Restoration workers stand above Iron Gate Dam on the Klamath River, roughly five miles south of the Oregon border. | Screenshot from the video “Restoring Balance,” which is embedded below.

###

In a monumental step that’s taken decades to achieve, work has officially begun on the world’s largest-ever dam-removal project.

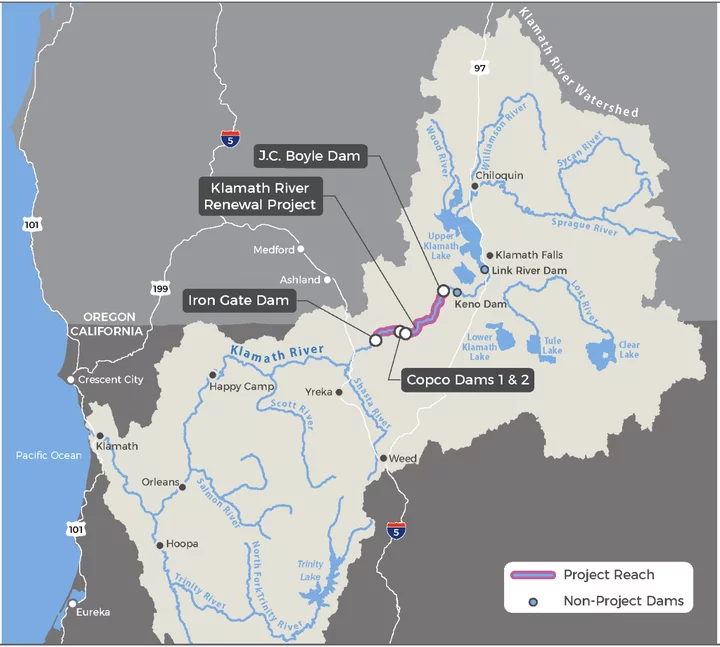

This complex endeavor will entail both removal of the four dams that comprise the Lower Klamath Hydropower Project, formerly owned by PacifiCorp, and major environmental restoration in and around the land that has been sitting at the bottom of man-made reservoirs for more than a century.

In a Zoom press conference this morning, Craig Tucker, a consultant working with the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, noted that this also represents the world’s largest salmon restoration project to date.

“And as most of you know, this can’t come a moment too soon,” he added, referencing the latest dire population forecasts for salmon in Northern California rivers.

The restoration component of the project will return about 38 miles of upstream habitat “to a free-flowing, more natural condition,” Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC) CEO Mark Bransom explained during the press conference. “And the restoration work is every bit as important as removing these dams.”

Following authorization from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), workers broke ground on March 10, building access roads and reinforcing bridges that will allow dam-removal contractor Kiewit Infrastructure West to bring in heavy construction equipment.

This enabling construction work is expected to continue through the rest of this year, preparing for drawdown of the reservoirs and then removal of the dams beginning in January of 2024, Bransom said.

The smallest of the four dams — Copco No. 2, which stands a mere 35 feet tall — will actually come down sooner than that, with demolition work starting in June and continuing through September or thereabouts.

Crews will employ low-level outlet works, which will be constructed this summer, to draw down the reservoirs and flush the water and accumulated sediment from behind the other three dams — J.C. Boyle (76 feet tall), Iron Gate (173 feet tall) and Copco No. 1 (225 feet tall).

Bransom said the water release will be very controlled, allowing workers to draw down the reservoirs slowly enough to ensure that there’s no over-bank flooding. With more than 100 years of accumulated sediment behind the dams, regulators and tribes have directed KRRC to undertake the drawdown work in the winter, when there’s the least biological activity and the highest probability of high-volume flows.

“We certainly acknowledge that this is going to have a significant impact on water-quality parameters,” Bransom said, though he said the estimated amount of accumulated material — five to seven million cubic yards of very fine sediment released over the course of three to four months — is roughly equivalent to what the Klamath River transports annually.

KRRC has committed to long-term monitoring and stands ready to address any issues that may result from deposition, Bransom added, noting that the monitoring will extend out to the ocean beyond the mouth of the Klamath.

After the drawdown of the reservoirs, workers will redirect the river around the construction site using diversion tunnels that were part of the original construction of the dams. This will allow the dam infrastructure to be removed from a dry river channel.

“So our schedule has us removing all four of the dams and restoring the Klamath River to a free-flowing condition … by the end of 2024,” Bransom said.

Project vicinity map via KRRC.

###

The restoration work is being managed by Texas-based firm RES (Resource Environmental Solutions), whose director of operations for the Northern California and Southern Oregon region, Dave Coffman, was on hand for today’s press conference.

“Dam removal can be a little bit of a messy business,” he said. “So we’re here to get reservoir sediment stabilized through reestablishment of native vegetation, provide some immediate, high-quality habitat for returning salmonids as they make their way through former dam footprints and into river channels where they haven’t been in over 100 years and really jumpstart the recovery of this landscape.”

Since 2019 RES has been working with partners in the Karuk and Yurok tribes, who’ve been onsite collecting seeds of native plants that will provide the foundation for sediment stabilization following dam removal.

“We’re somewhere in the ballpark of 17 billion seeds — native seeds — all either sourced directly from the Klamath Basin or sourced from plants that were grown from seeds that were sourced from the Klamath Basin,” Coffman said.

He recently moved a 2,000-pound pallet of seed into cold storage, in preparation for planting, and was impressed by the scale of it.

“And then I’m told, ‘Oh, this is just one of 50 pallets,’” he recalled, noting that there are literally tons and tons of seed coming onto the project site, seed that was provided by farms up and down the West Coast.

Restoration work will also be done on priority tributaries. Banks will be graded and habitat features of wood and rock will be installed to collect spawning gravels.

Tucker estimated that roughly 400 miles of fish habitat, including the main stem Klamath, creeks and tributaries, will be restored as a result of dam removal.

Wendy Ferris, KRRC board member appointed by the Karuk Tribe, said it can be difficult to fully articulate the sense of connection that tribes from the Klamath River Basin have with the land. Those tribes have existed for thousands of years, she said, and when European settlers arrived, they took the land away from the type of management that local tribes had passed down through oral teachings.

“And so, through time, [tribe members] were placed on reservations and their land was shrunk to very small land bases, which didn’t allow them to practice the religion fully … ,” Ferris said. “And when I say ‘practice the religion,’ what I mean by that is, the land is the Bible of the native people. So the rules of their religion lie within those ponds, creeks, rivers, animals and all living things around them.”

For local tribe members, restoring the river ecosystem represents “basically the first phase of bringing back our religion to a healthy state and being able to have healthy people and [to] live in balance,” Ferris said.

For more details on the restoration project you can check out the new 15-minute video “Restoring Balance,” which was produced by RES and is embedded at the bottom of this post.

You can also read the following press release from KRRC:

Yreka, CA – Work has officially begun on removing the four dams that comprise the Lower Klamath Hydropower Project. “Crews are already in the field doing the preliminary work for dam removal,” explained Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC) Chief Executive Officer Mark Bransom. “This work includes bridge upgrades, new road construction to access the dam sites more easily, worksite development, and more.”

The plan to remove the lower four Klamath River dams and restore the 38-mile river reach to a natural free flowing condition stems from an agreement between previous dam owner PacifiCorp, the states of California and Oregon, the Karuk Tribe, the Yurok Tribe, and a host of conservation and fishing organizations. The plan was formally approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission late last year.

“These dams provide no irrigation for agriculture, are not operated for flood control, and generate very little power,” explained KRRC Board president Brian Johnson. “But they do play a huge role in the decline of Pacific salmon. This project aims to fix that.”

The project is funded by $200 million from PacifiCorp and $250 million from a California Water Bond passed in 2014.

“We have several milestones associated with the project to highlight this year,” noted Bransom, “this includes the replacement of a drinking water line for the city of Yreka in May and the removal of Copco 2 Dam by September.”

The three larger dams are to be removed next year with removal of all four dams completed by the end of 2024; however, the restoration of the 38 mile reach of river impacted by the dams will take longer. That restoration process is already underway as well.

“We wanted to get a running start on this project,” explains Dave Coffman, the Northern California and Southern Oregon Director of Resource Environmental Solutions (RES). “Our crews spent several years collecting thousands of native seeds from plants around the reservoir sites that we propagated at commercial nurseries to become 17 billion seeds and thousands of saplings. As soon as the reservoirs are drawn down, we will immediately start the restoration process by seeding these areas.” This particular project is one of several highlighted in the film Restoring Balance.

RES will be reconnecting critical tributaries and ensuring fish can once again access over 400 miles of historical habitat upstream of the dams. Added Coffman, “we are excited to help bring this reach of the river back to life. RES will be here as long as it takes to make this project successful.”

Local tribes have led the effort to remove the dams for over 20 years and are particularly excited to see the project begin. “Dam removal is the first giant leap towards a restored Klamath River,” noted Wendy Ferris, KRRC Board member appointed by the Karuk Tribe. “We look forward to welcoming the salmon back home to areas they haven’t visited in more than a century.”

Similar sentiments were shared by Karuk Tribal Chairman Russell ‘Buster’ Attebery. “Many people told us this day would never come. Well, it’s here now and the salmon are coming home. I can tell you this is just the beginning - there’s a lot more restoration coming to the Klamath Basin.”

“We want to thank everyone who helped make this dream a reality,” noted Yurok Vice-Chairman Frankie Joe Myers. “It just goes to show what we can accomplish when the Tribes and our allies in the conservation movement join forces in common cause.”

###

CLICK TO MANAGE