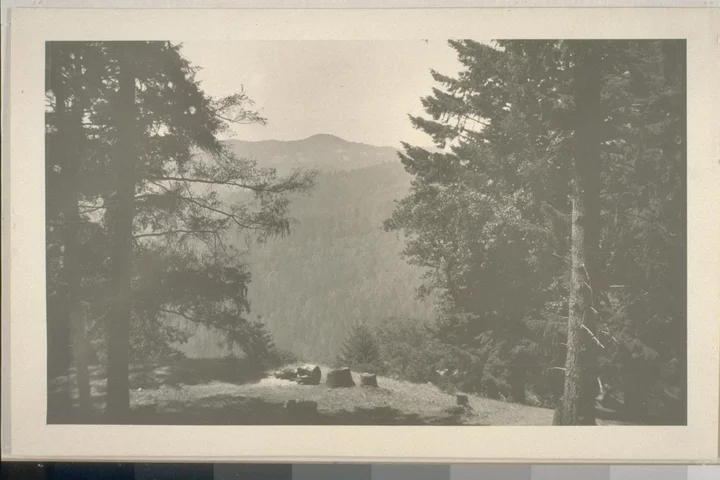

The South Fork of Dobbyn Creek, in Lassik Country. From the C. Hart Merriam Collection of Native American Photographs, via the Online Archive of California. Public domain.

Of all the thousands of Native Americans who lived in Humboldt County during the 1850’s and early 1860’s, one of the most often heard names was that of Chief Lassik.

His renown was such that several prominent landmarks were named after him (Red Lassik and Black Lassik Peaks) and the tribe of Indians to which he belonged was called the Lassik. His name also appeared in several Army reports and newspaper articles between 1860 and 1862. Even though he was Lassik and mentioned in the surviving literature as much as any other individual Indian during the time of the northwest California Indian “Wars,” we know surprisingly little about him as an individual.

Nothing of Lassik’s childhood was ever written down. There is some indication that he may have been part Wintun (the Indian tribe to the east of South Fork Mountain). In any case, he apparently grew up in the area comprising the head waters of the Mad River westerly to the present town of Garberville.

To understand who Chief Lassik was it is necessary to know something of who the Indians of Southern Humboldt were and how they lived. The Lassik tribe to whom Chief Lassik’s name became attached spoke an Athapaskan language distantly related to other Athapaskan languages, such as Navaho and Apache in the Southwest, and most of the native languages of Western Canada and parts of Alaska. Other speakers of California Athapaskan languages were the Hupa, Chilula, and Whilkut to the north of the the Nongatl, Wailaki, Sinkyone, Kato, and Mattole of southern Humboldt County and northern Mendocino County. The Lassik were closely related to their neighbors the Nongatl, Sinkyone, and Wailaki who spoke related dialects the Lassik could understand. It is with these neighboring Athapaskan groups as well as the Wintun to the east that the Lassik had the most dealings in the form of trading, intermarriage and warfare.

Lassik territory was abundant in food and other natural resources. To best utilize this abundance, the Lassiks practiced a more or less nomadic lifestyle within their territorial boundaries, moving around to be at the right place when important seasonal foods became available.

During the early fall, the acorns ripened and groups of Lassiks camped near the acorn groves to harvest this important food. The coming of the first heavy rains brought the critical late fall salmon run and the Lassiks moved to camps along major streams. The Lassiks relied upon these staples (acorn flour and smoked salmon) to make it through the lean winters. They were proficient hunters and gatherers, and starvation was rare. During the spring, clover and other fresh greens were gathered while grass seeds and grasshoppers formed an important food in the summer. Deer, elk and other game animals were hunted throughout the year.

The structure of Lassik society was characterized by a greater amount of looseness and fluidity than that of other more structured and settled groups, such as the Yurok and Karok to the north and Pomo to the south. Although little is recorded on Lassik social organization because most of the tribe had been killed by 1865, it is known that the family was by far the most important social unit. Village bands consisted of several loosely bound family groups sharing a winter site. The village was not a land owning entity. Very limited areas, such as house sites, acorn groves, or good fishing spots were the only kinds of real estate which may have been claimed by individuals or families.

Other lands within the territory claimed by the tribe seem to have been used in common by all members of the tribe. Trespass by outsiders was serious business and uninvited members of other groups were often killed when caught.

Although political leaders existed among the Lassik, these headmen or chiefs were not necessarily hereditary. They were chosen for their wealth, skill in solving disputes and wisdom. They were not absolute rulers, but made suggestions which were followed or not followed depending on their popularity and the consensus of opinion among the group. If an individual or family didn’t get along with the headman of their band they simply moved and lived with another Lassik group. Chief Lassik must have had some excellent leadership abilities because he apparently was recognized as a headman by most, if not all of the Lassik village groups.

Lassik’s chieftanship saw the fortunes of his people go from good to nonexistent. He had the misfortune to be the leader of his people when southern Humboldt County came under the “civilizing” influences of white pioneers. The incoming white settlers did not understand the Indian lifestyle nor did they accept Indian ownership of land by the rights of prior possession.

Most Euro-Americans of the mid-1800’s were not tolerant of cultures other than their own. There is a strong correlation between racial intolerance and feelings of insecurity, as one causes the other. The early white settlers certainly felt insecure about the Indians when they came to Humboldt County because the Indians at first outnumbered them. In addition, the pioneers arrived with strong traditions of getting rid of Indians in one manner or another. They thought the Lassik hunter/gatherer existence made an incomplete use of the land and strongly believed in the idea of “Manifest Destiny” that chosen Caucasians could take over the land.

One writer familiar with the Indian/white situation in southern Humboldt wrote of the problem as follows:

“When the white settlers took possession of the nicest valley lands and crowded the Indians into the wilderness with a warning not to invade the white enclosures, the natives were left without means of sustenance. There was nothing for the Indians to do but to prey upon the white man’s flocks, herds, and crops. Of course they did it. ” (William Roscoe)

The raising of beef cattle was the principal means of income for many of the settlers in the southern Humboldt area. These pioneer whites arrived anticipating rich returns from the establishment of a cattle industry. Prices for beef during the late 1850’s and early 1860’s were high, and a ready market was available in the mines and fast growing cities of northern California.

The killing of stock by Indians evoked immediate and harsh retaliation from the stockraisers because such “depredations” hit the whites where they were most sensitive — in the pocketbook. A pattern soon became established that when cattle were killed Indians were killed.

We don’t know what Chief Lassik was doing during the earliest years of the white settlement because his name is not mentioned until the Lassik began resisting the white encroachment and killing around 1860. What little is written of Chief Lassik during the years from the start of the Indian-white hostilities in southern Humboldt around 1860 until Lassik’s death in the winter of 18621863, comes to us from contemporary white sources which were invariably anti-Indian.

Lassik is described in various military reports and newspaper articles as terrorizing southeastern Humboldt County, committing numerous depredations and stirl-ing up discontent and revengeful feelings. In all these reports however, there is not a single specific example given of any robbery or killing to which Lassik was known to have been directly involved. He is merely condemned in general terms and labeled as a leader of a “predatory band.”

There is little doubt however, that Lassik did take an active role in resisting the white takeover in his land. He is credited with leading raids on the isolated settlements within his territory, which although resulting in few white deaths, drove the settlers out for a period of several months. These actions were described as foul murders and depredations by the Humboldt Times. It is an established pattern throughout time, however, that history is written by the conquerors and those considered criminals by the victors are often considered freedom fighters by the oppressed. In any case, the Lassik culture and Chief Lassik himself were doomed.

In July of 1862, Lassik was brought in with thirty-two other members of his surviving band and we get a brief and insufficient first hand account of him. He was taken to Fort Humboldt and. then to the holding area for Indian prisoners on the Samoa peninsula. There he was visited by the editor of the Humboldt Times who reported, “In looking through camp we noticed the somewhat noted chief, Lassac. He was stubborn, and would not speak.”

In August, the Indian prisoners on the peninsula were removed to the newly created Smith River Reservation. Conditions at the reservation were typical for Indian reservations at the time—in other words, appalling. Joe Duncan, who was a Mattole Indian, was taken to Smith River at around the same time and reported later on the conditions as follows:

“White man take Indian Smith River Reservation. Indians go. White man make ‘em work; work for white people. Women, children, everybody make ‘em work. That what white man did. Keep him down, Indian people. Three men boss, go round and make ‘em, work; make plow. If he go slow, kick him, hit him club, kill ‘em right on road. Government all right. Government send grub, blankets, clothes. Agent sell on road. Government don’t know. ” (C.H. Merriam)

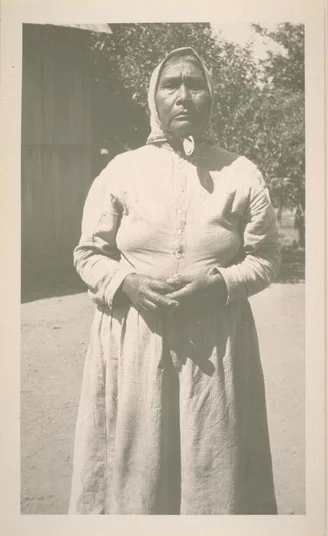

Lucy Young, cousin of Chief Lassik. Public domain photo via the Online Archive of California.

By September 24th Lassik had escaped from the reservation with much of his band and in an incredible journey made his way back to his traditional home within a month. His freedom was short lived, however, for in late December of that same year he, along with three men and five women, were apparently tricked into coming to Fort Seward which was at that time a center for the Indian slave trade.

It was here that Lassik died and it was here that we get the only account of words he supposedly said. As Lucy Young, who was Lassik’s cousin and already staying at Camp Seward at the time recounted:

“I go on to house. Everybody crying. Mother tell me “All our men killed now. ” She said white men there, others come from Round Valley, Humboldt County too kill our old uncle, Chief Lassik, and all our men. Stood up about forty Inyan in a row with rope around neck. “What this for?” Chief Lassik askum. “To hang you, dirty dogs, “white men tell it. “Hanging, that’s dog’s death,’ Chief Lassik say. “We done nothing to be hung for. Must we die, shoot us.’ So they shoot. All our men. Then they build fire with wood and brush Inyan men been cut for days, never know their own funeral fire they fix. Build big fire. Bum all bodies…”

Thus ended Lassik’s life. In the same issue of the Humboldt Times (January 3, 1863), the editor, Austin Wiley, reported on the arrival of Captain Henry Flynn at Fort Baker. Wiley wrote, “…if we are not badly mistaken in the man he will deal with Indians when he finds them according to the system of Indian fighting which we in this country think is right.”

This system was to kill all the male Indians when found and take the women and children prisoners. Many women and children were reported killed “by mistake.” The surviving Lassik Indians within their traditional territory were hunted down, and the men hanged or shot. Many women ended up as wives or concubines of white settlers, and many of the surviving children were sold as slaves in Sonoma County and parts south. Although the Lassik became extinct as a viable culture, many people living in the county today are part Lassik, so the group may be considered as surviving through their numerous descendants.

###

The story above was originally printed in the March-April 1985 issue of The Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society, and is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE