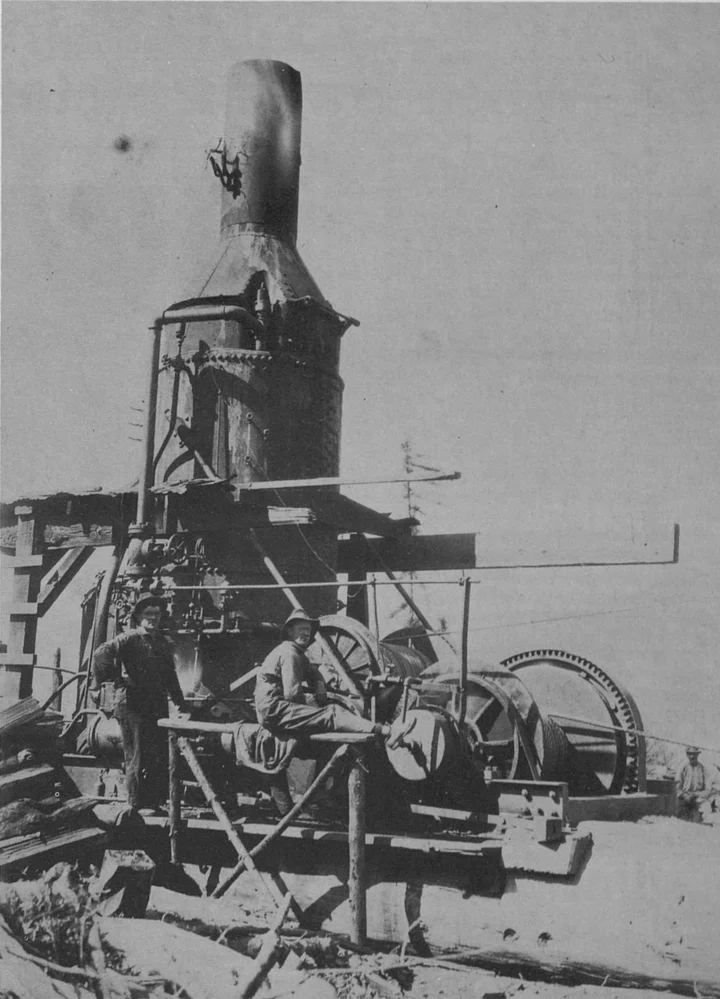

Logging scenes like this throughout the redwood area became a familiar scene as more Dolbeer engines were put to work. More men made up the crews and oxen became a thing of the past. This view is from the southern part of Humboldt County. Photos via The Humboldt Historian.

The donkey that finally ousted oxen from the skidroads of the West was not a beast but a small steam engine. It was called a “donkey,” after a ship’s auxiliary engine, because the man who invented it in 1881, a mechanical genius named John Dolbeer, had been a naval engineer before turning to logging. The loggers agreed with the name “donkey engine” because early models, though mighty, looked too puny to the loggers to be dignified with a rating in horsepower.

One day in August 1881, a mechanical monster smaller than any locomotive but bulkier than a yoke of oxen appeared in the redwoods near Eureka. It sat on heavy wooden skids and consisted of an upright wood-burning boiler with a stovepipe on top, and a one-cylinder engine that drove a revolving horizontal drive-shaft with a capstan-like spool at each end for winding rope. The power of this first steam donkey was small, so several blocks had to be employed to increase the pull; moreover, the hemp rope used was not overly strong and tended to stretch, especially when wet. These factors kept down the distances logs could be pulled. In addition, the design of this first model was such that the directions from which logs could be pulled were limited. Nevertheless, Dolbeer considered the tests a success and patented his invention soon after.

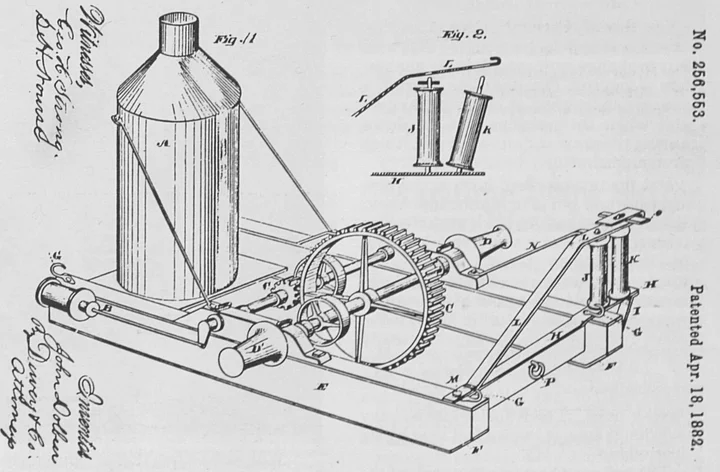

On Dolbeer’s maiden model, patented in April 1882, a manila rope 150 feet long and four-and-a-half inches in diameter was wrapped several times around a gypsy head: a revolving metal spool mounted on a horizontal shaft. The loose end was carried out to a log and attached to it. Then, with a head of steam built up in the high-pressure boiler, the spool revolved and the incoming rope hauled the log toward the donkey.

The Dolbeer Steam Logging Machine would be recorded as the greatest labor saver in the industry’s history and changed logging for all time. In a high lead setup with its steel cable running through a pulley near the top of a towering spar tree a huffing donkey could yank the mightiest log out of the woods in minutes, and a sharp crew could handle 5,000 tons of logs in eight hours.

ThÍs is the patent drawing for Dolbeer’s steam-powered engine.

Operating an early Dolbeer donkey required the services of three men, a boy and a horse. The “choke setter” attached the line to a log; an engineer or “donkey puncher”, tended the steam engine; and a “spool tender” guided the whirring line over the spool with a short stick. The boy, called a “whistle punk”, manned a communicating wire running from the choker setter’s position out among the logs to a steam whistle on the donkey engine. When the choker setter had secured the log to the line running from the spool, the whistle punk tugged his whistle wire as a signal to the engineer that the log was ready to be hauled in. As soon as one log was in, or “yarded” it was detached from the line; then the horse hauled the line back from the donkey engine to the waiting choker setter and the next log.

The horse was replaced by a simple improvement called a “haulback line”. The haulback line was joined to the main line, and the two were converted into a long loop, the far end of which traveled through a pulley block anchored in a tree stump. Out among the felled trees the choker setter fastened a noose of cable around a log and attached it to the main line; the noose “choked” the log securely when the line from the donkey engine grew taut and began to pull. When the log reached the yard and was released the haulback line pulled the main line over the spool and drug it back into the timber.

With at least two Dolbeer engines in action, scenes at landing became familiar, as logs were loaded aboard the short cars, foreground. This is in a Vance Redwood operation. Area not identified.

It is apparent that John Dolbeer gave the donkey engine its first real tryout in the Humboldt County woods. This item about “Steam Power” appeared in Andrew Genzoli’s “Lines From the Times,” a recopy from The Humboldt Times, dated July 31, 1881.

The report said:

Steam Power—It’s application to logging business: To those whoare familiar with the logging woods, or who have been accustomed all their lives to see the unwieldy ox-team tugging at the great logs, the announcement that steam power is to supersede this antiquated method will be received with no little surprise and incredulity.

But improvement is the order of the day and there is no reason why the ox team should not make the way for the steam engine as the stage coach has the engine.

George D. Gray of the Milford Land and Lumber Company has brought up from San Francisco and set to work on the company’s logging claims at Salmon Creek, a steam logging engine that bids fair to change very considerably our system of logging. The idea of such a contrivance was laughed at by practical men and when the machine was set down among the crew at Salmon Creek, it was pronounced utterly impracticable.

But the inventor had faith in the new machine and put it in motion last week. It has performed its work to perfection from the first and is now a regular hand in the Salmon Creek woods. The machine is designed to be used in blocking out roads, hauling out of the way all waste material and hauling logs into the roads and coupling them together ready for the ox team to take away. It consists of an upright boiler and engine. The crank shaft of the engine is geared into a “gypsy head.” The whole set on a heavy wooden frame, is twelve feet long by six feet wide.

The gypsy projects over one side of the frame. The weight of the whole machine with water and fuel is about four tons, and it has sufficient power to break a four-and-half-inch manila rope.

The operation of the machine is very simple. After running the rigging the same as for an ox team, a few turns of the line are thrown over the gypsy and the engines started. Besides being more powerful than the ox team, the power can be used or halted instantly. A log can be rolled up on its side and held there by the brake, to be peeled or “sniped”, or for any other work that may be necessary.

The machine is the invention of John Dolbeer.

Over the next decades donkey engines evolved far beyond the stage of Dolbeer’s initial fragile invention. Donkeys were mounted on barges to herd rafts of logs, “road donkeys” pulled logs along skidroads, and “bull donkeys” lowered entire trains of log cars down steep inclines. All of these descendants took advantage of another sophisticated invention: the wire cable, metal cable had been available since the Civil War, but Dolbeer did not use it with his early donkey engines because it kinked and often snapped. But manila ropes, especially when wet stretched and were too hard to handle for hauls of more than 200 feet. By the 1890’s strong steel cable, winding and unwinding on rapidly turning drums, gave the donkey engine a pulling range of 1,500 feet, along with the strength to do just about anything that needed doing in the woods. Loggers learned to “road” the logs hundreds upon hundreds of yards from one donkey to another along the entire length of the skidroad.

Donkey engines kept getting bigger and more versatile. There were two-drum and three-drum donkeys able to haul logs from the woods over high wires, donkeys that loaded logs on railroad cars, and landing donkeys that pulled logs to river or lake landings. In 1902 the donkey even became a steamboat. On Mendocino’s Big River, one lumber company launched a converted lighter with a donkey çngine that turned a stern wheel; christened S.S. Maru, it was used to herd large “rafts” of logs downriver.

Not all donkey engines were destined to be powerful midgets, born to turn the woods upside down — not when giants like these came onto the scene. Many of these great engines were built in Eureka foundries. Unless some reader with proof says differently, we are informed that the setting is southern Humboldt.

At first only the larger, more adequately financed logging operations used steam donkeys and similar power equipment but by the late nineties even the operators of small shows were coming over.

Considering costs, one logging operator commented about the donkey engine: “It don’t cost anything to keep it and you don’t have to feed it when it is not earning anything.” Steam donkeys not only got logs out of the woods more cheaply, they also made it possible to log when it was too muddy for bull teams to work. By the turn of the century, there were 293 donkey engines in use in Washington, 35 in Oregon and 61 in California. Thirty-five of the latter were in Humboldt and Mendocino counties. Though in time the donkey eliminated most of the horses and bulls, it gave jobs to many men. Before the coming of John Dolbeer’s spark-spewing marvel, a score or so of men might make up a logging crew; afterward, with production highballing along, a camp of 200 men or more was not unusual.

The donkey remained the power of the forests until the internal combustion engine arrived.

###

The story above was originally printed in the March-April 1982 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE