station, bought a saw, and sawed the block of wood into pieces that would fit his luggage.

At the most recent North Country Fair in Arcata, one of his knives sold for $600. The most expensive knife he’s sold so far was just under $1000.

“I eventually made enough money to buy a digitally controlled kiln,” Lopiccolo continued. “It was probably the most important thing I could have done.”

Lopiccolo thinks of himself as a perfectly competent bladesmith, but wishes that he could pay to get some of his first knives back. Mostly because he thinks they are awful, but there is a little nostalgia behind it as well. He also considers offering to make newer, better knives for those people, but they are not interested in giving them back. They either gave them away as gifts or they now have their own sentimental value.

Your average home cook does not need the sharpest, most expensive knife. Those things don’t make it special. A local maker that spends hours crafting a unique, one-of-a-kind daily tool is special.

Lopiccolo knows it, and so do his customers.

“I never want to be a full-time knife maker.” Lopiccolo said. “ I think it would take the joy out of it.”

###

CLICK TO MANAGE