Left to right: Priscilla Shepherd, Marian Connick, Naida Olsen, Tiny Lindgren, Marianne Jensen, Lola Austin, Violet Lund, Maryellen Keating, Jessie MacMülan, Lois Carlson, and Wilda Lindgren. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

A few days before Christmas 1944, after months of stomach problems, my father died of cancer. My mother, my two sisters, and I were devastated. We came home from the funeral to a house empty without him.

I had celebrated my seventeenth birthday less than a month before he died. One would think that with a war on. 1 would have been independent and worldly, but that was not the case. I missed my father and worried about how my mother would manage without him. 1 was shy and myopic; not part of the “in” crowd at high school. I graduated from Eureka High School in January 1945, and I did not know what to do with myself after graduation. Mother suggested I enroll at Humboldt State College. With most of the young men still fighting in World War II, about 145 of the 159 students enrolled at HSC were girls. The rest were boys under the age of 18, men not eligible for the draft, and one or two men over 65.

I knew of only one family member who had graduated from college — my mother’s younger sister, Sadie Phillips. Later. I learned that two cousins on my father’s side of the family, Anita and Ruth Shaw, had also attended Humboldt State.

Perhaps mother let me take the car that day, a 1941 olive-green Ford Deluxe sedan. I found the school, where arena registration for the spring semester of 1945 was in progress. I muddled through and paid the fees, my ears ringing with the echoes of voices, footsteps and dropped books in the poor acoustics of the gym.

Nearly all of the classes were held in Founder’s Hall. But some classes for prospective teachers were held down the hill in the College Elementary School, where student teachers taught under the guidance of supervising teachers. The gym was behind Founder’s Hall. Nelson Hall, a co-ed dorm with one wing for girls and one for boys, stood below the parking lot.

Most of my classes were easy to find. English 101 and Speech 101, both taught by John Van Duzer, were on the second floor at the south end of Founder’s Hall. World History was in a lecture hall tucked away behind the auditorium on the ground floor, north. Health class on the second floor overlooked the front entrance of the building. The rule that class was canceled if an instructor was fifteen minutes late pleased us all, and the Health teacher was usually late. We sat poised, ready to leave, as the clocked slowly ticked to the quarter hour. The women’s lounge, a “girls only” sanctuary, was a place to go between classes to study, eat lunch, talk, or smoke - but none of my friends or I smoked. No boys allowed - even if there had been any.

At the south end of Founder’s Hall was a wooden structure, flanked by a wooden sidewalk. This building housed industrial arts and crafts — woodworking and pottery — the domain of Horace “Pop” Jenkins, who seemed frail and elderly to me then, and who must have been there when the college first opened its doors in 1913. Everyone, students and faculty alike, called him Pop.

Across a patch of worn grass and another wooden sidewalk, a second wooden building housed the Student Union and Book Store — the Co-op. A soda fountain ran down the center of the Student Union, where a scoop of ice cream was a nickel, and a squirt of chocolate syrup, one cent. I longed for one of those chocolate sundaes, but 1 didn’t have six cents to spare, and felt I could not ask my mother, so recently a widow, for extra money.

At Humboldt, I felt I had arrived where I belonged, no longer on the outside looking in. I made friends with a large group of girls, all of whom lived at home and commuted to school. Some had cars and others rode the bus — the Humboldt Motor Stage. The bus company ran one bus, a “modern,”snub-nosed vehicle driven by Ralph Mackie all the way from Fortuna; this bus reached the campus at 9 a.m., too late for eight o’clock classes.

The bus I rode left Eureka at 7:30 and reached the college by 8:00 a.m. I had to get up at six, dress, cook a little oatmeal for my breakfast, pack a lunch, and make sure I had my bus pass, which cost five dollars for one month. I walked four blocks in the dark from my house to the corner of Harris and E Streets and waited with a few other students by the big wooden water tanks for the bus.

The Humboldt Motor Stages bus from Fortuna, at the Greyhound station in Eureka on 4th Street. Left to right: Naida Bartlett, wearing her “Dutch girl” shoes: the bus driver. Ralph Mackie; and another student, possibly Pod Gushaw.

The old bus finally got there, limping along on what were probably worn retreads. New tires were not available for civilians in early 1945. The dim glow of its parking lights, the only vehicle lights allowed at night during wartime, barely penetrated the gloom as the bus poked its long hood out into the morning mists. The driver, a college student, drove with care, aware that his ancient chariot had to last until the war ended. Brakes screeched as the bus stopped. The door swung open. I stepped into the murky gloom and found a seat. A musty odor permeated the interior, as though it hadn’t been cleaned for some time. A few students studied by the feeble glow of small lights recessed above the windows. Others dozed as the bus ratcheted down E Street. We made a few more stops before heading east on Fourth, a two-way street then, and part of Highway 101.

The asthmatic bus wheezed out of town, over the drawbridge at the slough, and along Highway 101, past what were stinking mudflats a low tide or wetlands at high tide, past the small airport at Murray Field, and the eucalyptus windbreak edging the bay. We hit the legal speed limit of about thirty-five miles an hour by the time we entered Branard’s Cut, a high cliff of red-ochre dirt carved with the initials of dare-devils who had had to hang over the edge or climb up the side by sculpting hand- and footholds.

A diner, Ma’s Hamburgers, nestled at the base of the cliff. A dirt road wound up the back of the cliff and led to a lovers’ lane at the top. but I didn’t know about this until years later when my future husband, Ken Gipson, took me there to study the stars.

The sun broke over Fickle Hill and threw a rosy glow across the duck blinds on pilings in the tidewater. We passed the Samoa Road and the Red Robin Café, and entered Arcata. The driver down-shifted as we headed up the hill by Safeway, the Bank of America, and the Ford garage. He shifted again, and we passed the plaza with the Varsity Sweet Shop in the middle of the block on the right, and the Arcata Union print shop on the corner. The Hotel Arcata was across from the plaza’s northeast corner; Brizard’s Department Store, across from the southeast corner; and a statue of President McKinley in the center of the square. Another hill loomed; another downshift - gears grinding. We got a running start past the bakery and turned up Humboldt Hill. When the bus lugged down, the driver shifted to the lowest gear, and we crawled up the grade to the college, the engine complaining all the way. The old bus came to a stop in front of the steps to Founder’s Hail beside a bench donated by the class of 1933.

Among my new friends was one old friend from Eureka High, Lola Austin (Larson). She and Maryellen Keating (Householter) took pre-med and both went to St. Mary’s nurses training school in San Francisco and later had successful careers as nurses.

New friends included Wilda and Tiny Lindgren,who drove to school every day from Trinidad; Géraldine Stanbury. a red-headed girl we nicknamed “Pinky,” who had her own car; and Louise Meeks, Jessie MacDonald, Priscilla Shepherd. Naomi Schmidt. Marianne Jensen (Schroeder) known as “Toodie,” and a girl named Gladys we teasingly called “Happy Bottom.” Lois Carlson majored in education and eventually became a supervising teacher at the College Elementary School. Vicki Short (Hartman), who had enrolled at Humboldt State when she was only fourteen, later taught at Lincoln and Marshall schools in Eureka. Marian Connick taught in Stockton. Violet Lund (Oppenheimer) taught in Sun River, Oregon. And I discovered another Naida - Naida Bartlett. Naida B. and Naida O.

Naida B. wore wooden-soled “Dutch girl” shoes, and wrote with a fountain pen in brown ink. I’d never known anyone with my name before, nor anyone who wrote with anything other than blue ink. We became best friends. Naida and I decided to become kindergarten-primary teachers. She later taught in Rohnerville, and I eventually taught at McKinleyville, Whitethorn Valley and Rolph School in Fairhaven and substituted at the Samoa School.

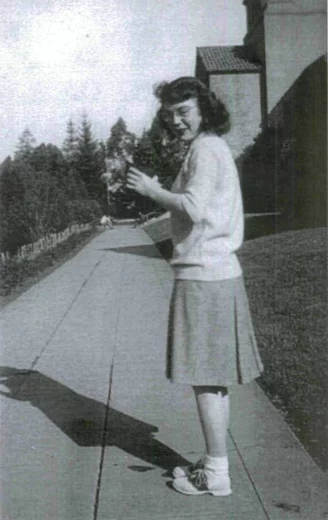

The author in the spring of 1945, on her way to class at Humboldt State College with her Brownie box camera.

Fred Telonicher taught zoology in the lab at the back of Founder’s Hall. Jars of specimens pickled in formaldehyde sat on top of the cupboards. For a girl who had been raised on the perimeter of the Victorian era, when girls were not told the facts of life, zoology was a scary revelation.

The major project was the dissection of frogs — huge frogs, not little green tree frogs. My frog was sixteen inches long with a fat tummy, and it was stiff and stinking from the formaldehyde that wrinkled the skin on my fingers. I picked up the scalpel, turned my face away, took a deep breath, held it. turned back, and cut. Tiny black and white dots popped out. I had no idea what they were. I looked at Lola’s and Maryellen’s frogs. They did not have black and white dots.

Mr. Telonicher walked through the lab. and 1 asked him what the dots were. He gazed at me for a moment and said “Eggs.” Then he moved to another table where. I assume, he expected to get more intelligent questions. Eggs. Oh. Well, that would explain why my frog was so fat. It didn’t explain why I was so ignorant of life.

Our young, dedicated P.E. teacher told us to interpret the music for modern dance with long, filmy scarves, waving them around, and dancing to whatever the music made us feel. We ran back and forth across the gym, our scarves floating in the air. Since the age of five I had learned precise dance steps and routines. I was too inhibited to modern dance.

I will never forget the librarian, Helen Everett. Mrs. Everett spoke in a soft voice as she introduced the children’s literature class to A.A. Milne’s Winnie-ihe-Pooh. I can’t thank her enough. To this day, Winnie-the-Pooh and The House at Pooh Corner remain my all-time favorite children’s books.

Stella Little taught arts and crafts: water color painting, knitting, basketry. These credits went toward a minor in art. Mrs. Little’s classroom was one of the light, airy, second-story front-facing rooms in Founder’s Hall.

Because a few girls had cars, we had some mobility, as long as we could get rationed gas. We didn’t go far: Mad River, up the coast to Luffenholtz Beach, and. once in a while, if we had any money, to the Varsity on the plaza for ice cream.

I had such a good time at Humboldt that I became one of the rare third-semester freshmen. Cutting speech class whenever it was my turn to give a speech was not the smartest thing to do. A lot of students cut health class, especially in nice weather. My friends and 1 would take our triangular first-aid bandages from class and our sack lunches, and go up Mad River to swim under the railroad trestle. Triangular bandage swimsuits covered more bare skin than today’s bikinis. Even so, in 1945. they were quite daring — rather shocking, in fact, as they were nearly transparent when wet. Fortunately. there were no boys around. We’d have simply died if anyone had seen us in our makeshift swimsuits.

The war ended in August of 1945. No more worrying about a telegram announcing the death of a loved one. No more gold stars in the front windows. No more gas rationing. No more shoe or butter or meat rationing. Our service men and women were coming home. We could settle down to a normal, happy life.

Or so we thought. We had no inkling of the explosion that was about to take place in our small “girls’” school. The G.I. Bill of Rights would change our school, and our lives, forever.

###

The story above was originally printed in the Fall 2004 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE