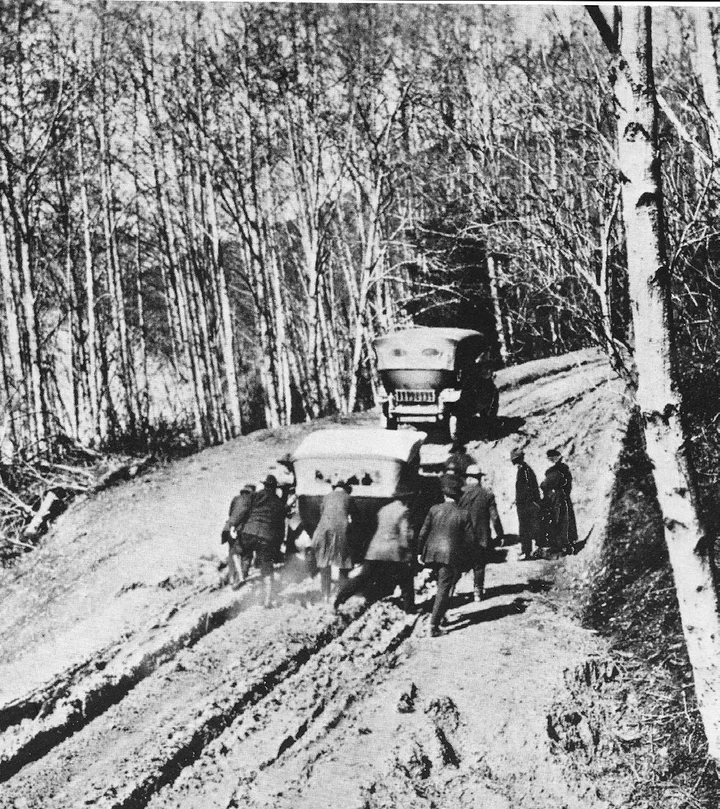

White steam cars arrive in Eureka for the new Overland Auto Stage Co., c. 1907. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

I have always loved antique cars, have always collected early auto memorabilia, and have always been interested in the history of the automobile and of transportation in Humboldt County.

I recently discovered, however, that I had missed an important element of this history: the Overland Stage Company and the Overland Auto Stage Company.

It was a Eureka photo, seen above, in the July-August 2009 Horseless Carriage Gazette that brought the Overland Stage to my attention — and something else as well. The 1907-1908 caption for the photo reads:

Five White steam cars just put into service by the Overland Auto Company for stage travel between Eureka and Sherwood, California, a distance of 140 miles [actually about 110 miles]. White steam cars were selected after severe competitive tests.

This picture greatly piqued my interest. I have lived in Eureka nearly all my life. I know where Elinor is, but where is Sherwood?

Seeking information at the Humboldt County Historical Society, a staff member, Sarah Haman, overheard my question, “Where is Sherwood?” and said, “I used to live in Sherwood.” She went on to explain that Sherwood is about ten miles north of Willits:

When entering Willits from the north, at the first traffic signal, turn right. Proceed up the hill, soon coming into Sherwood Valley, drive about ten miles north, and there is Sherwood. It used to be an important mill and lumber town on the end of a NWP rail spur. Due to a fire in the valley some years ago, all that is left of Sherwood are foundations, one house, and the cemetery next to the school.

I guess I’ve never been to Sherwood, at least in my memory. My quest for information about the Overland Auto Stage Company, carrying travelers to Sherwood to catch the NWPRR to San Francisco, had begun. Although new to me, I’ve discovered many have written about the Overland Auto Stage Company, some from first hand experiences and knowledge. For me this has been a very new and exciting subject!

A horse-drawn stage south of Dyerville, circa 1908. Photo: Humboldt County Historical Society.

TRAVELING BY HORSEDRAWN STAGE AND RAILROAD SPURS TO SAN FRANCISCO

Humboldt’s first railroads were built by logging companies. As timber was logged farther from Humboldt Bay, railroads were constructed to the logging sites. These rails were also used for mail delivery and public travel between Humboldt Bay and Trinidad, Arcata, Blue Lake, Korbel, Eureka, Fortuna, Carlotta, Scotia, and Elinor, the end of the rail line south.

Elinor, also known as Camp #5 of Pacific Lumber Company, comprised an area covering both sides of the Eel River one mile north of Pepperwood. The Pacific Lumber Company built this rail line five miles south of Scotia. Elinor had a hotel called Camp Five Hotel built in 1905, along with two houses. Across the road were the railroad station and two more houses. A ferry service run by Jerry Meeker crossed the Eel River to Elinor Flat, near Dyerville, connecting railway passengers, who wanted to continue south, with the Overland Stage Company. Stages took passengers south to Sherwood, where they could board the NWPRR to Sausalito. Here they could catch the ferry across the bay to San Francisco (the Golden Gate Bridge was not built until the 1930s). The 110 miles (approximately) between Elinor and Sherwood was traveled by stages drawn by four horses, as seen in western movies. These coaches were said to be “the worst rig to travel in!”

I can imagine some aspects of the journey. During the mid-1930s, I traveled by auto to San Francisco with my folks, which was at that time still a two-day trip, staying overnight at the Hotel Willits during the summer months. No auto or hotel air conditioning and boy! Was it hot! Stopping along the way at the iced lemonade and orange juice stands, which were built in the shape of a lemon or an orange, was a cool treat.

I remember sitting under a big shade tree munching the ice. Roads were “almost highways,” certainly not as today, and they would have been even less so in 1908.

Passengers in the early days could also travel by steamship to and from San Francisco and Humboldt Bay aboard the Corona, the F.A. Kilburn, the Pomona and others. However, due to rough seas causing severe seasickness, not to mention the dangers (the Corona ran hard aground on the north spit of Humboldt Bay on March 1, 1907) many preferred the trip by stage. It had its dangers, too; it was a longer trip, and the roads were rough, but some travelers found comfort in having solid ground beneath them.

The original Overland Stage Company first began in the early 1880s and followed the 1884 mail route — Rohnerville, Bridgeville, Blocksburg, Alderpoint, Harris, and Bell Springs were towns on the old mail route road out of Humboldt County.

From around 1895, construction on the shorter Ridge Route (Harris Road, present-day Dyerville Loop Road) was underway, through Dyerville, McCann, Harris and Bell Springs. This was a shorter route — neither road surely no freeway — but it was rough, narrow, steep, twisting, dusty in dry weather and muddy in wet, and even dangerous with many steep drop-offs.

Smythe’s fleet for the Overland Auto Company, 1910. Photo: Humboldt County Historical Society.

NOW COMES THE AUTOMOBILE

Locally, one hundred years ago the transportation change from horses to autos was big news! Not quite the same as going to the moon. (Almost.)

That such a change could happen was simply inconceivable to most people, who felt about the same way as my late wife’s grandfather. As a young man, her father, Edward Davis, took care of the horses every day before and after school for his father, Henry Davis, who had a drayage company in Eureka. One day young Ed said to his father, “Pa, we’ve got to get a truck. McGarrigan’s [drayage] has a truck.” To which his father replied, “Hell, son, nothing will ever replace the horse.” Davis soon went out of business.

It was in 1906 that local newspapers first announced that a local company planned to use automobiles between Elinor and Sherwood, connecting the end of rail lines north and south between Eureka and San Francisco. The company then abandoned the scheme due to road laws of Mendocino County at the time.

These problems were solved over the next two years and on March 20, 1908, articles of incorporation were prepared by the law firm of Gregor and Connick. The new company retained the Overland name, but instead of the Overland Stage, it was now the Overland Auto Company. As published in the Standard, the company was set up as follows:

Mr. Fred W. Smythe [garage manager and the new enterprise’s prime owner] 400 shares $4000; N. H. Pine [of Eureka Foundry] 200 shares $2000; Clarence Long [molding mills] 300 shares $3000; William Kirk of Harris [one of the proprietors of the old company] 250 shares $2500; Henry G. Noe [livery man of old company] 150 shares $1500; H. A. Poland [shingle mfg.] 200 shares $2000.

In mid-April of 1908, officers of the company were named:

- N. H. Pine, President

- Clarence Long, Vice President

- William Dodge, Secretary

- H. W. Leach, Treasurer

- H. D. Melone of Englevale [near Dyerville],

General Superintendent

- F. Smythe

- H. G. Noe

It was decided that the new auto company would operate at least six months of the year, depending upon the weather, and the fare would be $20, lodging and meals included. During the winter months when rains would make the roads impassable for the new automobiles, they would have to operate the old horse-drawn stages, fare $12. Thus, one of the first things the new company had to complete was the purchase of the old company from Mr. H. P. Cross and William Kirk. The former company ran the distance of 105 miles from Camp #5 to Sherwood. The purchase consisted of about twenty stages, sixty horses, pastureland, barns, and harness equipment.

The Overland Auto Company set up new supply stations at Elinor, Pepperwood, Dyerville, Fruitland, Bell Springs, Cummings, and Sherwood. They also leased a hotel and forty acres of land at Sherwood, on which they built a garage and a large barn for accommodation of livestock and horse feed, and storage of oil, tires, tools, and automobile parts.

The company was awarded a government contract to carry the mail in the amount of $12,348 per year.

The first auto stage left Eureka for Sherwood at 8:45 a.m. on April 25, 1908. As reported in the Humboldt Standard, the auto stage carried:

N. H. Pine, president of the company, F. W. Smythe, three passengers: W. J. Jensen of Kansas City, C. W. McKinnnie of Oakland, and E. C. Mowry of Eureka, picking up Supervisor Williams at Fortuna.

Mr. Pine telephoned from Pepperwood to Eureka, that they had traveled 35 miles in about three hours and that the road was in fair condition.

Three days later, the Standard reports: “Mr. Pine sent a message to Eureka from San Francisco announcing that the Overland Auto trip was an entire success and that seven passengers were taken through without mishap or delay.”

By summertime the new auto stage was enjoying steady patronage. The Standard of July 17, 1908 reports:

Auto Stage Route is Very Popular – The popular mode of travel these days is in an auto and the trip is from San Francisco to Eureka. Arriving yesterday afternoon was Manager C. A. Eastman of the White Steamer Autos; Oscar T. Barber, an attorney of San Francisco; and Claude A. McGee, a photographer of the City who is securing views of the County for an eastern magazine. The party made the trip without mishap. When Laytonville was reached, F. W. Smythe of the Auto Stage Co. was secured to pilot the car through, he being more familiar with the roads.

A July 21, 1908 advertisement in the Standard reads:

The Overland Auto Company is operating auto and horse stages daily between the R. R. points –Thomas Fliers [sic] and White Steamers used exclusively. A comfortable daylight ride. Through fare Eureka to San Francisco auto $20, through fare stage [horse] $12. Good hotel accommodations along the route – office 521 2nd Street, phone main 131.

THE OVERLAND COMPANY AUTOS

There were unforeseen troubles from the beginning, because the original machines were not designed to withstand the steep grades and rough roads. As local historian and writer Evelyn McCormick writes in Living with Giants:

When auto stages came into general use here in 1908, the vehicles were seven-passenger White Steamers and a Thomas Flyer. These cars could not take the rough roads. So Mr. Smythe decided to revamp a five-passenger Maxwell adding an extra lower gear to make the steep hills. Bob Morrison, master mechanic, had a full-time job working with these autos. He strengthened the frame, changed the wheel size for 30” x 4” tires, and added the lower gears and readied the Maxwells for service.

The Humboldt Standard of July 30, 1909 announces:

Through Autos Will Run Sunday — The trip over the mountain by auto is an ideal one. The Maxwell machines are specifically adapted for the trip and the drivers on the route are gentlemen who know their business.

In 1910 Overland Auto Stage was operating out of 227 4th Street (NW corner 4th & D). Many may remember this as the Pacific Garage. The 1909-1910 Polk Directory lists the officers of the Overland Auto Co.: Clarence A. Long, President; Henry L. Ford, Vice President; Henry W. Leach, Secretary-Treasurer.

Mr. Smythe continued to add new models to his fleet, seeking the latest automotive advances. In 1910 he bought two Studebaker Garfords. These were 7-passenger, 4- cylinder, 4-speed transmission autos. “Although underpowered handled pretty well,” notes the Standard. He also ordered a new ten-passenger Pierce-Arrow. “The big machine is to be specially constructed for the run,” reports the Standard of August 13, 1910:

When in commission, it will run from Sherwood to Burke, the smaller cars handling the business from Burke to Holmes Camp [Burke being 5 miles northeast of Santa Rosa].

Business continued to boom. The following month the Standard reports:

That the Overland Auto line between this city and San Francisco is extremely popular may be judged from the fact that every trip the autos are filled to the utmost capacity. On some occasions it has been necessary to send two machines out instead of one and it is often the case that more passengers turn up at Holmes Camp than the capacity of the machines will allow to accommodate the increasing traffic. (September 1, 1910)

In the Standard of February 1, 1911, we read:

Overland Trip to be Much Shortened — Mr. Smythe says that he will start with five automobiles [next spring] and will add to them as needs arise. The coming spring and summer will no doubt be very busy ones on the Overland Road for the change in the train.

As railroad building continued, the trip to San Francisco grew easier: the Standard goes on to proudly announce that the entire trip from Eureka to San Francisco will soon take only twenty-three hours!

Schedules on shortening the gap by the new railroad building will make the overland trip a very easy and delightful one. From present indications the autos will run from Dyerville to Little Lake Valley [22 miles north of Ukiah]. It is announced that a train will leave this city early each morning early enough to get the passengers to Dyerville by 10:00 o’clock in the morning. The autos will then take the passengers in charge and land them at the end of the railroad in Mendocino County at about 6 p.m. A train with Pullman Sleeper attached will leave that point for San Francisco at 9 p.m. and will land the passengers from this city at their destination in the metropolis at about 6 o’clock the next morning, 23 hours after leaving Eureka. The train leaving San Francisco with Overland passengers for Eureka will depart from that city at 11 o’clock at night and connect with the early morning autos north and these passengers will be landed at Eureka early that evening.

When auto service took over from the horse stages in the Spring of 1911, the company was using six machines: two 48 hp seven-passenger Alcos, two seven-passenger Studebakers, the Maxwell, and a 66 hp Great Pierce Arrow.

The Great Pierce Arrow was a new addition to Smythe’s fleet. The Pierce had become the choice of auto to be used.

DRIVERS

Like the captains of steamships, the automobile drivers were entrusted with great responsibility as they ferried passengers through dust or rain over often harrowing roads. In a 1987 Humboldt Historian, George Kimball writes that while many preferred traveling overland, there being “no back door to a steamer,” that on the rocky narrow overland roads, along winding cliffs, the back door of an auto stage often opened onto a deadly precipice. “There were scores and scores of places along the road where an accident could not have been avoided,” writes Kimball of his 1908 trip, “if our driver had gone six inches, or sometimes only three inches, out of the regular beaten track.” Skilled drivers were vital to the Overland enterprise, and the drivers’ names were often included in newspaper announcements of upcoming trips, as in this Standard notice of May 2, 1911:

Leaving from the Pacific Garage, the machine, one of the new seven passenger ALCO’s, Tommy Silence in charge. It will go by way of Bridgeville and expects to reach Sherwood by noon tomorrow. Another machine will leave here tomorrow morning in charge of Ed Nellist, and another Thursday morning with Frank Nellist at the wheel, that is, they will leave if it is not raining too hard.

In March of 1911, Frank Nellist was arrested for speeding while driving voters to the polls for a bonding election. The Standard reports that Frank

intends to fight the case and his friends have retained ex-Judge A. W. Way to defend him. Judge Way while on the police bench was a terror to auto speedsters and set the fine limit at $50, but he now is on the other side and declared that the client will not be fined even the $15 maximum set by Judge Moore.” (March 3, 1911)

In 1912 the Overland Company began installing phone lines along the route. “Phone Line Is Being Built in Order to Avoid Delays Through Accidents to the Autos,” announces the Standard on August 8, 1912:

A telephone line from Twin Rocks to Harris is now being built by F. W. Smythe, Manager of the Overland Auto Company, while a similar line from Camp Grant to the top of Fruitland Hill is already in operation. These lines will be used in case of breakdowns or other delays in order that reserve machines may be brought out on the shortest possible notice and will greatly improve the conditions of overland travel.

This photo of passengers helping to push an auto stage through the mud on a hill near Trinidad gives us a good idea of road conditions in early 20th century Humboldt. Photo: Humboldt County Historical Society.

ROADS, WEATHER, MUD

Each year auto service began and ended according to weather and road conditions. Snow conditions began as early as October or November and lasted through the winter months, with heavy rains continuing through May and even late June. The auto stages ran only when road conditions permitted, usually from about May or June through October or November. Horse drawn stages operated when the autos could not. Newspapers announced the return of the auto stages each spring, and their end of service each fall.

Roads were narrow, graded, graveled in places, with steep hills and winding turns. When road conditions were bad, passengers were asked to disembark and walk around dangerous turns, such as the infamous Devil’s Elbow near McCann. When roads were muddy, machines bogged down and passengers had to help push them out of the mire.

Overland would send employees and drivers out in one of their cars to go over the road to get rid of high rocks, which could seriously damage an auto’s oil pan and lower portion of the engine. Workers used powder, caps, picks and shovels. They would put two or three sticks around any large rocks, cover them with mud and blow them up.

Each spring as soon as roads and weather permitted, the auto fleet was brought out for service. The April 16, 1913 Standard announces:

Gets Ready for Overland Auto Traffic — Manager Fred Smythe of the Overland Auto Service announces that he hopes to have his service to San Francisco in operation in about two weeks with accommodations for handling passengers daily. During the time the cars have been off the run this winter they have been overhauled, while additional station and garage facilities have been arranged, making large improvements in the possibilities of the equipment for handling increased traffic. Mr. Smythe expects that this year will witness the heaviest overland travel to date.

Weather is unpredictable and miscalculations were

bound to happen. Such was the case on this occasion.

Manager Smythe did put the Overland auto stages

back on the road at the beginning of May, but this

turned out to be too early. As the Standard reports:

Late Rain Put County Roads in Bad Condition and Overland Autos Out Of Service, While Auto Trucks are Encountering Trouble — Roads Likewise Bad in Other Counties … The commencement of heavy traffic over the roads of this county followed by the rains of the last several days has resulted in the county’s roads getting into about as bad condition as they have been this time of year for about a score of seasons. The service of the Overland Autos to Longvale has been discontinued. (May 23, 1913)

The auto trucks referred to above were hauling construction supplies on portions of the road close to the advancing rail line.

Two weeks later, in June, rains were still causing problems:

Slippery roads made it impossible for the Overland Auto Stages from San Francisco to leave on their scheduled trips this morning. While no permanent damage to the roads was done by the rains, Manager Smythe believed it was best to omit this trip from his schedule rather than take chances. The roads throughout the county are in good shape but with them hard, as they are at present, it takes but little rain to make them become slippery. (June 6, 1913)

Devil’s Elbow is a sharp, one-way hairpin turn on the Ridge Route from Bell Springs to McCann. Near McCann, the road is built into a rock cliff looking straight down onto the railroad tracks and the Eel River, as seen above. Photo: Humboldt County Historical Society.

FOOD AND LODGING

Travel over the 105 miles between Sherwood and Elinor occurred only during daylight hours, taking two days. Overnight lodging was provided at Sherwood, Bell Springs, and Cummings.

Driver Frank F. Nellist recalled that he and his fellow drivers enjoyed the food at most of the meal stops, which they took with the passengers:

We especially remember how Mrs. Wheat and Mrs. Bessmen at Dyerville always had fried chicken, biscuits and all the trimmings, it was really good. Part of the time our lunch stop was at Murphy’s place at Fruitland — that was a real place to eat, the food was the very best, but there were lots of yellowjackets also looking for lunch and although they never bothered much they made most of the passengers nervous. (Melendy Papers, 1961)

ACCIDENTS

Accidents were not uncommon, especially in bad weather. Both the horse-drawn stages and the automobile stages suffered upsets. The first serious accident for the Overland Auto Co. occurred on June 3, 1909, at 2:00 in the morning. The Standard reports:

About four miles up the hill from Cummings and a mile and a half from Blue Rock, the stage got near the outer edge of the road and the road being soft caused the horses and stage to slide over the grade and rolled down about twenty feet, landing with wheels up in the air. Everyone more or less bruised and no one seriously hurt. The driver held on to the reins and the team, after getting on their feet again, were headed up the hill, keeping a strain on the coach and prevented it from rolling over again. Clarence Long, manager of the Stage Company said the most severely injured was a passenger by the name of Moss, who was riding on the outside. His hip was badly bruised.

With him on the outside was Mrs. C. D. Howard, wife of local representative of Hills Brothers Spice Company. She was struck on the head by the stage cover when the vehicle went over. Her hat and heavy coiffure prevented an injury.

Other passengers were Mr. Murphy and Mr. Schaefer, who were late arriving in Eureka for their I.O.O.F. meeting. The horses were not injured.

It is not uncommon to read about accidents involving an auto and a horse and buggy during the early twentieth century when autos first began sharing the roads with horse-drawn conveyances. The Standard of September 12, 1910 reports that,

An Overland Stage Company auto collided with a buggy on Fruitland Hill, overturning the lighter horse-drawn vehicle, and breaking its axles. The occupants of the buggy, Mrs. Murphy of the Fruitland House [stage stop] and her grown daughter and two small children, were thrown out of the buggy, but not injured beyond a few bruises.

As the railroad advanced north from San Francisco, the stage road was used for hauling materials for the construction, and accidents were frequent due to the mud mires of the road, at times requiring the aid of several horses to pull the wagons out. On one occasion, reported in the January 2, 1911 Humboldt Standard, “a freight team with a load of hay ran into a mud hole near Dyerville and capsized. It took several hours of work to place the vehicle on the firm ground and replace the hay in proper place.”

END OF THE LINE FOR THE OVERLAND AUTO STAGE COMPANY

As the construction of the railroad progressed northerly, the auto stage line became shorter and shorter. Within a couple of weeks after the railroad was completed on October 23, 1914, the Overland Auto Company went out of business.

The final ad for the auto stage line appeared in the Standard on November 5, 1914:

Overland to San Francisco by Rail and Smythe Auto Service Commencing [next spring] May 03 leaving Eureka 3:45 p.m., arriving at San Francisco 7:35 p.m. Leaving San Francisco 7:45 a.m. arriving at Eureka at 9:50 a.m. Overnight stop both ways at Ft. Seward. No night traveling. Fare $20. For further information and tickets apply to any Northwestern Pacific Agent Advt.

The auto stages were sold. Passengers to and from San Francisco could travel straight through by North Western Pacific Railroad trains.

The road system continued to improve and still continues to do so today. Indeed, a reversal of the above eventually took place, and now we have good highways and fine automobiles, but no railroad.

The author with his models of a stage coach as used by the Overland Stage Co., and an early automobile

###

The story above was originally printed in the Winter 2013 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE