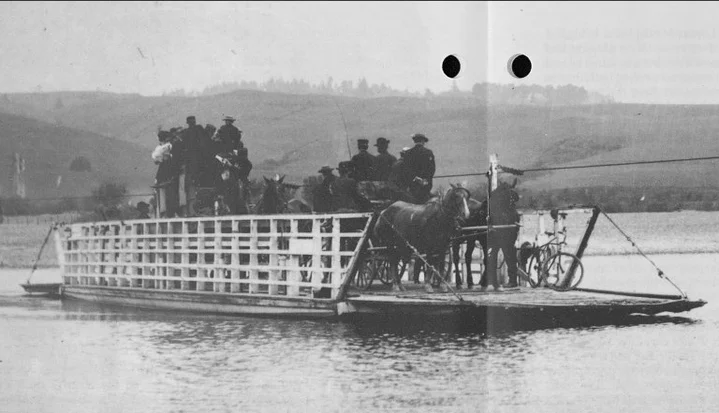

The Singley Ferry went through many changes in ownership throughout several decades, yet always remained essential to the residents of the lower Eel Valley. Photo courtesy of Ferndale Museum, scanned from the Historian.

Although the Eel River can be calm and picturesque — a place for picnics and swimming like all rivers — it can also be unpredictable and dangerous. This was especially true in the late 1800s and early 1900s when crossing the water entailed a great deal more than zooming across a bridge in a car.

Though the water was a lifeline to the Eel River communities which cropped up alongside it, it was also a barrier. Before Fernbridge was built in 1911, the only way to cross the Eel was either by going straight through the water in a wagon or on a horse, crossing one of the pontoon bridges which were put in during low water in the summer, or using the ferries.

All methods had an element of danger — fording most of all. In fact most drivers wouldn’t risk fording if they had another choice. When the water was low, however, and with a good team of trustworthy horses it could be done most of the time without trouble. Still, it could be a harrowing experience.

Katherine Casanova, who grew up in Ferndale, remembers fording the Eel as a young girl in a spring wagon. She sat behind her parents in the removable children’s seat of the wagon, watching the wheels rolling in the tracks made by others’ crossings. The sound changed and she heard the grating of wagon wheels in the wet gravel of the river. She watched the water climb higher and higher up the spokes. It had reached the middle of the wheel! Katherine screamed. Fortunately, because they were crossing in summer, nothing more frightening than this happened and they came out on the other side safe and sound.

Fording the river didn’t have to be frightening — sometimes it could be downright amusing instead. It was generally windy down at the river; you literally had to hang on to your hat. Once Dora Casanova’s sunbonnet blew off in the wind. She watched, unable to do a thing, as it flew through the air, landed in the river, and was swirled away by the current.

Always there was a possibility of danger though, and ferries were generally preferred as being safer and more convenient. There were three of these “flat wooden barge-like boats” in operation on the Eel. Singley’s, East’s, and Dungan’s ferries glided quietly across the river, controlled by cables attached to both banks or by the ferrymens’ poles.

“It is a fond memory,” Andrew Genzoli once wrote of the ferries, “brought back by the quiet creaking of a block or the muffled crunch of a pole along the gravel of the bottom.”

Singley Ferry was the most important of the three. It was established in 1861 when William Bradford, a 36-year-old native of Illinois, threw his cable out across the Eel at the foot of Table Bluff opposite George A. Singley’s house. Although in the 1860 census Bradford’s listed occupation was “groom,” he did well as a ferryman until he decided to retire from ferrying in the late 1860s and hand the business over.

The ferry went through many changes in ownership throughout the next several decades, always remaining essential to the residents of the lower Eel Valley. In 1884, when it was established as a railroad shipping station, it became even more important. Farmers came from miles around to ship their produce at “Singley’s Station” on the north side of the river.

Although it was such a popular crossing, not everyone used the ferry. In fact, until 1891 when a steam winch was installed, a pontoon bridge was used whenever low water made it possible.

The year 1891 was an eventful one for Singley Ferry. The Humboldt Times reported the destruction of the faithful ferry “Black Maria,” stating: “The ‘Black Maria’ is no more. [The ferrymen] are in mourning, for the staunch old dug-out has done great service…and in times of high water could always be relied on. …The current was never too strong for the ‘Black Maria’ to stem. … Apparently a pile of floating driftwood had hit the moored ferry at night ‘demolishing her beyond repair.’ “

Despite this small disaster, Singley’s continued to carry passengers and freight across the Eel. In 1910 it was still doing a phenomenal business. Viola McBride, who spent her childhood in Ferndale, remembers going to the Singley Ferry in 1910. Her four-year-old eyes were impressed with the size of it; in addition to her family’s car (an old model with big drum brass headlights) the ferry carried a four-horse stage, more than one horse and buggy, several saddle horses, and a couple of cows.

The crowded state of the ferry, along with the increasing number of automobiles, could be dangerous for people with horses. Drivers would often get out to soothe their team, holding the horses’ heads and talking to them softly to calm them down. And the ferry itself was not the only danger. Singley’s hill on the north side of the river was extremely steep. Horses were always bolting and acting up.

In 1877 the notorious hill caused what the Humboldt Times called an accident of “a somewhat serious nature.” Charley Stone had been heading up the hill in his buggy, driving a pair of “fine horses.” Suddenly, the horses spooked. They wheeled around, overturned the buggy and spilled the startled Stone onto the ground. He watched, helpless, as they flew down the bank, and “plunged into the river.”

Stone watched, but the horses had disappeared beneath the waters of the Eel. Nothing was seen of horses or buggy but a single cushion “that went floating down with the current.” It was assumed that the team had stumbled into a hole and gotten stuck.

In all instances, a good, calm horse a driver could trust was invaluable — especially when that driver had to cross the unpredictable river on the crowded ferry.

Singley’s, though quite popular, was not the only ferry along the Eel. The East brothers’ ferry, which was farther upriver than Singley’s and near Alton, was also commonly used. Generally it was frequented by people from Grizzly Bluff and Alton, but in certain circumstances other travelers used the East’s Ferry. The Eureka newspaper reported: “Several teams were compelled to drive through Fortuna last evening and cross at East’s Ferry in order to get to the Ferndale side. The ferry house at Singley’s is so far from the river on the Ferndale side that travelers on the other bank were unable to raise the ferryman.”

Fortunately for the “several teams,” the ferryman at East’s heard them ringing the bell and they were able to cross the river.

Although it was known as the “East’s Ferry” at this time, it had originally been established by a man named Barnett in 1880. Six years later, John East had purchased it; the community approved. In 1891 the Ferndale Enterprise stated: “Mr. East has [the ferry] in good shape, and will accommodate the public as well as the best of [strangers].”

Throughout the 27 or 28 years that the East brothers owned the ferry, the operation generally went smoothly, although there was at least one mishap. In 1896 the river rose, tore the ferry from its cable, and sent it swirling down to Centerville where it was found smashed beyond repair. A new ferry was built with lumber that the East brothers purchased from San Francisco. According to the Ferndale Enterprise, this was “the finest ferry ever operated.”

Between this “fine” ferry and the ferry at Singley’s, almost everything and everybody got across the water. However, there was another ferry, west of Singley’s, called Dungan’s Ferry. It was established in 1861 and ran, as the other ferries did, until the building of the bridge in 1911.

The idea of building a bridge across the Eel had been around officially since 1898. The Ferndale Enterprise wrote an article about a petition supporting the idea of a bridge. This petition had been “industriously circulated in the Eel River Valley.” The Enterprise predicted that the bridge would cost $60,000 — “perhaps more” — which could be easily raised in four or five years. They saw no problem getting the money. It was finding the site, they predicted, that would be difficult. They foresaw the bridge somewhere near the Singley Ferry section.

The people living in Grizzly Bluff near the East’s Ferry, however, had different ideas. In May of 1894, 25 Grizzly Bluff citizens met and declared that they wanted the bridge to be built at the East’s crossing. They elected a committee to “agitate the aroused interest” in this issue. Unfortunately for the Grizzly Bluffers, no one else in the county wanted the bridge at East’s, and the idea was soon dropped. The Ferndale Enterprise had made an accurate prediction. The bridge would indeed be built at Singley’s crossing.

Fernbridge’s completion was celebrated Nov. 17,1916. The bridge cost $245,967— an extravagant sum at that time.

Though this prediction had come true, their estimate of $60,000 did not; the bridge actually cost $245,967. Fortunately this sum, which seemed extravagant at the time, was provided by funds raised by taxation. Consequently the bridge was paid for by the time it was finished.

The high cost was due to the special new structure planned for the bridge-to-be. The engineering and design plans of John D. Leonard included a bridge of reinforced concrete. He’d already had experience with this material, as he had used it to construct several buildings in San Francisco. At first, the city didn’t like the buildings. Who’d ever heard of building something out of concrete? They also thought the structures were very ugly. However, after the buildings had withstood the San Francisco earthquake intact, the citizens began to look on them more tolerantly.

The residents of the Eel River Valley looked forward to their new bridge not with tolerance, but with pride. “The length of the individual spans of the new bridge surpass any other reinforced concrete bridge in the world in size…” bragged the Humboldt Standard. Everyone was impressed with the size of the magnificent future bridge. The Humboldt Times carefully pointed out the details: “The bridge had a length of approximately 2,500 feet, 1,025 being devoted to the approaches. …The roadway across the bridge is 24 feet wide, the cement bulwarks on each side being about one foot in thickness.”

A great deal of man-power and material went into constructing such a “queen of bridges.” Some 19,500 barrels of cement were poured and reinforced with miles of steel cable. Tons of gravel from the Eel River bed itself were also used.

All these raw supplies were molded into the form of a bridge by “men, donkey-engines, Sonoma graders, Fresno scrapers, wagons, and man-pushed and horse-drawn gear.” There was no heavy machinery available.

With so much going on, the construction of the bridge was a big event in itself, although it only took one year. People flocked to see the wooden skeleton slowly filling out and taking shape.

Evelyn Whitney’s father was one of those who knew a big event when he saw one. He brought Evelyn, who was only six, and her aunt, who was about three years older, to walk along the catwalk. This wooden “sidewalk” along the side of the bridge was for the workmen and was only one or two boards wide. Evelyn’s aunt was frightened and clung to Evelyn’s father. He had to help her across, but told his daughter, “Go ahead, Evelyn, I know you can do it.” With this, the six-year-old marched across the bridge unaided. When she got to the other side, there was nothing to do but march right back — and so she did.

But if a lot of people came to see the bridge in the making, everyone came to see the finished product. The paper reported that “as far as the Valley towns are concerned, a starving man will not be able to buy five cents worth of onions in Ferndale and Fortuna. Those towns will move bag and baggage to the new bridge.”

A “Celebration of Fernbridge” was planned for Thursday, Nov. 17, 1911. The courthouse in Eureka closed down, and the Board of Trustees declared a holiday. Schoolgirls released from classes were put to work slicing hundreds of loaves of bread. Tons of fresh beef sizzled in the barbecue pits. There were speakers in abundance, and even a brass band. Trains from Eureka to the bridge ran at a special $1 per-round-trip rate. People poured in on buses from Ferndale.

Not even the fact that it was raining fazed the celebrators. In fact it is said that, being Humboldters after all, “the rain was accepted as a part of the observances — a sort of christening.”

At the end of the celebration. Chairman Coonan called for three cheers. Someone from the crowd remembers that “the chorus of voices echoed through the wet air, bouncing from span to span and out into the hills.”

The building of the bridge inspired pride because of what it brought to the residents of the valley. People began to move around more and contact with “the outside” expanded. The variety of goods and the ease with which they were transported also increased.

But though the bridge aroused such gratitude and pride in most, in some it also inspired mischief. In its early days, the approaches were much steeper than they are today. One day Viola McBride was driving with a friend and her friend’s “fellow.” As Viola neared the steep approach to the bridge, she noticed, much to her irritation, that they were kissing in the back seat. She decided to put a quick stop to this. Coming up to the sharp bend between the steep approach and the flat part of the bridge, she slammed her foot on the gas pedal. The car flew up into the air and landed with a thump. The girl was very surprised — and quite annoyed — but Viola was satisfied.

Such stories about the bridge abound in the Eel River Valley. The bridge is truly a landmark for the community. Fernbridge is, as everyone is quick to point out, a “sturdy” bridge that has survived a great deal. It is not only a “monumental” structure, as the California Division of Highways notes, but is also unique and beautiful. It represents home to those who live near it. As Andrew Genzoli, historian and long-time resident of Ferndale, said, “For the person who has made his or her home in Ferndale or the Eel River Valley, the sudden appearance of the long graceful arches of the old bridge, be it from the east or the west, fills one with warmth.”

###

Original editor’s note: “Tamara Smith, author of this manuscript, received the first place award in this year’s Humboldt County Historical Society Scholarship Contest. Smith, a student at Fortuna Union High School, received her award of $250 during the May general meeting of the Society.”

###

The story above was originally printed in the July-August 1992 issue of The Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society, and is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE