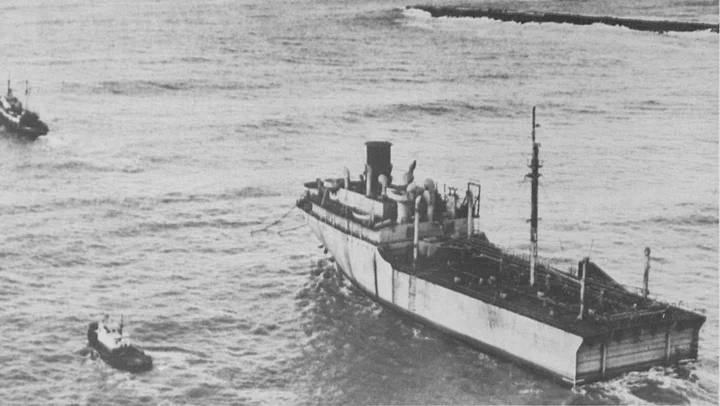

The half-a-ship, “Donbass III,” being towed stern first, heads out of Humboldt Bay on its last voyage. The destination was Los Angeles Harbor and the scrap pile. Photos for this article from the Martin and Rynecki Collection, via the Humboldt Historian.

On a quiet January day in 1959, the Donbass III crossed the entrance of Humboldt Bay outbound. There were a few interested people watching as two tugs guided the vessel, one towing and the other running alongside. When they reached the open sea, the second tug would return the bar pilot to Eureka. Looking closer, observers noticed the ship was proceeding under tow, but backing. Why, and for what distance?

Watching with keen interest, in addition to the Coast Guard, were several persons on one of the jetties. An observer might have seen among them Tom Jenkins, Division Manager for Pacific Gas & Electric Company. And high on Humboldt Hill, where he could command a view of the entrance and a broad expanse of the Pacific to the south, stood George J. Rynecki.

Before learning why there appeared to be an air of excitement about Ryneki and others, we should note a few details of the ship that was starting on its final voyage. Construction of the ship was done in the Swan Island shipyard, Portland, Oregon, in late 1944. She was designed as a tanker of the T2-SE-A1 type, one of many that the USA had built for the war effort. At her christening, she was named the Beacon Rock, a turboelectric ship with a name that was to be hers for only one year.

The War Shipping Administration was acting as owners and operators of our Merchant Marine fleet and under terms of the Lend-Lease program the Beacon Rock was turned over to Russia. They changed her name to Donbass III. (This was the third ship the Russians named honoring the coal basin of the River Don.) The Russians put her to work importing U.S. war material from West Coast ports.

It was in February, 1946, that the Donbass, bound for Vladivostok, encountered a violent storm. The Russian seamen know these waters well and how wild the icy seas can be but there seemed to be more than the elements stacked against them on this fateful day. The decks were loaded with planes and tanks and the cargo holds bulged with aviation gasoline and fuel oil. They had reached a point off the northern chain of the Aleutians, where seas were running high and it was a bitter, cold, foggy day. Experienced sailors agreed they had never encountered such a vicious clash of the elements. Each hour brought an increase in the storm’s tempo.

(Murl Harpham, writing for Humboldt readers, in a local newspaper, described the way the ocean hurled the Donbass’ 10,000 tons of deadweight around that day,…”like a redwood chip in the maelstrom of Ishi Pishi Falls.”)

There was no mercy given the ship. She was being brutally tossed in all directions — a ship nearly the length of two football fields! Her boilers were still generating steam but the question was, how much longer could she continue taking such punishment in such a mean storm.

The sequence of events of the next few hours is unclear. However, when the battering ended and the sea subsided 48 hours later, there was only one half of the ship afloat. The 280-foot-bow section, cargo. Captain and over a dozen crew members had been claimed by the sea.

Several theories were postulated regarding the cause of the disaster. There were suggestions that varied from an explosion of a floating mine to a rupture of the ship’s seams due to the twisting of the vessel during the storm. We know the condition of the seas she had gone through and of the possibility that she may have been overloaded. It is acknowledged this was not the first ship to suffer a like casualty.

The late Humboldt County historian, Andrew Genzoli, gleaned the following for his column, RFD: “Days later (following the storm) crewmen of another U.S. tanker, the Puente Hills, sighted the floating stern section and took it in tow. For 21 days they battled stormy seas to bring their prize to port. Their claim of salvage was upheld. The Shipping War Administration, owner of both ships, paid $110,000 to buy back what was left of the Donbass III” (About fifty persons were rescued from the broken ship.)

At the close of W.W. II, population growth was particularly noticeable on the West Coast. Power companies were hard-pressed for additional power to meet the demand for the industrial boom and Humboldt County was no exception. There were thirty or more industries needing electric power near Humboldt Bay and several hundred throughout the county. One possibility explored involved bringing to Eureka a gigantic “Mountain-type” locomotive to power a generator for additional electrical energy. But this proved out of the question because the Fort Seward tunnel was too small for the locomotive.

Eureka had an immediate need for additional emergency power. Winter gales had been causing frequent interruptions of service. During those years there was only one line over the mountains from the Cottonwood Substation. News of a half ship that had been towed into Seattle, Washington, suggested a solution to the problem. A bid of $125,000 was submitted by P.G. & E. at a Maritime Commission sale. Immediately upon notification of their successful bid, arrangements were made to get the ship to Eureka.

It certainly seemed the ill-fated ship had an affinity for storms. Two tugs started out from Seattle with her. They were only as far south as Umatilla light when they were hit by a windstorm that threw their towing apparatus into what first appeared to be an impossible situation. The tugs were successful, however, in getting their tow into the harbor at Port Angeles where repairs were made. Following improvement in the weather and a change in luck, they were able to reach Humboldt Bay on November 3, 1946. Six days later the ship was nestled into her position at the foot of Washington Street. Within a few weeks she was ready for steam-up and for her huge generator to feed power into the P.G.&E. system, a job it performed for the next ten years.

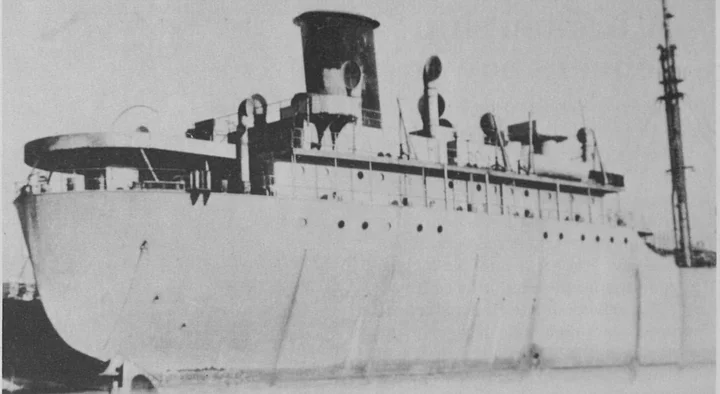

A close view of the stern section of “Donbass III,” the area housing the generating machinery used by PG & E while the vessel was in Eureka.

Before getting into operation, a number of things needed to be accomplished. The ship had to be secured so storms would not disturb any connections of the heavy duty conductors that were brought up through the ventilator, over the side and then tied into the system. PG&E Life, a magazine for men and women of that power company, reported that:

… the cargo tanks were filled with oil to supply the nearby Eureka Station B and the Donbass III herself. The added weight grounded the ship in the mud, an ignoble end to a once proud vessel. But her usefulness to P.G. & E. was just commencing.

The engine room was given a thorough overhaul, both boilers and her immense generator. Normal full load was 4,800 kw, which could be raised to 5,500 kw during periods of emergency. Over the years many workers served faithfully in that engine room. A few of those employees of P.G. & E. known to the author were: Howard Taylor, Red McCormick, Jim McMillen, Barney Koli and Ed Weeks, who went from there to eventually head up the electrical engineering at Humboldt Bay power plant. (It is reported that some of the men, leaving the engine room to go topside on a cloudy, moonlit night, experienced the feeling of actually being at sea. The same feelings were felt on a stormy night when they climbed up from the engine room to go ashore.)

After ten years, the advent of more and better electrical facilities in the Humboldt area made the Donbass again ‘war surplus.’ Before the ship was sold, the main generator was rebuilt and shipped by P.G. & E. to Vallecitos. There in the land-locked hills of Livermore, it turned out the first privately financed atomic electric power in the nation. Thus, the least of all P.G. & E.’s steam units became the bellweather of a new era in power production.

Marine historian Wallace Martin has an advertisement in his file that appeared in “The Marine Digest” early in 1957 in which it states that Captain H.A. Jeans & Associates, Marine surveyors of San Pedro, were offering the ship for sale. But ships and portions of ships were plentiful, so the Donbass III was to sit many months until the company decided to offer the ship as scrap. Contacts were made with several firms on the Pacific coast, suggesting they might consider entering a bid. One of these was George Rynecki of the local firm of G. & R. Metals.

When George Rynecki learned of the ship auction, he debated about making a bid. He concluded that this would be a project of such magnitude it would be best to contact a specialist in scrapping ships. Perhaps after consultation, a partnership could be arranged. In our interview with Rynecki, he explained there were several firms that made a specialty of dismantling ships for scrap, so he searched them out.

An agreement was reached with the National Metal Company of San Pedro to join in the purchase of the tanker Donbass III. In their agreement, the responsibilities for Rynecki were to enter the bid, refloat the ship, make it seaworthy, make any minor salvage at Eureka that seemed wise and expedite the towing arrangements for transport of the ship to San Pedro, where the major salvage would take place.

Simple and straightforward as the foregoing sounds, it was one problem after another that had to be resolved. Power had been disconnected, so G. & R. Metals hooked up a diesel-powered generator that was tied into the ship’s own lighting system. Climbing up and down five or more decks to work was not practical, so a door and passageway was cut through the hull. Several tanks were loaded with seawater that would have to be pumped out to free the ship — later they were to find that an opening the size of a large door had been cut through a hull section below the waterline. They were unaware of this for some time, therefore pumping was futile and the opening had to be located and sealed.

Not every problem was discouraging. They found several diesel engines that they were able to start with remarkable ease and these could be used for generating power for such chores as lifting,, lights, welding and cutting. Arrangements were made to have P.G. & E. bring electricity to the ship, thereby allowing the G. & R. Metal crew to bring in several large pumps that Rynecki owned. These were used for pumping seawater back and forth, to aid in freeing the ship and later for the transfer of ballast in trimming the ship so that she would maintain an even keel for the impending sea voyage.

Rynecki expressed admiration for the job that his foreman, Louis Thomas, did in the preparation of the vessel for sea. Thomas was experienced in salvage and understood working with various metals and had a “take-charge” attitude.

As the ship was prepared for the trip, minor salvage was done, but Rynecki was pushing his men to reach a deadline. He learned that one of the highest tides of the year was to happen soon. Inasmuch as the ship had not been free of the bottom for many years, help from the elements was welcome. The best tides were around year end. They missed the first one, but were ready for number two. Work went along at an eager pace. The plan was to tow the ship from her comfortable berth to a neighboring dock. Rynecki had arranged with Coggshell Company to have two of their boats on hand at the appointed time.

The moment of truth arrived. The tugs were on the scene and a small line was thrown to the ship so that Louie Thomas, who was waiting on the deck, could pull the towing cable and make it fast to the ship. On shore, a D-8 Caterpillar tractor was hooked up ready to pull its winchline simultaneously with the tugs when the signal was given. There were still unanswered questions: When it got loose from the bottom, how would it ride? Would it be heavy on bow or stern? How high in the water would she be?, etc.

Rynecki surveyed the preparations and gave the prearranged signal for taking up slack and to standby. Was it imagination? The ship seemed to be ready to move! This was the moment, pull! The tugs dug in and the “cat” roared. With hardly a shudder, the ship was free and riding remarkably well. A real cheer was given by workmen as the ship moved into the bay on the 31st day of December 1959.

New Year’s morning Rynecki drove to the dock to see how the Donbass III had weathered the night. From a distance she looked in good shape but on closer examination Rynecki was horrified. The ship was riding with a list. Was this something that might get worse? Would it be a gamble to assume there would be no change in the status quo for another twenty-four hours? The wise move seemed to be to locate Foreman Louis and ask him to spend a few hours of his holiday trying to trim the ship. Things worked out well that day, but it turned out to be a pattern that had to be followed each day, even though there was steady improvement in the attitude of the ship. Advice from one who was seasoned in such things was to load ballast, thereby lowering the freeboard to improve her ride. This suggestion proved to be sound, but it took time with the equipment that was available. Finally the call was given for the sea-going tug to come to Eureka.

A very powerful tug with an experienced crew arrived to move the ship to Terminal Island, Los Angeles Harbor. The transit was accomplished with no problem. There the massive boilers, her shaft and other large machinery were salvaged before the complete dismantling took place.

George Rynecki said, “That part was not my worry, I had to get her safely out in the ocean. What a relief that was to see her cross the bar so smoothly!”

Since that day, there have been at least two occasions elsewhere in the world when a ship’s power plant has been used as emergency power for a seaside community. However, we are certain nothing can match the record of the Donbass III, while anchored at Humboldt Bay.

Before breaking in half, the Donbass III looked like this sister ship, the Allatoona, the world’s most numerous tanker type. A total of 481 were built by U.S. shipyards.

###

The story above was originally printed in the November-December 1986 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE