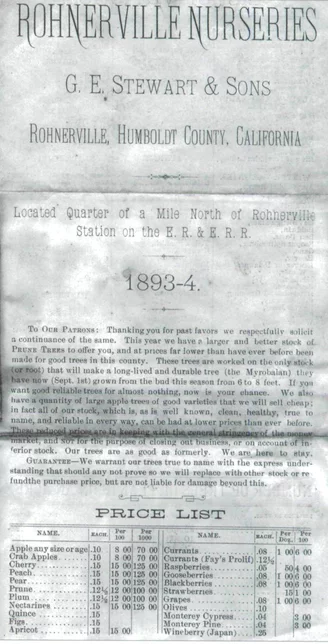

An advertisement in the Humboldt Business Directory promoting George E. Stewart’s Humboldt Nurseries. Click to enlarge. Photos via Humboldt Historian.

During the late 1890s and early 1900s, when agriculture thrived as a business in the valleys and prairies of Humboldt County, a good share of the rooted stock came from the nursery of George E. Stewart. He had a Rohnerville address and post office box. Today there is little evidence of the nursery that once advertised itself as the largest supplier of root stock “on the Pacific coast.” His ad in the Humboldt County Business Directory read: “All varieties true to label. I hold myself responsible for all mistakes that occur [and will] replace with other trees. My superior experience enables me to select varieties and species for different localities. Orders by mail, accompanied by M. O. [money order] receive same care as a personal selection.”

During his business trips to San Francisco, Stewart gave people he met glowing accounts of the soil’s fertility and the mildness of Humboldt’s climate. It was another matter to convince his neighbors that the fruit industry was profitable. They remained unconvinced until they learned in 1902 that Stewart’s farm averaged three hundred dollars an acre; a comfortable living at the time. The land, which Stewart had bought in 1885 for one hundred dollars an acre, was located on the northwest corner of Kenmar Road and Fortuna Boulevard, which was all pasture land then. It lay to the north and west across property now occupied by Pacific Lumber Company’s Fortuna log deck, and it extended south towards Alton and across part of Sandy Prairie.

Professor J. M. Guinn visited Stewart’s nursery and wrote about it in 1904:

The county is fruit producing … apples and cherries predominate without irrigation. The output from … Rohnerville farmers is now 70,000 to 100,000 boxes … and a very high grade product… it is safe to say that no individual has more credit due for the present status of the industry than George E. Stewart. The headwaters of Strong’s Creek is five miles above Newburg Mill I which was located at the eastern end of present Newburg Road] promising a goodly supply of water, and the Campton and Jameson Creeks are nearby and tlow into the Eel River [these creeks cut across Stewart’s property]. Trees of willow, alder and cottonwood line the creek banks …

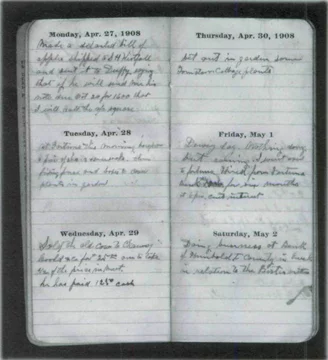

Stewart used small datebooks to record everything from financial transactions to work in his vegetable garden. This 1908 calendar is one of eighteen books archived at the Humboldt County Historical Society.

It took time and work to build such a profitable nursery. Stewart’s notebooks give us examples of the work involved:

Dug potatoes all day and sacked same [by hand, remember]. Boys helping [a later note mentioned the youngest boy started to school[. Cleared fence of blackberries. Dug trees for sale to Frank Shaw. Jacob Ackerson. and Rev. P. Henneberry | the priest of Mount St. Joseph Academy, which was located on the bluff above Alton, where pupils studied seven languages beside the usual academic studies]. Set Cypress trees for windbreak |Eel River Drive, Fortuna]. Attended first meeting of the Humboldt County Horticultural Society. Came home, put up shelves in the house, made nursery stakes.

Besides the work at his home and nursery, Stewart took on jobs for neighbors to earn extra money. He noted constructing a bridge, and also dug wells. One was for the Newburg Mill: “finished well for George Cousins [superintendent of the Newburg Mill], went down 68 feet. Trimming and hoeing in the nursery, south of the creek, budding prunes. Invented my Gravity Gate.”

Then, as now, there was a constant worry about rising flood waters. Stewart’s 1890 diary reflects his concern:

Jan. 22 … Rain and hail, cold, disagreeable. Jan. 23… creeks overflowing at the road tonight. River is reported rising fast. Jan. 24 Rain continues, water well up. River continues to rise… . Went to see |it[ this morning. Jan. 25 … River out of bounds, backed in a little on the NW corner of my place. Feb. 3 Creek[s] overflowing their bank]s[. Higher now than before. This being the fourth time this winter water is over most of my orchard, south of the creeks. Feb. 4 … a number of landslides are reported by the Rail Road, one at Collidge ]sic| hill, one at Rowley, one below Singley’s. and a large one the other side of the Van Duzen.

Finally, on February 6, relief came. Stewart recorded that there had been no rain that morning, and then in what must have been a later entry, adds emphatically “No Rain Today.”

The railroad mentioned, the Eel River and Eureka Railroad, had been built by lumbermen John Vance, William Carson and others. It ran from Eureka to Alton and beyond to the Van Duzen River. Farmers in Stewart’s region shipped produce to Eureka on the railroad; produce then went by steamer to San Francisco markets.

Pests in the nursery were another worry that Stewart shared with today’s farmers — there was a steady battle to ward off the ravages of insects and bugs. Stewart records his attempts at controlling them:

Carbolic soap is no good for pear slugs. Today dusted slugs with lime. This is effective. Sprayed some trees with brine that would float an egg, see the results later.

Another problem was fungus. His recipe for that was:

6 ounces of glue dissolved in one or two gallons of water, by boiling. Dissolve two pounds of carbonate of copper, mix this and add fifteen gallons of hot water. Dilute with cold water to make fifty gallons.

He called it very effective.

A price list from 1893-4, when Stewart’s business was called Rohnerville Nurseries, offered apple trees for the bargain price of ten cents. Merry Jane Dinsmore Collection, via the Humboldt Historian.

In Stewart’s day, county roads were kept in shape by the landowners who used that particular road. They took tums doing maintenance work, and each man paid a poll tax. Stewart worked out his poll tax on the county roads he used by hauling gravel and was exempt for further work “on account of my age.”

His finished potato yield was 380 sacks. The greater proportion of crops went from the county by steamer, but after 1914 farmers used the cars ofthe Northwestern Pacific Railroad.

It was not all work and no play for Stewart. He was also active in social events. One of his entries reads: “Attended the inauguration of Grover Cleveland.” Cleveland was the working man’s choice, which dates the event at 1885. A more sensational political event was also reported: “[We] bumed powder at Rohnerville which is the first Democratic demonstration in the history of the town.”

Burning powder meant they fired an anvil, a popular way to celebrate. Stewart may have done the firing since he knew blacksmithing. It was done by pouring a circle of black powder on a large anvil, and placing a small anvil on top of the larger one. A trail of powder was dribbled down a board to the ground, and a man skilled in the work lit the trail to fire off the anvil. The goal was to make the smaller one rise high in the air and then settle straight down on the larger anvil. If it was a particularly good rise people would talk about it for years afterwards. Men who used the explosive were called powder monkeys. The skill was used to blow out stumps during the early days of logging in the county. A good powder man, like Alex Beattie, of Alton, could blow out a huge stump and not jar anything near it. Beattie, however, lost the ability to smell.

For Stewart, life went on: grafting, budding, digging trees for sale, harrowing fields, sowing seed, building on the house and sheds, making trips to Blue Lake (his daughter Lizzie had married Dr. G. B. Marvin), on to Korbel, and while he was out that way, to visit lumberman John Vance, who had put in an orchard at Essex of one hundred acres of apple trees bought from Stewart. They estimated Vance’s profit would be in the ten thousand dollar range. Stewart would drive his buggy to Bald Mountain to visit Jim Blake, and then on across the Hoopa Valley to Weitchpec before heading for home. Later that same year he went to Phillipsville to Frank Sallady’s ranch to put in an irrigation system (his daughter Clara had married Sallady).

Another time he drove to Blocksburg with William B. Dobbyns and spent the night with George W. Norman (Dobbyns, Norman, Benjamin Blocksburger, and Isaac Price had all fought in the war with Mexico and all four had ended up in Humboldt County.) Stewart records: “Norman, at Larriby [Larabee], wants 16 peach trees, 8 early, and 8 late, of my own selection.”

On July 24, 1892, he wrote about seeing a balloon ascension in Rohnerville.

Stewart was descended from the line that claimed Queen Mary of Scots. George’s branch of the clan, being non-Catholic, had moved from Scotland centuries before to avoid religious persecution. George’s father, William, came to America and settled in Cutler, Maine. In 1838 William moved his family to Illinois (considered the far west at that time), and bought 200 acres for a nursery. William died in 1857, leaving a family of ten sons and four daughters. He was a staunch Whig.

George started out as a Republican, but switched to the Democrats in time to vote for the second term of Ulysses S. Grant. [Ed. note: Unclear what the author meant, here. Grant was a Republican.] When he was old enough to be on his own, George went to Saginaw, Michigan, where he worked as a blacksmith, went into partnership in a mill, and bought acreage for an orchard. At the age of 22, he married Jeannette W. Duncan on Nov. 5, 1857. While in Michigan, George had joined the Masonic Lodge, and continued his membership when he and Jeannette moved to Humboldt County. He was a member of the Eel River Lodge #147, F. & A. M. of Rohnerville. He was also a founding member of the Humboldt County Horticultural Society, and one of that group’s first presidents. He was later elected to the Humboldt County Board of Horticultural Commissioners, where he served a term as chairman.

The Stewarts were hospitable people who often had friends stay overnight, or come to dinner and stay overnight. Roads were rough and winding, and it took almost a day to travel by horse and buggy from Blue Lake to Fortuna. Stewart’s notebooks are full of these impromptu dinners and church affairs: “July 21, 1889 … wife and Wellington [a son] went to the dedications of the Presbyterian church at Grizzly Bluff … Professor N. S. Phelps called and stayed overnight… J. H. Oliver and wife here for dinner … Mr. Dobbyns [William B.] and wife here to dinner.” At another time, Stewart and Dobbyns took their wives to Port Kenyon on a fishing trip: “Had a good time and had good luck, too.” Other guests were listed: “William Taylor and mother visiting here, stayed the night. Jim H. Blake of Blue Lake came on the 12th and stayed until the 14th.”

Stewart was a tall man and wore a black hat when outdoors. He often did neighborly tasks for Father Henneberry of Mount St. Joseph’s Academy. Stewart sold the priest his patented gravity gate and gave permission for the priest to make as many as he needed. On one occasion he wrote he “went to the school and fixed the priest’s gate.”

One hundred years, produce was preserved in a variety of ways. It was stored in cellars, bins, and coolers that were in the kitchen. To create a cooler, a burlap-covered wire cage was fitted into an empty lower window frame. Water dripped over it, cooling the contents. Another way to preserve was by pickling. Stewart includes a recipe he evidently used for eggs:

4 gallons of boiling water, 1/2 peck of new lime. Stir well for awhile and strain. Add 10 ounces of salt, 3 ounces of cream of tartar. Mix. should stand two weeks before using. Pack with large end of the egg down, cover with the mixture. This will protect them for two years.

Life was not all success; the Stewarts knew tragedy. Jeannette died March 27, 1903, and was buried in the Masonic Cemetery at Rohnerville. She left a family of four children: Lizzie Marvin, Frederick W. Stewart, Wellington W. Stewart, and Clara Stewart. One son, Fred, was an epileptic and drowned in a creek by their house. Their first son, Lucius, died in 1892 in Michigan. Stewart married a second time to a longtime Michigan friend, but after living in Fortuna two years she returned to Michigan. Stewart family members were blamed for the breakup.

George E. Stewart, friend of the famous Luther Burbank of Santa Rosa, and of Albert Etter of Ettersburg, died September 21, 1919, at his home and was buried in the International Order of Odd Fellows Cemetery at Rohnerville. All three of these men were in the nursery business and patented many new species of plants.

The property owned by Stewart was sold off by his heirs, who had no wish to keep up the nursery and orchard. Clara Stewart Sallady Dinsmore built a home close to the home she grew up in. At the present time, Clara’s house and the one her father built are still standing, separated by Fortuna Boulevard’s four lanes of traffic. Clara’s house is the chrome yellow house opposite the white two-story home built by her father.

Progress has not eradicated all signs of the nursery. The row of Monterey pines and cypress trees still stands, shading Eel River Drive along the railroad tracks that parallel Highway 101. The fragrant apple orchard is gone, and so is the nursery of growing plants. But Stewart’s notebooks survive, and climbing plants still shade his house, a sad reminder of what used to be.

Caption from 1998: “Stewart’s house still stands at the northwest corner of Kenmar Road and Fortuna Boulevard.” Merry Jane Dinsmore Collection, via the Humboldt Historian.

The same house today, across from the Starbucks in Strongs Creek Plaza. Google Street View.

###

The story above was originally printed in the Winter 1998 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE