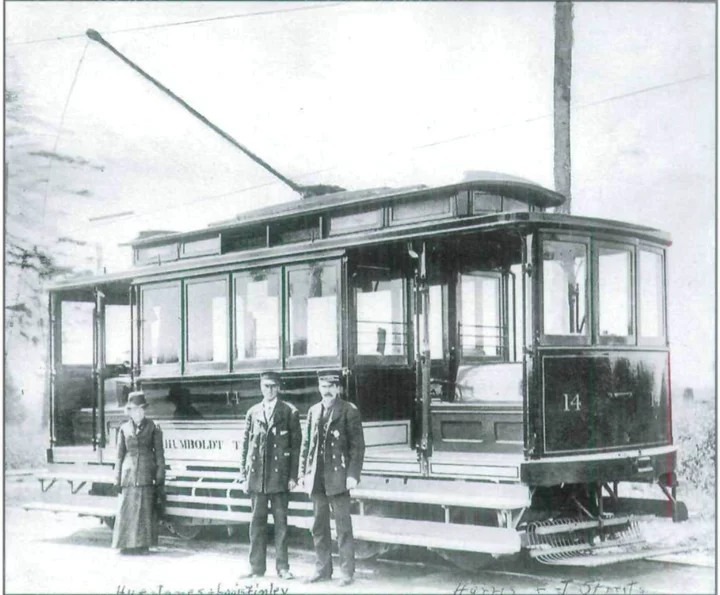

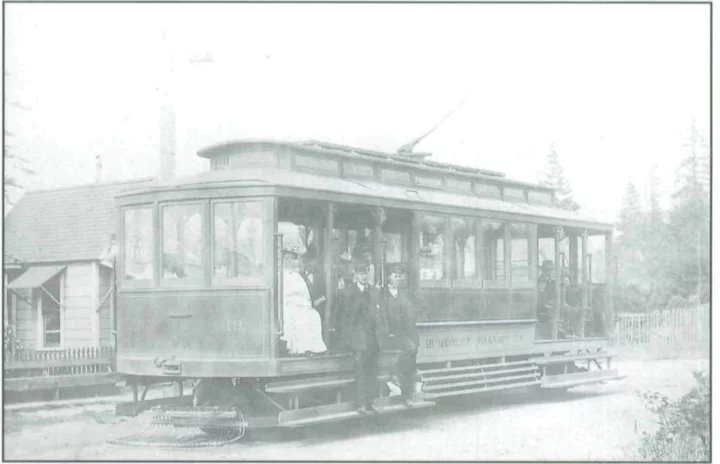

A Eureka trolley at Harris and J Streets, with an unidentified passenger and conductors Hue Jones and Louis Finley. Photos: Humboldt Historian.

“Clang, clang, clang,” went the Eureka trolley. “Ding, ding, ding,” sounded the streetcar’s warning bell. The streetcar was either about to cross an intersection or continue its journey if it had stopped for passengers. Some students might have ridden the streetcar to school in the 1920s and 30s. It passed right by Marshall Elementary School, and Eureka Junior and Senior High Schools on J Street. But my sisters and I walked to school from our home on Harris Street. During the Great Depression, my family did not have money to spend on trolley fares. While we were in elementary school, we allowed half an hour to walk to school, but as we grew older, and walked faster, we needed only fifteen or twenty minutes to get to the Junior High or Senior High School.

One afternoon in 1932 I heard the “clang, clang” of the streetcar bell as I walked home from first grade at Marshall School. The trolley made its way down J Street, traveling at what appeared to be three or four miles per hour. Gray clouds filled the sky. It looked like rain. It felt like rain. It even smelled like rain, you know — the smell of wet dust in the air? I smiled and skipped along. If it rained, I could try out my brand-new raincoat. It was favorite shade of green. Green like Granny Smith apples in the fall. As Street — my street, where some sidewalks were the old wooden style with deep rain gutters made from straight, vertical grained redwood boards — the gray clouds grew darker. I unsnapped the gripper on my new, transparent, apple-green carrying bag, took out my raincoat, and put it on. Then I folded the carrying bag and slipped it into a pocket. I held the cellophane raincoat close around me while I looked up at the dark clouds.

I hoped it would rain.

J Street, not paved like Harris Street in front of my house, but graveled and oiled, stretched behind me with the streetcar tracks going right down the center like metallic ribbons all the way north to downtown Eureka. Shiny tracks also stretched south to Harris Street. On the other side of Harris, J Street became a one-lane dirt road. The streetcar tracks turned the corner onto Harris where they joined the Harris Street line. Streetcar barns stood on the northeast corner of Harris and J Streets. At night, streetcars were stored there and also at another car barn downtown, on Second and A Streets, next to the Eureka Electric Car Lines Depot.

###

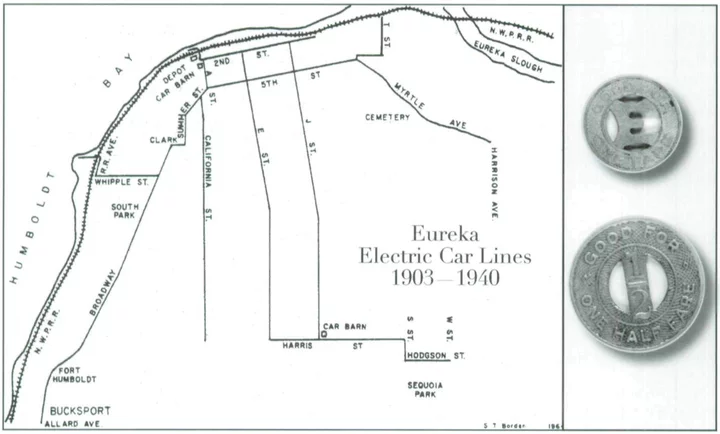

Streetcar system map, with tokens.

Streetcars were an important mode of transportation in Eureka during the Depression. I remember the fare being three cents, or two tokens for five cents, but this must have been the fare for children. Sarah Haman of the Humboldt County Historical Society researched this and found out tht the one-way far for adults was originally five cents, then raised to six cents in 1918. By 1919, the adult fare had risen to ten cents. But in the depths of the Depression in 1933, it dropped back to five cents.

There were five main streetcar lines: Broadway to Bucksport; California Street to Harris Street; E Street to Sequoia Park via Harris Street; J Street to Sequoia Park via Harris Street; and Myrtle Avenue ending at Harrison Avenue. This arrangement of tracks served most of the town. All the lines had sections with double tracks at the halfway point, or more often if necessary, so that streetcars could pass each other. If a car going one direction reached the double tracks first, it waited on the siding until the car coming the other way had passed by.

One day when my little sister, Betty, was a baby, the street car conductor knocked on our door while holding Betty in his arms. When our mother answered the door, the conductor asked, “Is this your baby?”

Mother nodded.

“Well,” said the conductor, handing Betty to her, “She was sitting right in the middle of the street car tracks. It’s a good thing I saw her and stopped in time.”

Mother was mortified to think she had not watched her child more closely. My older sister, Pat, said the three of us had been outdoors playing in front of the house that day. Somehow, Pat and 1 had not noticed when the baby crawled out into the middle of the street and sat down. I must have been two years old and Pat six, when this happened.

It may have been after this incident that my mother asked me to watch out for Betty, or maybe I simply appointed myself my little sister’s guardian. One day my mother let us play with her “button jar”—a mayonnaise jar full of buttons that had fallen off shirts and dresses; or been cut from worn-out garments to save and re-use on new, home-sewn clothing. Other useful items such as snaps, hooks and eyes, and safety pins were also stored in this thrifty jar. Some of the safety pins were not fastened, but were open. I saw my baby sister put something shiny into her mouth. She would not let me take it out, but swallowed. The shiny thing disappeared. I was so afraid it was an open safety pin. I ran to tell my mother, and she hurried across the street with Betty to the General Hospital where an X-ray was taken. No open safety pin showed up, but a bright silvery metal snap with no sharp edges appeared, and passed right through her system.

###

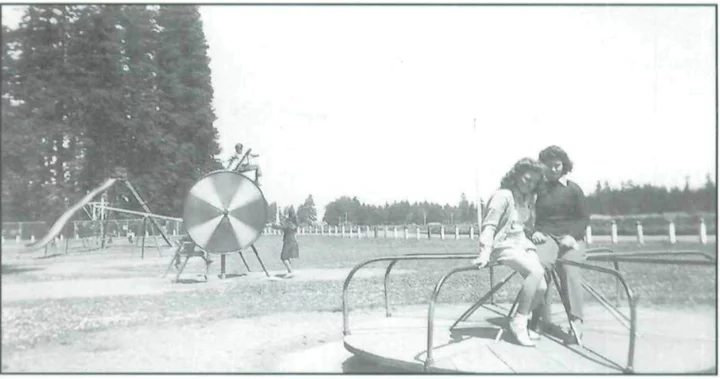

Sequoia Park, circa 1942. Betty Olsen and Nancy Lax (Gomez) sit on the notorious merry-go-round.

In the early 1930s, my father’s widowed sister, Carrie Sands, lived with her parents at Elk River. She would sometimes walk to the Broadway line at Bucksport and ride as far as our house. I had always thought she rode the Harris Street line from Broadway directly to our house at 816 Harris Street, but since the Harris line did not go any farther west than E Street, she must have ridden the Broadway car to Fifth Street downtown, and then taken the E Street car to Harris, a roundabout way to get there. Carrie picked up my little sister Betty and me, to take us to Sequoia Park.

We would stand in front of our house and flag down the next streetcar. Seats on each end of the car faced out and were not enclosed, although they were under the roof of the car. Other seats were inside. The conductor and the motorman wore three-piece black uniforms: coats, vests, and trousers with billed black hats that gave them a rather official look. Change holders on straps that fit over their vests and under their black coats were made with metal tubes fastened together, one for each coin denomination. These coin changers rested at their waists where they could easily make change, and a slot at the top of each coin tube made it easy to deposit the coins people paid. When we had boarded the streetcar, the motorman would step twice on a button embedded in the floor to activate the warning bell: the streetcar was about to move. “Clang! Clang!” went the trolley.

Eureka Electric Car Lines cars, built in 1903, took us all the way to the store at Sequoia Park where we bought peanuts to feed the monkeys in the Sequoia Park Zoo. We would spend part of the afternoon at the zoo where, in addition to the monkeys, a few bears existed, their lives sad and confined. An assortment of exotic birds like parrots and peacocks filled the air with chatter and bright colors. During the Depression, the city was hard-pressed to feed the animals and pay someone to care for them. As people in those days said, “Money was scarce as hen’s teeth.”

We always spent part of our afternoon at the playground, where swings hung on long chains from timbers fastened between tall redwood trees. Carrie pushed us, and when she “ran under” the swings, we felt like we were flying nearly to the sky. A large double slide, like a giant tripod, stood on the street side of the playground. One third of the tripod was a straight slide, another third, a slide with wavy bumps, and the last third, the ladder to reach the top. This tall slide was scary, but we went up the ladder, counting what was rumored to be one hundred steps. Carrie always stood at the bottom of the slide to catch us as we swooshed down.

Equipment for small children stood at the southeast corner of the playground, including a merry-go-round pushed by hand to make it turn. A deep groove had been worn around the merry-go-round from many feet running, while people pushed the contraption round and round. One day as we rode the merry-go-round, it got to moving pretty fast. My little sister, Betty, fell off and rolled underneath. There was enough room for Betty to scrunch down in the groove made by the many footsteps, and press her face into the soft dirt as she waited for us to get the merry-go-round to stop. Betty was a brave little girl. She did not cry. Much to everyone’s relief, she was not hurt.

A Victorian gazebo, trimmed with gingerbread and painted white, looked like a giant wedding cake in the center of the playground. Band concerts had been held here in the first two decades of the twentieth century, but were discontinued during the hard times of the Depression.

Beyond the playground was a stand of old second-growth redwood trees, which is still there. Tall redwood stumps left over from logging operations sometime in the late 1800s show evidence of the virgin timber that once grew there. If we had time, Carrie would take us down a trail in this primeval forest, through the hush of the tall trees with shafts of sunlight shining through their branches. Buttercups, salal, and sword ferns edged the trail that led to a pond at the bottom of the ravine where we fed the ducks and geese. If we looked carefully in the forest, we might find trilliums poking their white, three-petal blossoms out through the undergrowth like three-pointed woodsy stars. We followed the road as it went up the ravine and back to the store, where we waited for the next streetcar to take us home.

Streetcar #19 with passengers and conductors, near Sequoia Park, and is that Johnson’s store in the background?

###

There was no way to turn the streetcars around for the return trip, but the cars had controls at both ends, so they did not need to be turned around. However, the power had to be reversed to make the car go the other way. The conductor or motorman got off to reverse the metal pulley that touched an electric wire overhead and propelled the streetcar. He unfastened a rope and pulled down on it to release the pulleys contact with the overhead wire. He walked it around, pivoting the top of the pulley rod on the roof of the streetcar to the other end of the car, where he eased it back up to touch the wire. The wire must have been “live” to conduct electricity to the streetcar’s electric motor.

Once in a while, Carrie would take my sister Pat, who was four years older than me, with her on the streetcar to Sequoia Park to meet friends from Kneeland, laqua, and Showers Pass for potluck luncheons. Plans might have been made with penny postcards that were used prolifically in those days to communicate. Perhaps they telephoned. A party line went up the mountain to many of the ranches, each with its own special ring. If the telephone rang at one ranch, the caller could hear phones being picked up all along the line, each open phone making hearing a little more difficult, as the mountain folks listened to the gossip and news. People on isolated ranches became starved for some contact with others and looked forward to everyone else’s telephone conversations.

Carrie always brought a kettle of beans to the park picnics—a staple on most tables during the 1930s. Other people brought other things, maybe crisp, fresh vegetables from a kitchen garden, perhaps homemade bread and fresh churned butter made from the cream their dairy cows delivered; or layer cake topped with fresh strawberries and whipped cream.

###

On summer days, we children put small rocks on the J Street tracks before the streetcar ratcheted by. We stood back, safe on the sidewalk, to watch the spurts of dust made when the wheels crushed the pebbles. Once in a while, a child put a penny on the track and let the streetcar flatten it, but Betty and I usually held our pennies tight in our hands, if we were lucky enough to have them, and ran down Harris Street to the corner grocery store on “K” Street for penny candy.

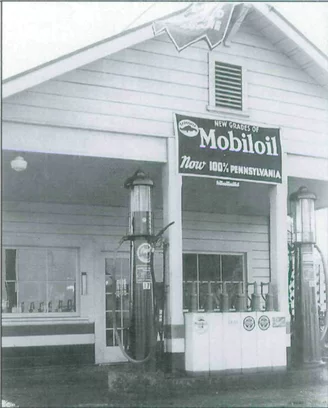

The shop and gas station of the author’s father, Mike Olsen. This photo was taken before the fire that started when someone tossed a lit cigarette into a bucket of gasoline used to clean car parts. Right away, the Olsen family and friends got to work rebuilding it.

Pennies were rare. Once in a great while we went to our dad’s repair shop next door to our house, and asked him for a penny. He showed us how to open the office till and let us each take one penny. Four brass keys like the keys on a piano hid under a metal shield on the left hand side of the oak till. We pressed the secret combination of the top and bottom keys with our pointer and pinky fingers, pushed a brass button on the corner of the till with our thumb, and the cash drawer opened with a little bell-like noise: “Ka-ching!” Our father trusted us with this knowledge and we did not betray his trust. We told no one else how to open the cash drawer. Not until this very moment. One penny each was all we took, and we never took pennies without his permission.

We ran almost as fast as the streetcar traveled the short distance to Christiansen’s corner grocery store, where we could buy ten wrapped candies for a penny, or one purple grape-flavored sucker shaped like a lion’s head, or a strip of paper with little candy dots all in a row. Red, green, white, yellow. For five cents, Mr. Christiansen cut off a rectangle of Ghirardelli’s milk chocolate from a large block of chocolate an inch thick, scored in rectangles of two inches by three inches. This was my favorite treat. I nibbled on my piece of chocolate if I had one, like a little mouse and tried to make it last as long as possible, but I rarely had a nickel to buy chocolate. If we dropped our pennies on the way to the store, they might disappear between the cracks of the wooden sidewalks that edged Harris Street in front of the cow pasture next to our house. A wooden sidewalk also ran along the empty block between J and K Streets, across the street from the streetcar barns. Then we needed to find some chewing gum to put on a stick and try to get the penny back.

My older sister, Pat, and her best friend, Francis Naas, who lived across the street from us, used to ride the streetcar downtown to the Carnegie Library on Seventh and F Streets. They must have been at least twelve years old, as the fare for them was five cents each way—the adult fare. They would bring home four books apiece, the maximum number the library allowed, and spread them out on Fran’s front porch in the sun, where they spent many peaceful hours reading. The girls had a rule that they could not peek in the back of the book to find out what happened, but must read the book all the way through.

Cement sidewalks edged the corner of Harris and J in front of the car barns, making a wonderful place to roller skate. Betty and I put on our roller skates and fastened them with a skate key that tightened the skate clamps onto the soles of our shoes. Leather straps buckled around our ankles. We skated half a block along J Street on one side of the streetcar barns, turned the corner and skated another half block in the other direction along Harris Street. Sections where the streetcar tracks entered and exited the barns were difficult to maneuver, but the smooth sidewalks were ideal for skating.

###

Frank Frost, conductor of car 13, at Myrtle and Harrison Avenues.

And now back to the day of my new apple green raincoat. Before I reached my street on my way home from Marshall School that gray day, black clouds spilled their contents over Eureka. The sky turned into a leaky sieve above my head. Huge drops splattered down. Wind nearly knocked me over. I was elated. This was the perfect chance to test my new raincoat. In no time at all, the deep redwood rain gutters edging the wooden sidewalks ran full to overflowing. 1 held my new raincoat together, tucked my head under the cellophane hood, and walked faster.

Across from the car barns, on the northwest corner of Harris and J Streets, stood a vacant lot where alder trees and willows grew among ferns and salal bushes. Wild blackberry vines sent out their runners onto the wooden sidewalk. As I reached the end of this block, a gust of wind caught my cellophane raincoat and ripped it up the back. The hood fell from my head. Cold water trickled down my neck. I shivered. My shredded raincoat hung from my shoulders. Buckets of rain fell from the sky. I could see my house across Harris Street, cold and wet with rain weeping from its eaves. The wet holly trees on either side of the front porch steps glistened like patent leather. My father’s service station and shop on the other side of the house appeared hazy through the downpour.

Sheets of water covered the intersection of Harris and J Streets and splashed with each step I took as I crossed the street. I ran the half block to my house and sloshed up the stairs to the front porch where I stood under the roof overhang, dripping rain from the tatters of my once beautiful raincoat. It had definitely not passed its first and only test. The familiar “Clang! Clang!” of the streetcar filled the air. I turned to watch it go by. Passengers rode inside out of the rain, warm and dry, not wet and soggy like me.

The street car wended its way along Harris Street, past my father’s shop and past the General Hospital between H and I Streets. It rocked back and forth as it trundled along toward E Street and the big wooden water tanks on the corner. Its metal wheels complained on the metal rails, and polished them smooth. The Eureka Electric Car Line streetcar disappeared in the rain.

###

The story above was originally printed in the Summer 2009 issue of The Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society, and is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE