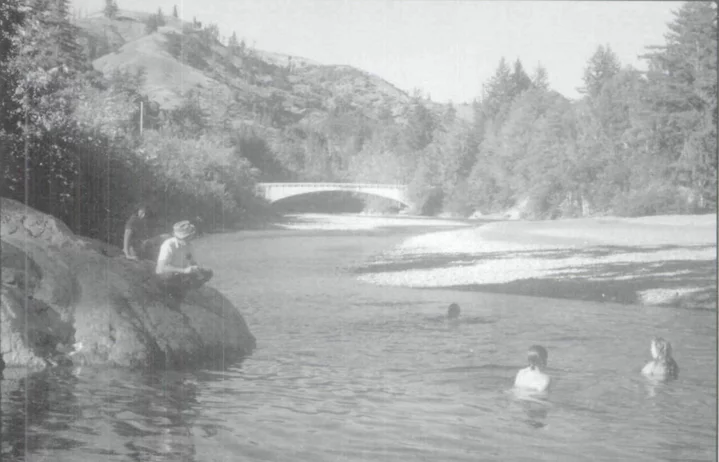

Swimming in the Mattole, near the Mattole Bridge at A. W. Way County Park. All photos courtesy Gerald Beck via The Humboldt Historian, unless otherwise noted.

There had been casual discussions over the past few years about the possibility of a visit to the Mattole valley, but the talk never seemed to evolve into a plan of action. At a recent dinner party, though, that barrier was broken and my friends rather unexpectedly said, “Let’s go!” As we climbed the “Wildcat” out of Ferndale on our way to my family’s camp on Conklin Creek Road, the suggestion was repeatedly made that my information about that part of the county ought to be recorded before it fades into the unrecoverable past.

And so I am charging forth on the wings of family history, on the stories of earlier times told by my mother and father until their passing in 1963, and on my own personal visits to the Mattole commencing around 1939.

My mother, Cora Farnsworth, was born in Ettersburg on the Upper Mattole in 1901. She had nine siblings. She graduated from the Petrolia School around 1912, and I have a photo from that time. It shows her standing on the school porch with the other students and the teacher.

The author’s mother, Cora Farnsworth, is in the back row, second from left. Circa 1912.

She often spoke fondly of a little black mare that she and her sisters rode to school. There must have been a one-room school in Ettersburg at that time. Her father had apparently come into the Upper Mattole with one of the earliest wagon trains to reach that area. He is buried in tbe old Mattole cemetery on the knob just south of tbe Petrolia Store. His name, Farnswortb, persists among some of the old-timers who use it to identify a ridge to the north of the table that one crosses traveling the Mattole Road to and from Petrolia.

Learning responsibilities in homemaking very early, my mother occasionally traveled to nearby Briceland, where she worked as a domestic servant. It wasn’t long before she had made the two-day journey by horse and wagon to Eureka, where she had gained employment as a clerk at Hink’s department store, which later became Daly’s.

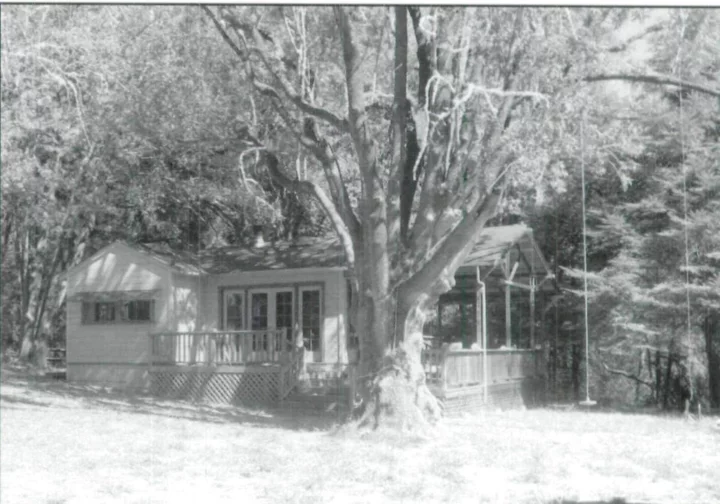

It was, however, the Mattole Valley that always remained in her heart, and when the opportunity occurred to purchase a few acres with a cabin on the lower river near Petrolia around 1956, my dad threw economic caution to the winds and purchased the property as a family retreat. To my mother it was like coming home. My parents were acquainted with many of the original ranch families of the area: Roscoe, Clark, Hindley, Lindley, Oeschger, Etter, Lloyd Roberts, Ear] Schortgen, etc. (Ken Roscoe’s Heydays in Humboldt is a fascinating collection of humorous anecdotes, mostly from the Mattole). Both my mom and dad loved going there, often inviting friends to share in what they considered their good fortune. In 1958 my dad paid $25 for a unit of “farmer’s lumber” from the mill in Carlotta to build an additional shelter. He pieced the components of the structure together in our horse barn at Hydesville, loaded them on the old 1947 International, hauled them down to the valley, and assembled what has survived to this day as “the sleeping cabin.” Their vision for the future of the property was that it serve as a special meeting place for the extended families of my two sisters and myself, a purpose it has served well for over fifty years.

The Beck family cabin on the Mattole. The wrap-around porch was added together with a new foundation after the 1992 earthquake, which neatly deposited the house ten feet from its original location.

Some of my earliest experiences on the Mattole took place in the forties at another beautiful cabin on the little flat, up a gulch and just slightly downstream from the mouth of Conklin Creek. Tbe cabin belonged to two older ladies named Williams and Graham, one a widow, the other a “spinster.” At that time these women owned the ranch in Hydesville that was later purchased by the Fearrien family when Les first came there. My dad had entered a business arrangement with Williams and Graham involving their ranch property: he would seed the large front fields on the Hydesville table to subterranean clover in return for the use of the entire ranch for livestock pasture. The older ladies insisted that our family make use of the cabin on Conklin Creek Road anytime we might choose during those years. There were at least three other cabins on this little flat. One belonged to Adrian and Sue Chapin, who ran a dairy farm in Ferndale, and Marge and Rae Wright utilized another. The Wright family bistory is associated with the earliest valley settlements. It was at this cabin tbat I first slept on Mattole ground, went trout fishing and first encountered water snakes and pinch bugs in my swimming trunks at the close-by pools.

My dad spoke of his experiences as a young man driving livestock from the Mattole to markets in Eel River Valley. During our family’s trips to Petrolia he always identified the various ranches that the road passed through from Bunker Hill to Bear River, over Cape Mendocino and down the coast to Davis Creek. Many of these properties were initially developed by the Russ family and acquired names from legends and myths like Mazeppa and What Cheer, to comments on the prevailing weather such as Spicy Breezes and Windy Nip. These titles always called forth my father’s memories of trailing cattle over the ridges in wind that made it difficult to sit a saddle. The perpetual ocean wind along the coastal ridges was often a distinct actor in these stories.

Curtis and Olive Walker were close friends of my parents. They lived on the Walker Ranch, which was situated on an exposed ridge above the Zanoni Ranch. For many years, access into the Mattole was directly up Domingo Creek from the ocean, tbrough Zanoni’s and past the Walker gate over into McNutt Creek. The transition from the coastal environment, where all the trees branched to the southeast from the perpetual ocean winds, over the ridge into the more protected valley climate, always seemed like pure magic to me, symbolic of suddenly arriving instantaneously in a true “heaven on earth” for a boy. Mixed with that magic is a story my dad told repeatedly about Grandma Walker, arriving at the gate from a daylong stage journey. According to accounts, it bad been so windy that the elderly lady bad been thrown off her feet and had crawled hand over hand clinging to the fence about a quarter of a mile to make it home.

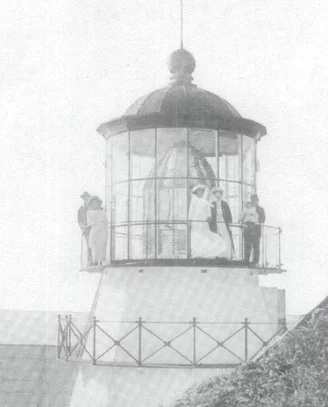

Thoughts of the Walker ranch bring forth my lifelong friendship with Curtis and Olive’s son Lowell. Redheaded Lowell was a couple of years older and a seasoned mountain ranch boy. One of my earliest encounters with Lowell was during a family visit to the ranch when he introduced me to archery. I think it must have been around 1939. Using Lowell’s bow and arrows out behind the barn, we took turns shooting straight up until the arrows disappeared into the wind and we ran for the barn to avoid being brained by the returning missiles. I was hooked and began begging my parents for a bow and arrows. Lowell had gotten his bow from the Cape Mendocino lighthouse keeper, who had fashioned yew wood bows for several years as a hobby to pass the solitary time. Finally, tired of listening to the begging, my parents took me out to the lighthouse to get me a yew wood bow.

What I recall about that day may be one of those little episodes that has expanded with time but it frightened me enough to stick with me for seventy years. The lighthouse keeper had suspended a ship’s hawser the short distance from his living quarters to the light so that he might go back and forth hand over hand to perform maintenance in all weathers. It was fair with a rather regular northwest wind over the cape that day as we got out of the car to walk down to the keeper’s quarters, but it kept me clutching the door handle of our little Ford. My father took one of my hands and my mother the other as they leaned into the wind to get down the trail. What I distinctly recall is a sensation of flying between and behind my parents because the wind kept me airborne behind them, my weight inadequate to allow my feet to touch the ground. I still the treasured bow acquired out on the cape that day, a reminder of a world of experiences.

The Walkers eventually moved to town where Curtis became a dairyman. He passed away as the result of a heart condition aggravated by a night spent attempting to save his milk cows from the rising waters of the Eel River during the 1964 flood. Lowell became a veterinarian and returned to purchase a ranch in the Mattole valley upon his retirement. The manned light house on Cape Mendocino was eventually replaced by an automated navigation light coded for identification by navigators. Over the years Blunt’s Reef was marked by an audible bell buoy and also by a manned light ship anchored on the reef, both now passed into history.

During our journeys to and from the cabin on the Mattole, my dad always had a string of tales concerning various points of interest along the way. Some came from have his personal experiences as a young cowboy in the twenties. Others related to the location and naming of stop on the early journeys from the various ranches and places. I learned of the early history of Bear River Valley and the original ranch families that first settled this tiny isolated community. It was interesting to realize that the old hotel at Capetown on Bear River was the primary stage stop on the journeys from Mattole country. It was a necessary facility because the trip took two days, at first by horse-drawn wagon that involved some segments of travel along the ocean beaches at low tides and required fording the Eel River. When the Mattole Road was developed, the stage always stopped overnight at Capetown. There were stories of waiting for low tides to herd cattle up the coast past the promontory that old timers refer to as Devil’s Gate, in order to avoid driving the stock up over the ridges at that point.

The changing perspective of Steamboat Rock was always fascinating to watch as we traveled past the cape. It was the stuff of seafaring fantasies for a ten-year-old, as were stories of a mounted cavalry detachment that was maintained on the beach between Devil’s Gate and Davis Creek during the years of the Second World War. Dad always pointed out the location of the corrals and barracks that had housed a small team of horsemen who patrolled the coast from the mouth of the Mattole to the cape. Their mission was to look out for Japanese submarines and foreign ships.

To remember the Mattole is to remember the joys of swimming and fishing. Early visits to the valley, before the acquisition of our cabin property, always meant daily swimming adventures in the nearby pools and a regular opportunity for trout fishing in virtually untouched streams. To a ten-year-old it was the best of all worlds. What could surpass sleeping out under the stars, awakening with a blacktail doe peering down at you, promenading to the river to swim, lunching on all your mother’s favorite dishes, and going fishing in the afternoon with trout for breakfast next morning. Heaven on earth!

The Mattole has been one of the very best streams on the entire North Coast for salmon and steelhead fishing. When I became interested in the larger fish, I often fished the river and learned of questionable harvesting procedures carried out at the river’s mouth. In a normal rainfall year the mouth would dry up, leaving a narrow spit separating the river estuary from the ocean. When it was determined that the runs were waiting offshore to travel upstream for spawning, it became common practice for a team of locals to open the mouth of the river by digging a narrow channel across the spit with shovels, to fork the numerous salmon out of the narrow channel with pitchforks and to haul away wagon loads of salmon. This was likely one of the factors contributing to the decline in fish populations. Another factor is probably the erosion and silting of the stream resulting from the years of unregulated logging. Modern efforts aim at preventing the anadromous fishes, particularly the Coho, from becoming extinct.

Looking down from Bear River Ridge into the Bear River Valley. The Petrolia Road is seen going past the Capetown Hotel and up the hill to Cape Mendocino.

The Mattole Valley has always struck me as a raw uncontrolled landscape of amazing wildness and excesses, such as the earthquake activity, the torrential rainfalls, rapid floods, wildfires, and lawless pioneering. Historically, there are areas of the drainage that have experienced frequent downpours in excess of ten inches in single twenty-four-hour periods, resulting in annual precipitation totals well over one hundred inches and rapid river flooding. Some of the original ranchers repeatedly set fire to their land with the dual purpose of eventually making the land produce more forage and exercising seasonal control of the noxious species and poison oak.

The younger generations currently residing in this area have accomplished clear changes in the social, economic, and cultural structure of the Mattole drainage. Laura Walker’s Mattolia gives a view of current residents’ perspectives about the valley. Current policies of fire control have changed the landowner’s management procedures. Seasonal uncontrolled wildfire is no longer a forage management option. A great deal more attention is directed at preserving the various aspects of the environment, including timber management, water utilization and restoration of the fisheries. The valley now sports day camps for kids and a high school. In earlier times, many valley youngsters were boarded out in Ferndale during the school year because of the time and uncertainty of travel in and out of the area.

Such symptoms of civilization, however, cannot erase the early history, the indelible string of boyhood adventures, and the later years of country experiences that feed my love for the Mattole River Valley. To this day I get up in the morning, go to the sink and splash cold water in my face, pretending it is water from the Mattole.

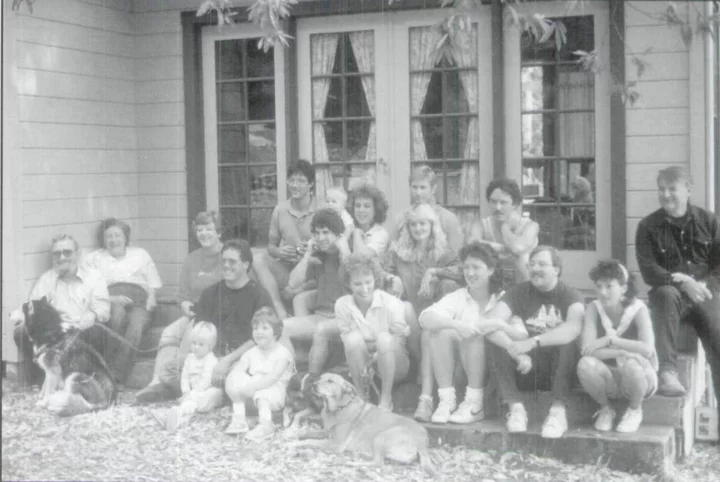

A Beck family reunion, circa 1985, with the author’s children, grandchildren, sisters, and nieces and nephews. The family continues to gather when they can at the Mattole cabin.

###

The story above was originally printed in the Summer 2011 issue of The Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society, and is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE