The cannon today. Photo: Instagram user @levisims40.

I grew up on the East Coast near former Revolutionary and Civil War battlefields, so old cannons

were everywhere and not much of a novelty. In their

original setting, bristling from a fort or looming over

a strategic inlet, they convey an image of strength, but

mostly they’re just obsolete iron tubes.

When I first saw the cannon in Arcata, in front of the Veteran’s Hall at 14th and J Streets, I was impressed with its graceful, long, lean lines, and also by the fact that some of the gadgetry for it to aim and fire remained. I wondered where it came from, and why is it here? Asking around, I heard two things from various people: that it was a captured World War II Japanese cannon, and that it had once been hauled up to Humboldt State University by mischievous students. I was curious to know more, and I was also concerned about the deterioration of its wooden spokes and wheel rims due to Humboldt’s wet climate.

I had an old house to restore, another to build, and more projects soon followed, but the gun stayed in the back of my mind. Not that I have any special affinity for cannons, but that particular one seemed worth saving. The steel would never rust away, but if its wheels rotted, much of its historic fabric would disappear. It wasn’t until recently that I had time to think about Humboldt’s largest gun again.

The author presents an artillery shell casing from a cannon of a similar size to the Arcata cannon. Photo: Bob Felter, via the Humboldt Historian

A new visit to the cannon revealed more rot in the wheels than I remembered, and I was determined to soak the wood with preservative. It wasn’t mine, however, and I wanted to get permission from whoever was in charge. In finding this person, I also hoped to learn the gun’s history. I mentioned this to native Humboldter Winnie Trump at a breakfast and she pointed to Al Toste, saying, “There’s the man to talk with.” Al said he’d bring the rot issue up at an American Legion meeting, and that the one person who’d know the history was Marino Sichi. “You should see him soon though — he’s in Timber Ridge Senior Center and his days are numbered.”

That was on a Friday. Sunday afternoon I went to Timber Ridge and asked to see Marino. I explained my presence, and despite some reluctance, the receptionist led me back to the nurse’s station. As tears came to her eyes, the nurse stammered, “Marino passed away this morning.” I think everyone who knew him loved him.

I persisted in my quest and made a call to Alan Baker, the Commander of the VFW/American Legion Hall, and he connected me with Ben Curtis, an active member of the Legion. I explained my concern about the rot and during our conversation it emerged that children loved to climb on the cannon, and that a real tragedy could occur if it were to collapse. Ben brought the issue up at the next American Legion meeting and it was decided they needed to do something. As he said, “We can’t let it go under our watch.”

The Legionnaires jacked the cannon up and placed a welded support underneath; I then got the okay to paint on preservative. Laws have affected what is available in California, and what’s in the stores now has only 9% copper naphthenate, is water based, and colored green. This contrasts with what was on the shelf two years ago, which was solvent based, came in green, brown or clear, and contained three times the amount of the same active ingredient. I didn’t want to use a green color on historic wheels, nor one that would leach out in our winter rains. Coincidentally, while on a job at this time, I came across an old, almost full gallon can of clear “good stuff ” and made a trade with its owner.

Now it was time to learn about the cannon. Linda DeLong, a researcher at the Humboldt County Historical Society, said that she also had once looked into it but found nothing. A stop at Arcata’s library also came up dry, and HSU’s Humboldt Room was closed for the holidays. I next thought about the old Arcata Union: they must have printed at least a mention when the cannon arrived in town. An email to local historian Susie Van Kirk, who is said to know “everything” historical about Arcata, revealed that she’d been through every issue of the Union since 1940, and had never seen anything.

Ben Curtis mentioned another possible source of information, a man named Virgil Freeman, who had left the area. So I made another call to Alan Baker, who provided the phone number of Virgil, who now lives in Fremont. Virgil had been in the VFW Post for decades and was a past Commander of the VFW/ American Legion Hall. Born in 1920, he spent forty months in the Pacific theater during World War II as a code clerk, sending and deciphering communications. He joined the lodge about 1955, when the cannon was already there, but knew some of its history. It’s likely he represented my last chance to learn about the cannon by word of mouth.

Virgil explained that before the war, a small cannon had sat on the Veteran’s Hall lawn. As hostilities overseas grew, the government called for scrap metal and the cannon was sent to the smelter. Much of America’s history met a similar fate. Perhaps the government remembered, or was reminded, of Arcata’s contribution, because after the war, said Virgil, they sent Arcata a replacement. But in an era when P-51 Mustangs and B-17 bombers were being left behind or pushed off the decks of ships as they crossed the ocean, why would an old iron relic such as this have come to the States? Virgil replied that the ships returning home after the war needed ballast. Anything heavy they could find was set down in the holds to keep the ships upright, and that a cannon would do a fine job of that. Arcata’s new cannon arrived in the port of Richmond, and came north on the Northwestern Pacific Railroad at a cost of $17. Virgil thought the bill of lading was somewhere in the VFW Hall. The gun was offloaded in Arcata at the old California Barrel Factory, and towed up to the Hall. Originally, a flagpole was there, and the gun sat to the north of the sidewalk, but it was later moved to the south side to allow for a wheelchair ramp. They set bolts in the slab for tie-downs, but never used them.

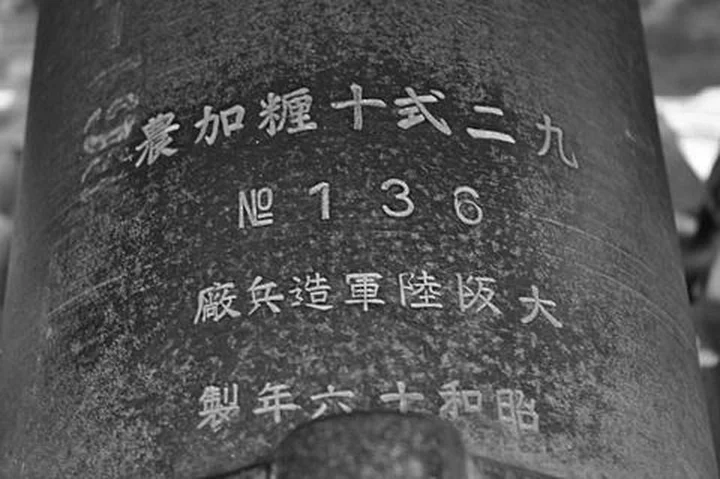

A close view of the inscription on Arcata’s cannon. Photo: Winnie Trump, via the Humboldt Historian.

A significant clue about the cannon was right on the barrel: four lines of mostly Asian writing above the breech. I wondered whom I could find to translate, then remembered a distant cousin who has a son in Japan. Lee said indeed, his son Matt speaks fluent Japanese, and supplied his email address. I shot off a couple photos of the inscriptions to Matt with a plea for help and a day later I learned more than I ever expected. The top line says it’s a Model 92, 10 cm (4”) cannon. The third line, below the No 136, says it was made by the Osaka Infantry Armory, and the bottom line tells us it was built in 1941. He went on the Internet and found a link to the armory where the gun was built and another link to the gun itself. All is in Japanese, which I can’t read, but the page showed a picture of an identical gun. Matt deciphered, “The series was first built in 1923 but was redesigned several times until its birth as a Model 92 in 1935. It was valued for its portability, but considered a bit lacking in power.”

Left: The cannon pays a surprise visit to Humboldt State, 1955. This photo is from the 1955 college yearbook, Sempervirens. The caption states that the identities of the students who dragged the cannon up to the campus and chained it to the stair railing at Founder’s Hall “is still a mystery, but it has been said that members of the Knights (whose Grand Duke, Howie Kraus, is shown facing camera) knew more than they would reveal.”

I had to laugh about “valued for its portability,” thinking back to the rumor of its once having been moved up to the HSU campus. The stories I’d heard were that Jim Ely never admitted to being part of that prank, but that he had returned it. While that sounds suspicious, Jim was the sort of guy who might have brought such a thing back regardless, so who’s to accuse? I considered Jim a friend, but he passed away before I thought to ask about it. A call to his sister, Mary Ann, however, led to a phone number for one of his best friends, Norm Eaton, who now lives in North Carolina.

Norm said that he had never admitted to taking the cannon either. A bit of prodding eventually led to a story. Other than Jim, Norm couldn’t recall who else was involved, nor who had the idea, but one night in 1956 at around 3:00 in the morning, about four guys hitched the cannon up behind Norm’s ’46 Plymouth.

“I didn’t have a trailer hitch or anything,” said Norm, I think we just tied it to the bumper or somewhere with some rope. We had to drive up the old way to Founder’s Hall, and somehow we got it up on the sidewalk below the front doors with it aimed out over the town. Things were pretty quiet in those days, but there were streetlights and we couldn’t believe nobody saw us.

I asked Norm if what he’d revealed could be mentioned publicly. “Yes, go ahead,” he said, “I don’t think they’ll be coming after us, now.” When I forwarded the story to Virgil, he recalled, “Yes, people used to say the gun should be turned a little and aimed toward City Hall.”

Virgil mentioned another story that supposedly took place about 1955. The Sheriff ’s Department had a call from a citizen that a cannon was being towed up Highway 101. Officers finally caught up with the cannon up to the campus and chained it to the vehicle in Orick, and made the culprits bring it back. After those incidents, he said they used a long pipe wrench and locked the brakes tightly, which are probably rusted together by now. Later, a museum in Oregon persistently tried to purchase the cannon, but the Legion wouldn’t let it go.

My original quest to talk to Marino wasn’t in vain. I contacted his daughter, Janet Kelly, to learn if she had come across any information in his estate. I commend her for the time she put into digging through the papers of a man who, I was told, “never threw anything away.” A couple of days later she called back to say she had found some information.

Indeed, Marino had contacted the Consulate General of Japan in San Francisco in 1995 and the Vice Consul, Koji Tsuchiya, had replied with information that confirms what I’d learned:

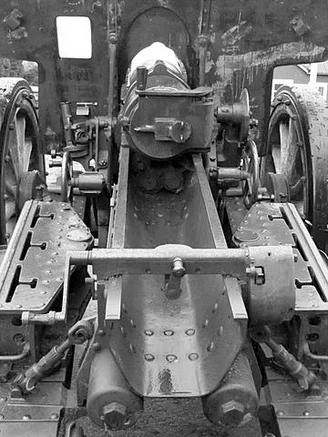

The Model 92 is readily recognized by its long slender barrel and tail (the entire gun is 27’ long, the barrel almost 16’), and it has been designed for long-range fire. Other distinctive features are the pronounced length of the sleigh and the three step interrupted thread breechblock. The recoil system is hydro-pneumatic. Mounted on heavily constructed wooden wheels with solid rubber tires, the weapon is normally tractor drawn but may be drawn by a 5-ton truck. It is capable of firing a high explosive (long pointed shell), chemical or armor piercing projectile. Time fuses are provided for the smoke, incendiary, and chemical shells. Total weight is 3,730 KG (8,206 lbs). In addition to the barrel being able to tilt upward to 45 degrees and downward 5 degrees, it could swing 36 degrees (right or left).

Additionally, the cannon had a range of about 18 km — something like 11 miles: Hello, Humboldt Hill! Greetings, Westhaven! — and the weight of a typical shell was 15.76 kg, or close to 35 lbs.

The Vice Consul must have contacted a fellow countryman, because a second letter from a Syogo Hattori, History Division, National Institute for Defense Studies, arrived in Marino’s mail several months later from Tokyo. It contained identical information, but added that because “the position of the center of gravity was considered, these cannons were towed by automobiles.” In addition, Mr. Hattori said, “Many type 92 cannons were used by the Japanese Army in WWII, including the Battle of Bataan, Philippines.” He did not know exactly where our serial No 136 was used during the war.

One question still lingered in my mind. Why is the second line on the breech, the “No 136,” in English? Earlier, one bit of false information had sidetracked me into thinking the cannon was actually British, supplied to British-held Singapore, then captured by the Japanese when they invaded China. The last line, the date of manufacture, is in Japanese — why use both systems of numbering? I decided to email Matt in Japan again. He replied,

As for the numbers on the cannon, after the Meiji Restoration in the 1860s, lots of ideas and technology from the West were actively sought out and imported. It was during this time that Arabic numerals made their way here. Even so, they didn’t completely replace kanji (Chinese writing system adapted to Japanese) numbering, which is still used today alongside Arabic numerals.

One facet I did not research is the stenciling in durable red ink on the breech close to the Japanese engraving. I can only guess the Z2 FMAR 198 was put there by our government to identify the artifact as it was requisitioned or entered our country. I felt I’d learned enough, though, and can let that question lie.

A cannon of the same model as Arcata’s cannon is seen in a tropical setting on a Japanese Wikipedia page. Photo: 不明 - [1] Taki’s Imperial Japanese Army HP, パブリック・ドメイン, via Wikimedia. Public domain.

###

The story above was originally printed in the Winter 2012 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE