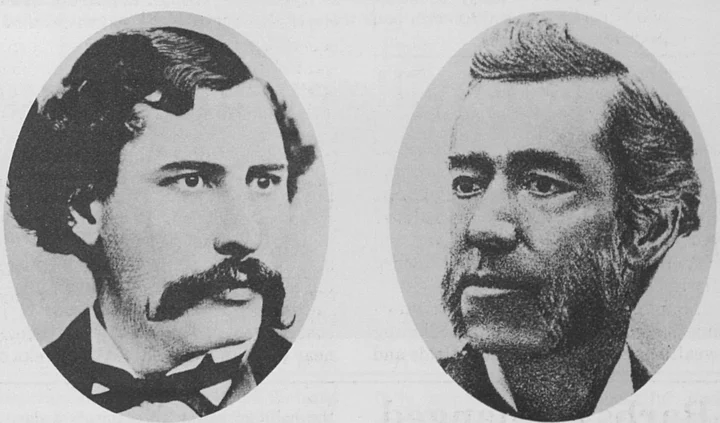

Bret Harte of the Californian (left) and J.E. Wyman of the Humboldt Times. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

California newspapers of the mid-1800s are filled with the “feuds and fussin’s” of their editors, which quite frequently led directly to a duel on the outskirts of town. And because the populace in the mining and lumbering back country was usually cut off from the mainstream of news, the editors in these smaller communities weren’t averse to making up their own. The resulting verbal broadsides and “art of repartee” were fondly appreciated by these pioneers.

One such encounter took place in Humboldt County in 1859 between the junior editor of the Northern Californian and the editor of the Weekly Humboldt Times. The Californian was published in Union (Arcata) by Colonel Stephen Whipple and came out on Wednesdays. The Times was published Saturdays in Eureka by A.J. Wiley and edited at times by J.E. Wyman, an attorney who had been a superior court judge and would, in 1864, become the owner and publisher of the Times.

The two newspapers had been exchanging verbal rhetoric over politics even before the arrival of 21-year-old F.B. Harte, a moody, restless young man who had a fervent desire to be a writer. Two of his poems were already in print, their language flowery. Through the intercession of his friend, Charles Murdoch, of Union, Harte was employed by Whipple as a printer’s devil and reporter in early 1859. He soon learned to pare down his words and developed a descriptive style that was all his own. But Harte found few friends in the community who appreciated his satiric wit.

J.E. Wyman was Harte’s exact opposite. A volatile, energetic man who was not averse to “having a drink with the boys.” he hunted down news wherever he could find it, either along Eureka’s rollicking waterfront or somewhere else in the county. His paper reflected the feeling which was prevalent throughout California on the government’s “extermination” policy — the annihilation of the California Indian population.

Near the end of 1859 Harte was put in charge of the Northern Californian several times by editor and publisher, Whipple. Harte’s writing reflected his newfound confidence, since several of his poems and writings had been published in the Golden Era, a literary publication based in San Francisco which appreciated his penchant for satire. Earlier in the year he had lampooned Whipple, who was said to be “dating” in San Francisco. Harte wrote a description of Whipple’s appearance, including mention of his large bouquet of flowers, and told about him standing in a “glassy-eyed” state before the window of a dressmaker’s shop. Wyman, in the Times, chortled, “Come home, dear Stephen.”

On November 26, Wyman printed in what he said was an answer to a subscriber’s letter, a proud report of Eureka’s thriving business concerns, listing the sawmills, saloons, hotels, leather shops, etc., adding there were also two doctors and a dentist. This was too good a chance for Harte to let pass, and he promptly wrote an account of the business in Union which, of course, lampooned Eureka:

Our neighbor at the lower “end of the bay” has written an account of Eureka. The subjoined “idea” of Union was conceived and projected some time since by a friend who expected to be written to on the subject. Owing to the mortifying circumstances of his not having received any request to that effect, he was not induced to hand us the same for publication. There seems to be a vein of levity under all his seriousness and a vein of seriousness substratifying his levity:

“Union is a country town remarkable for having been the birthplace of several of posterity. The inhabitants are intelligent and warlike. Education has revealed the necessity of ‘going in when it rains,’ for which purpose several houses have been erected, and about half that number will be built as occasion arises. The people of Union are in the habit of eating three meals a day, at which time bells are rung at the principal hotels. It may be remarked as a singular circumstance that the omission of bell ringing would not in all probability alter the regular habits of the people. Owing to the cost of living a majority of the people ‘board.’ All other kinds of lumber are profitable. There is one flour mill, one saw mill and several other mills in town. Most of the latter are used for grinding coffee. The Northern Californian originates here. Union is not the capital of the U.S., but possesses many interests of object to capital, and some capital objects of interest. The End.”

On December 3, Wyman replied in a piece entitled “Now and Then:” “Occasionally some very good things appear in the Northern California — now and then some very silly things. For instance, the ludicrous description of the business in Union…It was intended to burlesque a local item which appeared in these columns last week.” Wyman stressed that the article of the week before was really printed in a response to questions submitted by a subscriber, and he had the subscriber’s name on file should anyone want to see it.

But “we admire a joke,” continued the Times’ editor, “and fully apereciate (sic) the bountiful supply of wit, humor, classical language and poetry which flow through the columns of the Californian, but we would suggest to our neighbor the propriety of selecting subjects for the exercise of his cargo of sarcasm which are not calculated to increase local prejudices, too much of which already exists — more particularly at this time than any other should they be avoided.”

Yet not to be outdone in the rich field of sarcasm, Wyman had to add, “With all due respect for the enterprise and brilliancy of the Californian’s editor, and without the slightest reference to the poetical production on the outside of his paper this week, we would like to enquire why he omitted, along with the mills there which grind anything from flour to coffee, to mention the ‘machine which grinds out poetry’.” This referred to “Why She Didn’t Dance,” a poem that Harte wrote and printed on page one.

Why She Didn’t Dance

by Frank “Bret”Tell me brown eyed maiden, O, gazelle eyed houri.

Draped in gorgeous raiment, circumscribed in gingham

Round thy neck a coral, and from each auricular pendulous an earring;Sittest thou so lonely, white the dance voluptuous

Twirls its giddy circles, twines its coils fantastic.

Charming like a serpent to the gently witching, scrapings of the fiddle.Art thou sighing, sighing, for the “distant prairie, ” and the meek eyed heifer dormant in the meadow

Where thy fancy fondly drew the lacteal fluid from the class mammalia? “Or hast thou a passion, called by some, erotic.

Superimposed on man, by Love’s first faint induction;

Countest thou the petals of the rosy hours

Waiting for thy ‘feller’?”Raised her brown eyes softly, that reflective maiden.

Raised her sweeping lashes, like sable curtain.

From its crimson portals poured her honied accents

As she made me answer:

“I’ve jest sot and sot — till I’m nearly rooted,

Waitin for the fellers, dern their lazy picters.

Stranger, I’ll trot with ye, ef you’ll wait a minit.

Till I chawed my rawzum.”

Harte made sure two poems adorned page one on December 7. Then he reprinted the Times rebuttal and gleefully took it apart:

Then…and Now?

The article alluded to was simply a burlesque of a burlesque, and little befitting the Olympian majesty of such a rebuke. We give the dignified conclusion of the Times’ notice of Eureka, upon which our folly was based:

“Of the societies there are the Humboldt Library Association, one Lodge of Masons, one of Odd Fellows, and the Ancient and Honorable Order of E. Clampsis Vitiis.”

Was this a joke? If it were, the clown has no right to make a dignified personal issue with the ringmaster who cracks his whip and his joke at his fellow actor; still less has the editor of the Times any reason to use the cant of “local prejudice” as a shield in such an encounter.

We deem this explanation due to any whom we may have unwittingly offended. Our contemporary’s style we won’t criticise. We leave it to the higher law of etymology and syntax. Noah Webster might object to the exercise of any cargo, but Noah Webster, though an editor, was not a critic.

Reserving our wit for the peroration, in flattering imitation of our superiors, and in the hope of saying something that may combine “classical” learning, “humor,” “sarcasm” and “poetry,” we would remark that somebody’s article reminds us of a description of modern Pompeii —” A patched structure of mud and straw, remarkable as being erected over an ancient italic base.”

Wyman’s reply of December 10 reads: ‘ “… the apology of the Northern California of Wednesday last … is perfectly satisfactory to us — at least the part we can comprehend. We did not, however, expect to have our ‘larnin kritisized’ in ‘ettemology’ and ‘swine-tax.’ We acknowledge the superiority of our neighbors, and although we have never represented ‘Kalamity’ County in the legislature, nor written poetry for the ‘Golden Era,’ we can readily understand and fully appreciate such beautiful and purely original sentiments as: ‘I’ve jest sot and sot till I’ve nearly rooted.”

Readers could laugh at Harte’s jab at the Times editor’s writing ability and also laugh at Wyman’s parry. But to catch the impact of Wyman’s thrust regarding the phrase having “never represented Kalamith County in the legislature,” they would have had to know that Colonel Whipple (and Wyman) dabbled in politics. (Whipple was appointed colonel by the legislature during the Klamath Indian Wars of 1852; he was later appointed Indian agent for Klamath and Humboldt Counties. Klamath County, by the way, was one of California’s original counties, but because of alleged dishonesty on the part of its government its size was chipped away by the formation of other counties, such as Humboldt, and was finally dissolved in 1874.)

In the December 10 issue Wyman also pecked at the Union newspaper and its acting editor: “LARGE RADDISH. Some friend has laid a very large and peculiar shaped raddish on our table. We intend sending it to the Northern Californian as a present to the junior editor.”

Harte fielded each attack with finesse on December 14, Regarding the radish he reprinted the Times article and wrote: “If the peculiar shape of the radish be owing to its being so very badly spelt, we would remark that we have already too many specimens from that editor’s table.”

Regarding “ettemology” and “swinetax” Harte wrote this little story:

The hogs about Union have petitioned for the repeal of the ‘Hog Ordinance.’ They give as a reason that they don’t know anything about a ‘swine-tax.’

And regarding poetry and politics:

We were once acquainted with an individual who never published any poetry, or represented any county. His singular condition may be attributed to the fact that the publishers rejected the former and the people didn’t nominate him to the latter.

Three days later Wyman responded:

The editor of the Northern Californian once knew an ‘individual’ who didn’t represent ‘any county’ because the people didn’t nominate him. We have the pleasure of an acquaintance with an individual who didn’t represent a county after the party did nominate him.

There the matter stayed, although in January Harte printed that on New Year’s Eve, “someone who ought to know better chose this time to get drunk and create a disturbance.” There is no way to prove the gentleman in question was really Wyman; if it were, the Times preferred to remain quiet—perhaps because Wyman’s fondness for imbibing was too well known. Eureka had its own term for “having one last drink,” called “Let’s wing round the circle.” It was said to be “the favorite expression of A. J. just before he is carried to bed,” according to the Times a few years later.

Events went along quietly for the next month until February 26, 1860. Whipple was in Eureka, again on his way to San Francisco, leaving Harte in charge of the paper. At four o’clock on a Sunday morning, Wiyot Indians, asleep on what was called Günther Island, were massacred. With them were friends and relatives from the lower reaches of the Mad and Eel Rivers. Only a very few escaped the knives, axes and hatchets of the reported five or six white men. Two gunshots were fired and heard in Eureka.

A number of Union residents were awakened by the anguished cries of the Mad River Indians as they passed by on their way home. From the impression made on Harte, it seems quite likely he saw a number of the victims himself, many of them dead, dying or disfigured for life. It was said that there were about 70 Indians on the island and only a very few escaped death or wounds in the massacre.

Harte elaborated on the slaughter under a 14-point headline:

INDISCRIMINATE MASSACRE OF INDIANS WOMEN AND CHILDREN BUTCHERED

…Little children and old women were mercilessly stabbed and their skulls crushed by axes. When the bodies were landed in Union, a more shocking and revolting spectacle never was exhibited to the eyes of a Christian and civilized people. Old women, wrinkled and decrepit, lay weltering in blood, their brains dashed out and dabbed with long grey hair. Infants, scarse a span long, with their faces cloven with hatchets and their bodies ghastly with wounds…

Whipple in his account forwarded from Eureka said it was a sickening and pitiful sight.

But Harte wasn’t through yet. In writing an editorial he gave the reasons leading to the massacre, but then to the indignation of the populace he more than condemned the atrocity:

The people of this county have been long suffering and patient. They have had homes plundered, property destroyed, and the lives of friends sacrificed. The protection of the Federal Force has been found inadequate…

But we can conceive of no palliation for woman and child slaughter. We can conceive of no wrong that a babe’s blood can atone for. Perhaps we do not rightly understand the doctrine of ‘extermination.’ How a human, with the faculty of memory, who could recall his mother’s grey hairs, who could remember how he had been taught to respect age and decrepitude, who had ever looked upon a helpless infant with a father’s eye could with cruel unpitying hand carry out the ‘extermination’ that his brain had conceived—who could smite the mother and child wontonly and cruelly — few men can understand. What amount of suffering it takes to make a man a babe-killer is a question for future moralists. What will justify it should be a question of present law.

Such an editorial written for a proextermination readership could only bring scorn upon Harte and the Northern Californian. The rival Times felt it had to defend the massacre:

There are men in this county, as there may be elsewhere, where the Government allows these degraded diggers to roam at large, and plunder and murder without restraint, who have become perfectly desperate, and we have here some of the fruits of that desperation. They have had friends or relatives cruelly and savagely butchered, their homes made desolate, and their hard-earned property destroyed by these sneaking, cowardly wretches; and when an attempt is made to hunt them from their hiding places in the mountains, to administer merited punishment upon them, they escape to friendly ranches on the coast for protection…

…If in defense of your property and your all, it becomes necessary to break up these hiding places of your mountain enemies, so be it; but for heavens sake, in doing this, do not forget to what race you belong.

We say this in all kindness, and sincerely hope that such an indiscriminate slaughter may never occur again in this county.

So much feeling was stirred up in the county that two months later, in April, a grand jury investigation was called. But as no one came forward to accuse the “perpetrators of this outrage,” there were no indictments.

In March of 1860 Harte was asked to leave Whipple’s employ. Major A.H. Murdock, Whipple’s partner, admitted that articles written by Harte had put Murdock in possible physical danger. Present day reports that Harte “sat at his desk with loaded revolvers” seems to be an exaggerated statement. Harte, it was said, “couldn’t hit the side of a barn,” and no one knew it better than he. Perhaps the idea was suggested from a much earlier remark Harte made in the paper with reference to a few things left with him which were waiting for Whipple’s return: “…a derringer, which won’t imitate his (Whipple’s) example and go off, a challenge, two quarrels, a letter written in an indignant female hand…”

Francis Bret Harte left the redwood country on the steamer Columbia on March 26. Whipple wrote a friendly send-off, published in the Northern California, saying he wished Mr. Harte great success and was sure his talent would be soon recognized. Editor Wyman even reprinted Whipple’s remarks. A few months later the Northern Californian merged with the Times.

Four years later, though, Wyman remarked on his erstwhile rival’s success: “Mr. F.B. Harte, formerly of this county, and a very pleasing writer, has taken charge of the Californian, a literary paper published in San Francisco.” Absence had made the heart grow fonder.

San Francisco, at this time in history, had become a mecca for aspiring writers; in fact, all facets of culture had a ready audience in the gold-plated city, already on fire with its own ambition. Harte, his style polished by his efforts on the Northern Californian, found ready employment and a measure of acceptance in the literary world that centered on Montgomery Street. With the publishing of “Luck of Roaring Camp” (1868), he was on his way to national fame.

###

The author appreciates the generosity of Martha Beers Roscoe for excerpts from her copy of the Northern Californian, the cooperation received from the reference librarians at Humboldt State University and the Humboldt County Library.

###

The story above was originally printed in the November-December 1987 issue of The Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society, and is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE