Epicurus (341–270 BC), the Greek founder of Epicureanism, has often been given a bad rap through the ages, having been unfairly portrayed as a glutton, drunkard and womanizer by those who feared his hedonistic philosophy. He was indeed a hedonist — pleasure and absence of pain and fear are worthy goals in life, he said.* In particular, we shouldn’t fear a hellish afterlife — a common belief both in his time and place and in America today. (Pew reports 58% of Americans believe in hell.) He taught that there is no afterlife, just as there is no life before we are born: “We are not before birth, then we are, then we are not.” The soul (he believed in souls) dies with the body. For Epicurus, no “…dread of something after death/The undiscovered country from whose bourn/No traveler returns.” (Hamlet)

* I wonder what he thought of delayed gratification. We endure pain to achieve something pleasurable in the future: Six years of struggling through college, working two jobs to pay the bills, to end up with a Masters, for example.

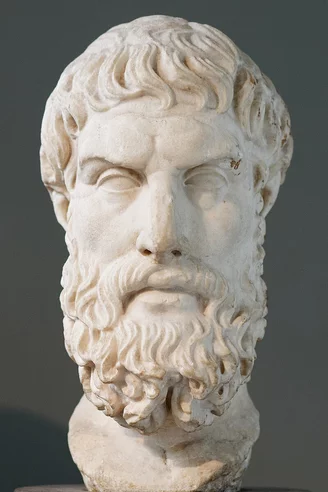

Marble portrait of Epicurus, Roman copy after a lost Hellenistic original, now in the British Museum (Marie-Lan Nguyen, public domain)

Epicurus’ morality was simple: we act ethically, not out of fear of punishment—either by fellow humans in this life or by the gods the next—but because amoral behavior inevitably leads to guilt and remorse. (“There’s no peace for the wicked.”) For many centuries—perhaps still—this approach was condemned by the Catholic Church, which taught that the only way to keep people on the straight and narrow was to stoke their fear of eternal punishment in hell.

So what does acting “ethically” look like in the real world? Epicurus’ disciple Philodemus put it this way (in a book preserved in the pumice of Herculaneum, buried in AD 79 by volcanic ash from Mount Vesuvius): “It is impossible to live pleasurably without living prudently and honorably and justly, and also without living courageously and temperately and magnanimously, and without making friends and being philanthropic.”

Speaking of friends, Epicurus’ “Garden” in Athens, where he taught, was unusual for encouraging women and slaves to join.

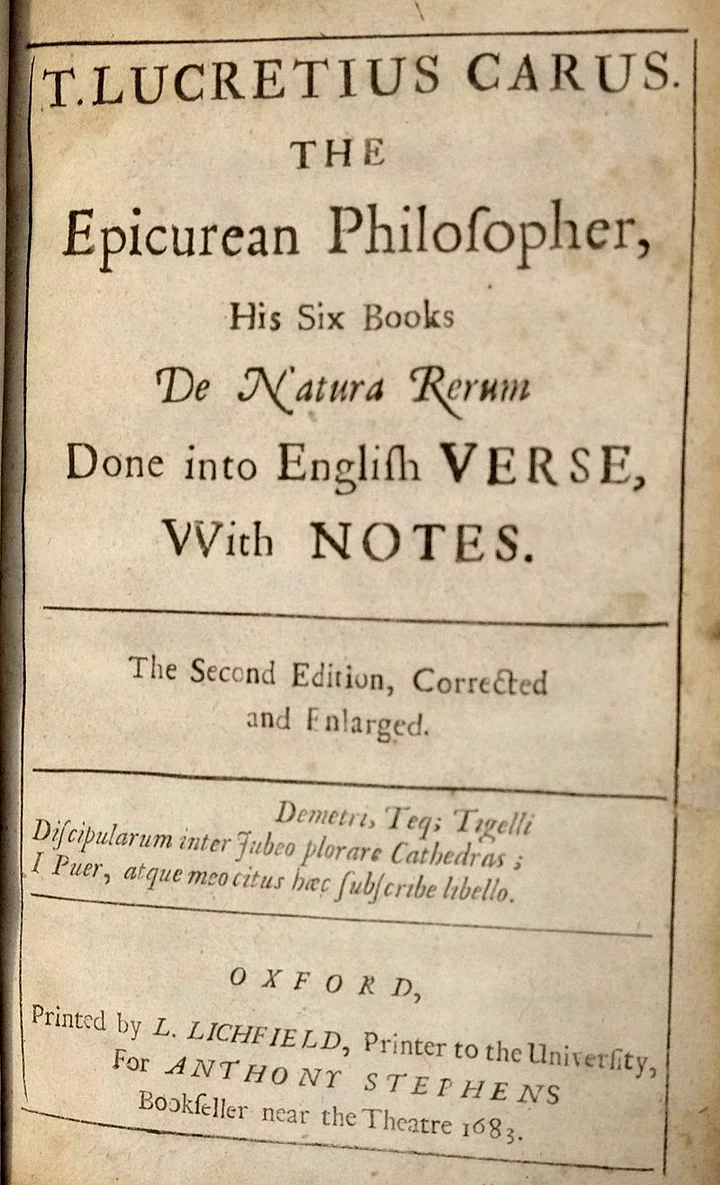

Curiously, he wasn’t an atheist. Like virtually everyone in his time, Epicurus believed in gods. But he thought they had better things to do than worry about mere humans, “…as if divine beings depended for their happiness on our mumbled words or good behavior.” (I’m quoting Stephen Greenblatt. His book The Swerve is the story of how a copy of De Natura Rerum, a poetic re-telling of the philosophy of Epicurus by his greatest fan, the Roman poet Lucretius, surfaced in a remote monastery 600 years ago.)

Title page of a 1683 English translation of De Natura Rerum (Public domain)

After a millennium of condemnation and/or obscurity, Epicurean thought returned during the Enlightenment, when its appeal to pleasure over pain, happiness over fear, and kindness over cruelty, resonated with freethinkers. Galileo, Montaigne, Shakespeare, Molière, Voltaire, Hume, Diderot—all found a kindred soul in Epicurus. And Thomas Jefferson. When asked by a correspondent about his philosophy, Jefferson replied, “I am an Epicurean.”

CLICK TO MANAGE