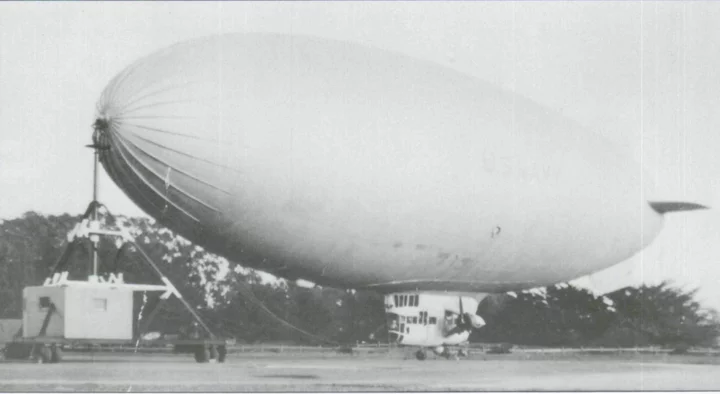

Pictured is the U.S. Navy blimp K-47 at rest at the Eureka base, c. 1943-45. Photos courtesy of the author, via the Humboldt Historian.

The sneak attack of the Japanese on U.S. Navy ships at Pearl Harbor set off defensive action along the Pacific Coast and Humboldt County was no exception. The U.S. Coast Guard set up regular patrols at every beach where a landing might be possible. Military men rode horses on the long beaches while, on the smaller beaches, trained dogs accompanied the men as they kept an eye out for enemy invaders.

Airplane watches were set up, which involved many women trained to watch for and recognize enemy planes. They reported to central headquarters any and every unknown flight passing overhead.

A Civil Defense system was set up, complete with headquarters, block captains and air raid wardens throughout various coastal communities. Bomb shelters were set up to supply food and first aid — just in case. Radiological monitors were trained to detect any radioactive material in case of a nuclear bomb attack (this writer went through this training).

At the very beginning of the war, Dec. 19, 1941, the general petroleum tanker Emidio was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine off the coast of Eureka. The entire United States was well aware that the Pacific Coast was in danger.

The shipping lines were warned of Japanese submarines possibly lurking in the coastal waters. The U.S. Navy set up submarine patrols with the command headquarters located at U.S. Naval Air Station Moffett Field in California. The station was commissioned Jan. 31,1942. The U.S. Navy set up the first blimp base at Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay during March 1942. The second auxiliary facility was established at Watsonville, Calif., and anti-submarine patrol operations began from that station. These bases were established all along the Pacific Coast.

In the beginning these non-rigid airships, or blimps, used for patrol were type “L” or primary trainer. These measured 150 feet long and featured a car 23 feet long. On Oct. 31, 1942, the first “K” type patrol airship was received by the squadron, a blimp designed for submarine patrol and convoy duty. It measured 251 and a half feet long, with a car 42 feet long. Several of these type “Ks” were stationed along the coast. Despite the different types, all of these blimps were non-rigid (no frame) structures featuring large gas bags filled with helium.

These blimps featured two Pratt-Whitney R-1340-AN2, 425-HP radial gasoline engines, one on each side of the car or gondola. They boasted a maximum air speed of 67.5 knots per hour (speed varied with wind conditions). They cruised about 50 knots per hour. The ships carried 1,500 gallons of aviation fuel, enough for 38+ hours of flight, with a range of 1,910 nautical miles. The blimps carried a crew of 10. Each blimp carried four, 500-pound depth charges.

When activated and dropped, these charges were set to explode at a certain depth in the ocean. The blimps also had one 50-caliber machine gun mounted over the gondola.

If a blimp left the base with a full load of fuel and, for reasons such as high winds or dense fog conditions had to return to the base, 1,000 gallons of fuel would be dumped into Humboldt Bay to lighten the load and lesson the danger of fire.

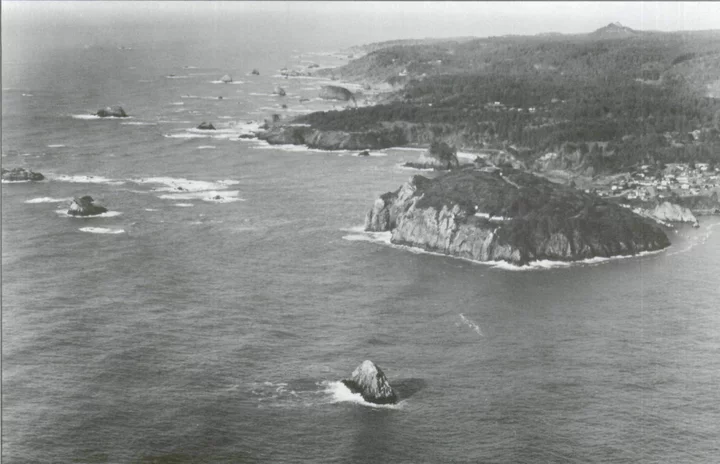

The Eureka Blimp Base at Humboldt Bay (note the two anchor spaces), c. 1942-45.

On May 22, 1943, the squadron began patrol operations from the auxiliary base at Eureka, with Lieutenant W.W. Bemis, U.S. Navy, serving as pilot aboard the K-47. This blimp base was located where the Eureka Samoa Airport is today, on the north Humboldt Bay peninsula.

These blimps would convoy ships as the crew watched for submarines. They also convoyed many of the big U.S. Navy dry docks built in Eureka by the Chicago Bridge & Iron Co. Some of these dry docks were towed to San Francisco, others to the Hawaiian Islands. While on these long flights, blimps would refuel on the aircraft carriers in the convoy.

Trinidad Head and its waters in the foreground is where a blimp reportedly sunk a Japanese submarine in 1945.

The war offered many exciting times for these blimp sailors. Several times the servicemen sighted periscopes of submarines at sea and, appropriately, dropped depth charges. They also assisted in rescue work of shipwrecks, helped lost fishermen and reported floating objects that were hazards to vessels. The Eureka blimp reportedly blasted at least one sub off the coast of Trinidad.

When these blimp sailors had short liberty, they would head for Vic’s Tavern in Samoa for a few beers and hamburgers, or for the Hotel Vance Log Cabin where they would play the jukebox. They enjoyed all the latest tunes of the day, i.e. the Andrew Sisters and “Little Lambs Eat Ivy,” “The Chattanooga Choo-Choo,” “I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire” and “The White Cliffs of Dover.”

Members of the Blimp Combat Crew #45 including (back row, left to right) R.F. “Matee” Mattson, S.L. “Battle” Beattie, J.A. “Mike” Michaels, J.B. “Dama” Earnest and V.R. “Virgie” Juide; (front row, left to right) Lt. J. “Bodie” Biedback, Lt. R.W. White and Ensign N.C. Hunt.

Blimp Base servicemen included at one time: (back row, left to right) J. Hodges, W. Williams, Ray Lay (fire chief of Eureka during the ‘60s and ‘70s), S. Hernandes and R. Dooley; (front row, left to right) unknown, Sy Beattie, unknown, unknown.

Combat Crew #34 members included: (back row, left to right) K.R. “Junior” Woolard, Vic Larcher and N.L. Hunt; (front row, left to right) J.A. “Mike” Michaels, J.B. Earnest, M.E. Szot, D.T. “Bud” Grenville and S.L. Beattie.

Some of these blimp sailors had girlfriends attending Eureka High School. One day, while they were returning from patrol, they buzzed the high school. While down at very low elevation, they flew over the building with their tie-down ropes dragging the roof, and revved up the engines. The principal of the high school called the commander at the base to report this incident. The crew was severely reprimanded for this action, which they did not do again.

The first Japanese attack on U.S. mainland in 1942 was triggered by cactus spines connecting with a Japanese naval captain. The story goes:

In the late 1930s, Kozo Nishino served as commander of a Japanese tanker taking on crude oil at the Ellwood Oil Field near Santa Barbara, Calif. On the way up the path from the beach to a formal ceremony welcoming him and his crew, Nishino slipped and fell into a prickly pear cactus. Workers on a nearby oil rig broke into guffaws at the sight of the proud commander having cactus spines plucked from his posterior. Then and there the humiliated Nishino swore to get even.

He had to wait for the war between the United States and Japan. But on Feb. 23,1942, he got his revenge. From 7:07 to 7:45 p.m., he directed the shelling of the Ellwood Oil Field from his submarine, the I-17. Though about 25 shells were fired from a 5 and a half-inch deck gun, little damage was done. One rig needed a $500 repair job after the shelling and one man was wounded while trying to defuse an unexploded shell.

U.S. planes gave chase, but Nishino got away. The blimp patrol was, of course, in on this chase.

Thereafter, American coastal defenses were improved; the mainland suffered only one more submarine attack by the Japanese during the war, at Fort Stevens in Oregon.

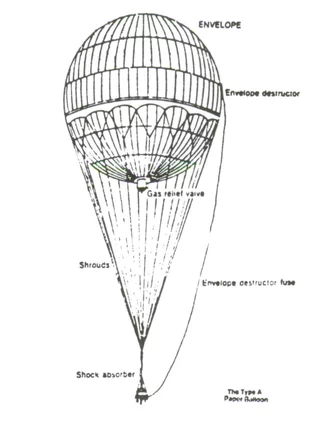

Probably the strangest bombing campaign in warfare history was launched by the Japanese. This bombing campaign was launched against the entire North American continent in the waning years of World War II; a feeble attempt by the Japanese to get back at the forces who were then laying waste to vast stretches of Japan. The Japanese resorted to the oldest form of aerial transport: balloons.

Thousands of hydrogen-filled paper balloons, most of them carrying one small high-explosive and several even smaller incendiary bombs, were launched from the Japanese home islands. The plan was that the eastward currents of the Jetstream would carry them to North America where, with luck, they would blow up something valuable or set a forest fire. About 9,300 of these lighter-than-air aircraft were released and about 300 are known to have stayed aloft all the way across the Pacific.

The first of the balloons to have approached this country was found floating in the Pacific, 66 miles off San Pedro Nov. 4, 1944.

The last landed in Wood Buffalo National Park in Alberta, Canada, about the time the Japanese surrendered in 1945. The first of these silent visitors to Northern California lit at Sebastopol Jan. 4, 1945. All told, 23 of these bomb- bearing balloons came down in California, all in the northern part of the state.

On January 10, an Army Air Force P38 shot down one of these wind-borne raiders near Alturas; it was taken to Moffett Field for examination. Part of another was found near Red Bluff and one was found caught in a treetop near Hayfork. Still bits of another were found near Cloverdale. In March, one draped itself over power lines in Butte County. On April 1, one came down on Hoopa Indian Reservation land.

Yet, for all their high hopes, the Japanese accomplished almost nothing with their balloons — with one tragic exception. On May 5, 1945, a church group on an outing at Bly, Ore., about 60 miles east of Klamath Falls, discovered one of these balloons in a forest. They began to tug at the balloon. It exploded, killing the minister’s wife, who was five months pregnant with what would have been her first child, and five members of the Sunday school class, ranging in age from 11 to 14. Today a memorial stands on the spot in that forest.

Another view of a blimp ready for action.

But back to the blimps and their operation: before taking off on a flight, the blimp would be filled with fuel, food supplies and drinking water. Then the total weight was checked to be sure they were not too heavy. Next boarded the flight crew of eight to 10 men, including the pilot (a U.S. Navy officer). The engines would be revved-up until they were running smooth. The pilot would then give the signal and the long hold down lines would be stowed on board, allowing the blimp to take off. The flight might be north to Tillamook, Ore., or south to San Francisco. The crew had to watch the weather conditions and fuel supply as to not go past “the point of no return.” An electric generator supplied 110 volts of electricity for cooking in the small galley as well as other needs. In general, the crew was quite comfortable on board.

Radar equipment on board could detect a submarine periscope at three or even four miles distance. Also, M. A.D. (Magnetic Action Detection) could detect any metal object on the ocean’s surface or at quite a depth at sea.

Upon their return to the Eureka base, the crew would dump any surplus gas and drop down to the landing area where the 30- to 40-man landing crew would be waiting for them (they had been in touch by radio). When the blimp was finally secured, the tie-down tower would be towed out by a small tractor and a man would climb up the tower and anchor the blimp. A gas winch on the tower would pull the blimp in tight and … all was well. The crew was ready for a good night’s rest. In case a high wind came up, the crew had to be there to take care of the blimp.

These are the men whom I am aware of who stayed here after the war: Sy Beattie, Frank Toner, I.A. Davis, Ray Lay (later fire chief of Eureka), and Charles Steele of Crescent City. These men comprised the flight crews. In addition, there were ground crew men such as Joseph Carter of Eureka.

On Monday, July 14, 1947, Joe Russ Jr., a Capetown rancher, noticed a U.S. Navy blimp cruising southward off Cape Mendocino after completing a photographic mission off Point St. George. The blimp was moving along at an elevation of about 400 feet when all of a sudden it hit a terrific down draft. The airship plunged nose-first into the sea. The command pilot, Lt. Duane DeVaney, put the ship to full throttle in an attempt to divert the crash, but she struck at 50 knots. The front section of the gondola was smashed. Pilot Lt. DeVaney and Lt. Britton Goetze, co-pilot, were thrown clear while six others took to the water. Three men leaped out of the gondola as the blimp drifted unmanned into the air, from a height of some 50 feet. It was first reported there were two men still aboard — not so.

Ray Crockett, Cape Mendocino lighthouse keeper, also witnessed the disaster. He logged the crash at 2:50 p.m. Joe Russ called the U.S. Coast Guard station, which then radioed the Blunts Reef’s lightship. The Coast Guard sent out a rubber raft and picked up the men. A lifeboat from Humboldt Bay station arrived, eventually bringing the 11 men to Eureka for the night. All were reported safe.

The Coast Guard called Al Camilli at the Humboldt County Airport to ask if airport personnel could track the blimp. A plane flown by Paul Fleming, with Pete Sacchi as observer, tracked the blimp to the location where it crashed; on Fickle Hill near the Minor Rock Quarry at 5:30 p.m. Les Brown and Duane Geddon raced to the scene in an ambulance. Brown, first at the scene, said it was being looted by souvenir hunters who had broken a trail through the heavy brush and were taking instruments, food rations and clothing.

A U.S. Coast Guard armed guard was soon posted. The Navy thought of saving the blimp but the skin was badly torn and all of the helium gas had escaped; those plans were abandoned. The Navy did retrieve most of the papers and instruments, including the machine gun and ammo. This particular blimp had been used on submarine patrol along the Pacific Coast during World War II. An official U.S. Navy report of the accident is as follows:

This ZPK-99 was assigned from Moffett Field. It carried three civilians on a sea lion photographic flight, July 13, 1947, at the request of the California Division of Fish and Game. The ZPK-99 was inadvertently flown into the water, washing the pilot out through a smashed window. The crew abandoned ship and were rescued in about 30 minutes. The airship “free ballooned” some three hours and came to rest some 16 miles north of Arcata, Calif.

The 11 men listed as being on board the ill fated blimp were; Lt. Duane DeVaney, pilot, San Jose, Calif; Lt. Britton Goetze, co-pilot, Minneapolis, Minn.; Lt. John Butler, Lincoln, N.D.; Schuyler Borum, Idaho; J. Losita, seaman first class; Milton Alley, aviation mechanic first class; Wallace Kundra, radio 2/c second class; and Tom Theotopatos, photographer second class.

These 11 men took part in just one of the many adventures surrounding the blimps and their relatively brief stay on the North Coast.

###

The story above was originally printed in the Autumn 1994 issue of The Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society, and is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE