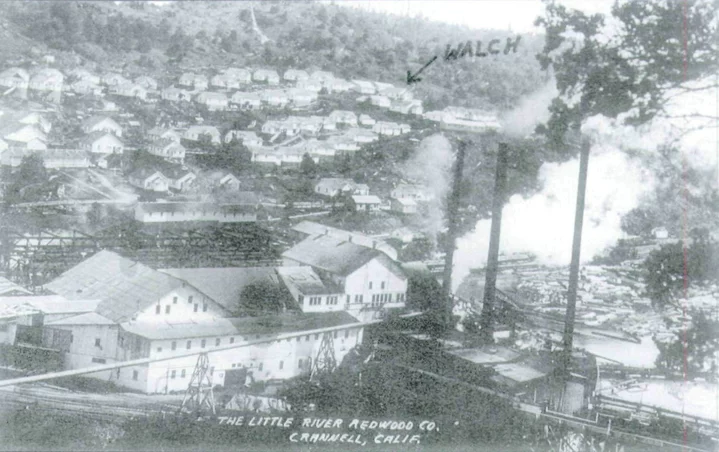

The bustling lumber town of Crannell, with the Walch house indicated. Photo courtesy Wes Walch, via the Humboldt Historian.

At the time of my birth, on December 10, 1928, to Weston and Mary Walch, a winter storm caused Little River to overflow its banks, flooding the valley and the road between Highway 101 and Crannell. My grandmother, Mae Fields, had driven up from Eureka in her high-wheeled Buick Roadster — the only car in our family — in order to take my mother to the hospital, but soon after her arrival at our home it became impossible to drive into or out of Crannell. The floodwaters were rushing over the road and the only way to get to Crannell was by the company railroad. Dr. Cooper, from Arcata, agreed to attend the delivery at our home, and my dad arranged with Mr. Heightman, the town boss, for an open-sided railroad car, or “speeder,” to bring Doctor Cooper into town. That was a cold and wet ride above the flooded road to Crannell. My mother was already in labor and Dr. Cooper arrived just in time for my birth. It was an adventure for the doctor to come as he did through the storm that night, and it seems it was an omen: my life was meant to be an adventure.

Crannell was a railroad logging “company town” owned by Hammond Lumber Company. The town was complete with family housing, bunkhouses and a lodge for the single workers, a cookhouse, company store, grammar school, church, a firemen’s dance hall and other facilities for the workers and their families. Crannell was located ten miles north of Arcata and two miles east of Highway 101 and Clam Beach. Little River coursed its way from the redwood-forested hills above Crannell, down beside town, then through the valley and the dairy-farm bottomlands, to flow into the ocean near Moonstone Beach.

Crannell on the map.

When I was born my parents already had three daughters. My dad had always been an outdoor person. He’d grown up on a ranch, he hunted, fished, and worked in the woods, and he wanted a boy. As told to me by my mother and grandmother, when my dad saw that I was a boy, he grabbed the doctor and danced with him on the kitchen floor. 1 had three older sisters, Belva (Dinah), Mae Pauline, and June Ann to dote over me, and I grew up in a very loving family.

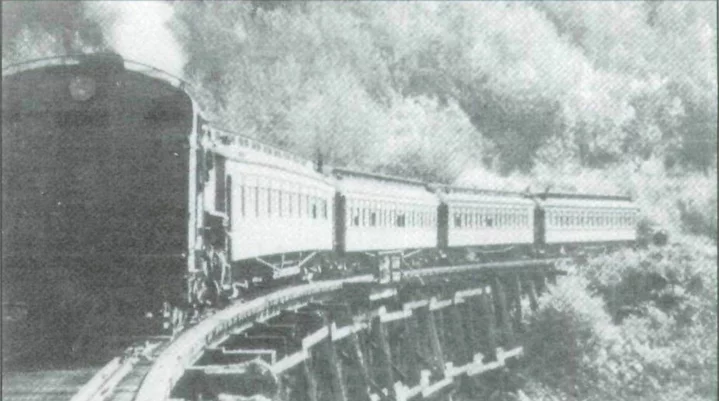

My very first memory in Crannell is of the train whistle each morning at five o’clock to awaken the workers for breakfast. After breakfast the loggers and woods crews would hike up the hill to the station and take the train into the woods for another day’s work. Ken Cole, or another of the Coles, was the engineer. The train would leave the roundhouse at Railroad Avenue and make its way up to Little River Junction, across the curved high trestle, and loop around to the upper, east side of Crannell, where we lived. The east side was called Hillside Terrace, and the lower, west side was called Eucalyptus Heights. Fancy names for this little town of Crannell! As the train neared the area above our house to pick up the crews, it would let out another whistle blast. Hiking from their homes to the station and back, the loggers cut deep trails with their caulk boots over the years, some more than a foot deep. Bachelor workers ran down to their cabins after work to be first to get hot water for a shower, and first in line for the dinner bell.

Passenger train hauling crews to the Hammond woods, 1930s. Photo courtesy Jack Trego, via the Humboldt Historian.

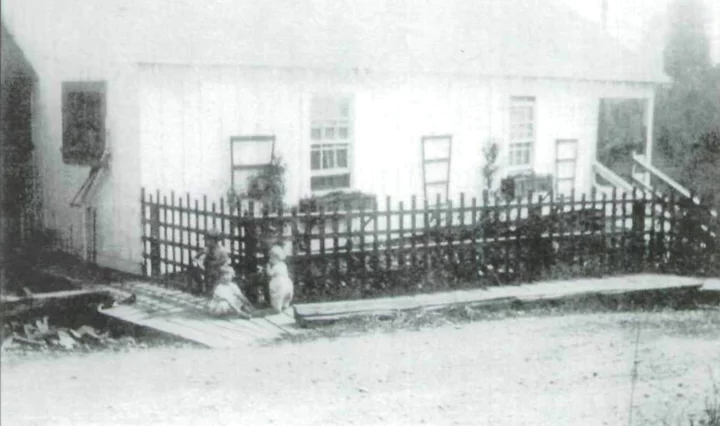

Our house on Hillside Terrace was the last house up the hill, not far from the upper tracks, and the steam whistle sounded like it was right outside our windows. We were close friends with the Cole family, and Ken Cole would always give a couple of toots above our house when he brought down another trainload of logs.

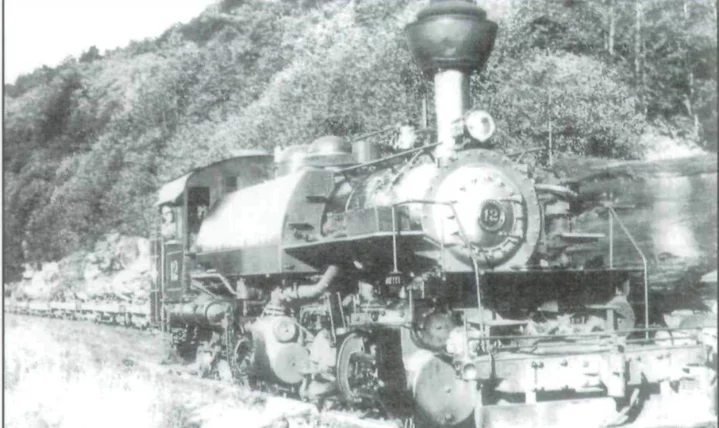

In addition to the passenger train, there were six other locomotives that pulled strings of flatcars to the woods. The caboose, with its potbellied stove, made a nice warm place for the crew to eat lunch or play cards while waiting in the woods for the flatcars to be loaded. Once loaded, the flatcars would be pulled to Crannell and left on a siding. A much larger locomotive would then pull two or three of them at a time out to the big company sawmill in Samoa. The railroad grade from Crannell to Samoa was mostly flat. It ran along the sand dunes of Clam Beach, over the Mad River railroad bridge, then on to the Samoa mill. Upon returning to Crannell the locomotives would be aligned in the roundhouse into proper work stalls by a large turntable. Night crews would apply oil and grease and make repairs, readying them for another day’s work. All day long during the work week, railroad trains were chugging and whistling past our house in Crannell.

I will always remember the sounds from these trains — the steam from the locomotives, the shrill whistles, the click-clack of the wheels on the rails and the screeching sounds of steel wheels against steel tracks when the trains rounded a curve. I can still recall the smell of the pungent black smoke belching from the stacks as the trains pulled hard up the railroad grades. These trains and the railroad were in use until the big 1945 fire in the Hammond logging woods near Big Lagoon, which burned down twenty-three bridges and destroyed much of the railroad.

Ken Cole with a load of logs for the Hammond mill at Samoa, 1930s. Photo courtesy Clearman Cole.

The beginning of my life coincided with the beginning the Great Depression. As everywhere. Depression times were tough in the timber industry. Due to the low demand for lumber to build houses, logging crews were working only a three or four-day week, and only one in three neighbors had work at all. My dad was fortunate to have mostly steady work during the Depression, as his job was operating a railroad steam crane. The high boom steam cranes were necessary to lift big timber beams to build the railroad bridges and to clear out mud and rock slides on the railroad tracks during winter storms.

The author, Wes Walch, with his sisters, Mae Pauline, Belva, and June Ann, in 1933. Photo courtesy Wes Walch, via the Humboldt Historian.

Even after the Depression, money was still scarce for my family and most others in Crannell. I do recall as a child my parents and our neighbors playing cards and drinking homemade beer that my dad and most of the men made. While the men played pinochle in the dining room, the ladies played Parcheesi in the kitchen. I remember this because my small bed was next to the wall in the dining room, and I would fall asleep with my dog Poochi lying beside me, listening to the men talking and laughing at the table.

Such get-togethers and the Saturday night dances were the entertainment in those days. And we did have a big cabinet Philco radio. Whenever President Roosevelt would give his weekly radio talks to the nation, all the grownups tuned in, listening to his every word. All of us kids would have to be quiet and not make a sound when President Roosevelt was on the radio.

Even when our folks had very little money, we always had plenty to eat. My dad raised chickens, geese and rabbits, and we had a big garden. When old enough I helped my dad spade and plant the garden and my sisters kept busy picking the vegetables and helping our mom with the canning. Deer, ducks and fish were always plentiful, and it was pretty much open season all year round if you needed meat. Most of our fresh fruit and corn came from Pepperwood and Shively. My grandmother would bring boxes of corn, peaches, pears, apples and other fruit for canning. We had a large room next to our woodshed with shelves of canned food. The milkman and butcher wagons delivered milk, eggs and meat around town. Milk came in thick glass bottles and you could see the cream on top. If we were out by the meat wagon and hung around long enough, we could almost always get a beef wienie from the butcher as he made his rounds.

My mother was an excellent cook. Her parents, Josie and Nick Dubrovic, emigrated from Vienna, Austria and settled in Arcata. Grandfather Nick was a ship’s carpenter and he built a large two-story house at 15th & G Streets in Arcata for their large family of four girls and three boys, with extra rooms for boarders. On weekends, bachelor workers When old enough I helped my dad from logging camps and sawmills would come into town by train and board at their home. My mom grew up helping to cook for these boarders, and she also worked in her late teens as a waitress and cook in a cookhouse. She enjoyed cooking and in addition to Austrian dishes, she made delicious soups, including her specialty, Italian minestrone. Mom made her soups in large cookhouse-sized kettles, and all were welcome. On occasion, there would be over twenty kids at our house eating her soup.

The town of Crannell was a close-knit community. It was a standing joke around town that the ladies auxiliary did all the firefighting. The men would be out working in the woods during the day and the ladies auxiliary would put out the fires. The PTA met once a month at the schoolhouse, bringing potluck meals. My mom usually brought delicious kettles of tamale pie. The volunteer firemen put on town dances, for which they provided the midnight meals. Built on steep-sided hills that ascended from the valley and Little River, Crannell comprised 125 homes, with about 450 residents. Water came from several springs above town, with small reservoirs that fed into three or four fifteen foot by twenty-foot tanks. Three-inch metal pipes carried the water into town. The roads were all gravel; only the road from Highway 101 up to the company store was paved. Sidewalks, picket fences, and bridges were all made from redwood boards or timbers.

The author’s father, Weston Walch, standing on the boom of the steam crane, 1930s. Photo courtesy Wes Walch, via the Humboldt Historian.

All workers’ houses were pretty much alike. Rent was $12.00 a month for each family and an extra $2.00 for a garage. For the bachelor workers living in the bunkhouse cabins and lodge, rent was free. Houses were made with 2x4-inch studs, and 1x10-inch redwood board-and-batten siding, supported by redwood beams. Our house, like many, was built on a hillside, with the lower end some ten feet off the ground. The space under the house was used for storage and, of course, for keeping the beer vats. The inside walls were 1x10-inch redwood siding covered with cheesecloth and wallpaper. The floors were covered with bright linoleum. All houses had wood cookstoves with hot water coils and pipes that ran to the hot water tanks, standing in the kitchen corner. The tanks were not big enough: hot water to wash and bathe was a scramble for us all. Each house came with two bedrooms, one bathroom, kitchen, pantry with a cooler {no refrigerators), washroom, living and dining room, and an attached woodshed off the back porch. My parents slept in one bedroom, and until we added a third bedroom, my three sisters slept in the other bedroom, and I slept on my cot in the dining room. Our mother would get up at 5:00 a.m. to light the stove and heat the water, make lunches for my dad and us four kids, cook an early breakfast for my dad before he went to work, and then for my sisters and me before we left for school.

I still remember an almost tragic morning when I was about five years old. I was up early for breakfast with my mom and dad, and there was a flock of quail in our garden. There were no houses above us so my dad would occasionally shoot quail that strayed into our garden. He was loading a 12-gauge shotgun in the kitchen, with the barrel pointed down to the floor, while keeping an eye on the quail. Suddenly the gun went off, shooting a two-inch hole through the floor. I was standing beside him and the shot missed my foot by just six inches. His face went white. He put the shotgun away and never attempted to shoot quail around the house again.

From our house up on Hillside Terrace we probably had one of the best views in town — to the ocean on the west, up Little River to the east, the forest to the north, and the valley and bottomlands to the south. Being in the last house up the hill also meant we had the longest walk, or run, to school, as well as to the store and down to the river. This turned out to be a good thing in a way, because my sisters and I learned to run very fast. We always won money in the foot races at company picnics and at the Mattole River BBQ’s on the Fourth of July. Our dad was fast, too, and would win the men’s races. He also played baseball for the Crannell team when they were in the mid-county league. He was a left-handed batter. In one game, at Scotia Lumber Company, he hit four home runs over the short right-field fence and into the Eel River

The general manager’s house was located on the hill next to the school with a view to the Pacific Ocean. The managers’ houses were much larger, with fireplaces, three bedrooms, two bathrooms, and hardwood flooring, picture windows and fancy kitchens. These houses also had steam heat from the steam boilers, left from the days when the sawmill was in Crannell. Growing up, it was quite apparent to me that the managers and bosses had the best houses and all the perks. 1 knew then that, someday, I wanted to be one of those bosses.

The company store stood in the hollow between Hillside Terrace and Eucalyptus Heights.

Crannell store in the 1930s. Photo: Walter Warren collection at CPH, via the Humboldt Historian.

It was a large two-story building containing a department store, groceries, a meat market, and the towns post office, with individual boxes for residents. All produce and merchandise came in by railroad to a siding at ground level, and was carried to the upper floors on a large platform elevator. Mr. Gregory was the store manager. One hand-lever gas pump stood outside the store, as well a phone booth containing the only public phone in town. If we wanted to call someone we walked or ran to the store and waited our turn, as the phone was generally in use. Since it was on a party line, the calls were none too private anyway.

At one end of the store were the offices for the woods managers, safety, and payroll. It was at a sliding window between the offices and the store that one could obtain scrip money. You know the tune, “You Owe Your Soul To The Company Store,” by Tennessee Ernie Ford? Hammond Lumber Company had its own scrip money — from a copper dollar down to a penny — and each coin had an H stamped through it. If a worker was short of money before payday, he could go to the store payroll office and borrow scrip money. Of course, you could only spend the money at the company store and the company would deduct what was borrowed from your next paycheck. There was a lot of Hammond Lumber Company scrip money borrowed in those days. and many who owed their souls to the company store.

Next to the store were a barbershop, the bachelor men’s cabins, a one-room library, and the large busy cookhouse. The company cookhouse fed the bachelors and management personnel. Each day head cook Tony Gabriel and his wife and staff prepared a large breakfast of pancakes, eggs and meat for more than 75 men, a box lunch for the woods crew, and a big dinner that always had two or three choices of meat, potatoes and gravy, vegetables, and choice of pie or cake. Cookhouses were famous for their well-prepared and large meals to satisfy a hungry logger and had their reputations at stake to attract good steady workers.

Workers paid about thirty dollars a month for all their meals. Tony Gabriel was a great cook as well as an excellent baker, having studied and worked as a chef in hotels in Chicago, before coming out West. Tony would often have large cookies or a piece of fried chicken for us kids when we came by after school.

The Walch house in Crannell. June Ann, Mae Pauline, and Wes Walch, 1929. Photo courtesy Wes Walch, via the Humboldt Historian.

The company raised its own pigs in large pigpens east of town. Pork chops, roasts, ham and bacon for the cookhouse all came from these company pigs. The company garbage truck picked up scraps of food from the cookhouse and delivered it to the pigs on a daily basis. Seagulls gathered around the feeding troughs by the hundreds. From our house we could see these seagulls flying around and knew it was feeding time. The garbage truck also picked up everybody’s garbage on a weekly basis, a service included in the rent. The garbage dump was a good place for us boys to sharpen our shooting skills: we would plink at scurrying rats and shoot tin cans with our .22 rifles.

Across the river, down on the flat below the store, stood the Firemen’s Hall. The little non-denominational church stood beside it. Our sister, June Ann, was the first bride to be married in this little church and possibly the only one. The Firemen’s Hall, complete with kitchen, hosted meetings for the volunteer firemen and the Boy Scouts, as well as school plays, movies, and dances. Most folks didn’t have cars in those early days and the Saturday night dances were the big event. Everybody went, grown-ups and kids, and danced to Crannell’s own band, “Coles Californians,” led by Ken Cole. When us kids got sleepy we just lay down on one of the benches and went to sleep. Sometimes there was a little more than just dancing~a few too many beers and the fighting would start. I remember Dad coming home more than once with a bloody shirt. As recounted by my sister Belva, this would be the night that mom would make a rather lumpy bed in our large wood box just inside the back door for Dad’s discomfort.

Another big event was the Fourth of July, when Hammond put on a big picnic as a get-together for its two towns, the logging town of Crannell and the mill town of Samoa. The company transported the Crannell families out to Samoa for the picnic, twenty miles distant, on the logging crew train, and back home again that night.

BBQ beef and beans were served, with kegs of beer for the men, and soda pop for the ladies and kids. There were softball games, races for the men and kids, a tug-of-war between the loggers and the mill workers, and in the evening a dance at the Samoa Firemen’s Hall. This picnic was supposed to be a friendly get-together, but the competition coupled with the beer generally resulted in some pretty good all-out brawls between the loggers and the “sliver pickers,” which was what the loggers called the millworkers. My pal Ken Gipson’s dad, Cal Gipson, was one tough fighter and could hold his own at the dances and picnics with the best of them. My dad always claimed that he was just trying to separate or stop a fight and of course got right in the middle of it. I don’t know if it was because of the fighting, or lack of interest after people started getting cars and traveling more on holidays, but the company stopped having these “friendly picnics.”

###

The story above — an excerpt from Weston Walch’s book Growing Up in Crannell — was originally printed in the Summer 2009 issue of The Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society, and is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE