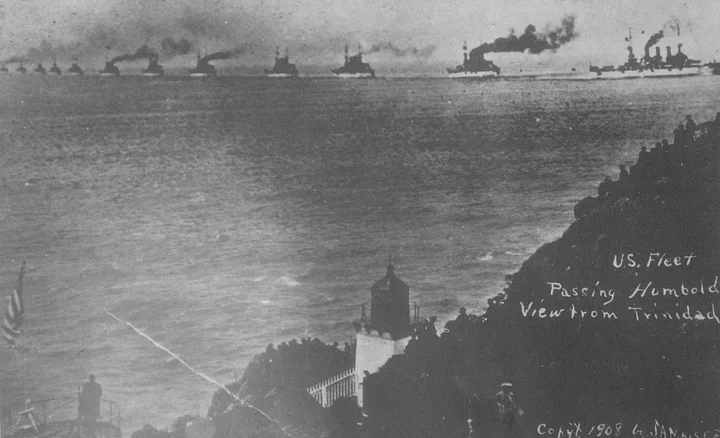

On May 19, 1908, the “white glory of the Navy” — 16 battleships of the Atlantic fleet — passed the Humboldt coast on its grand parade around the world. Photo by J.B. Meiser, via the Humboldt Historian.

The Great White Fleet of the United States Navy left Hampton Roads, Virginia, on December 16, 1907, with the greatest display of naval power ever assembled for a world cruise.

With gun and brass reflecting the sun’s rays like mirrors and the signal flags snapping in the wind, 16 white battleships made for the open sea.

President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt aboard the Mayflower, the presidential yacht, signaled the flagship Connecticut with Rear Adm. Robley D. “Fighting Bob” Evans in command — to “proceed upon duty assigned.”

The President wanted “young and vigorous lads” to man the ships — they would be the “torch bearers.” From the central plains states came sailors who had never seen the ocean, and from all over the Union came young men to answer the newly coined phrase “Join the Navy and see the World.”

Aboard the 16 battleships were 24 grand pianos, 60 phonographs, 300 chess sets, 200 packs of playing cards, and equipment for handball and billiards, plus 200,000 cigars, 400,000 cigarettes, and 15,000 pounds of candy. Each ship had a library, a stage for theatricals, sheet music for group singing, nickelodeon peep shows (censored), and, in the ship’s canteen, ice cream and soft drinks. No rations of liquor, or grog, had been permitted aboard since the Civil War.

The purpose of the voyage around the world was to impress the world with American naval might, as well as to check on Japan’s growth and expansion in the Pacific, since rumors abounded that the United States was about to enter a war with the Japanese.

The voyage of the Grand Fleet was heralded by the international press and followed by American newspapers with unwaning interest.

The Great White Fleet circled South America stopping in all major ports to wild enthusiastic receptions. Passing the Isthmus of Panama (the Panama Canal was not yet finished), the armada was greeted with an outpouring of patriotic support and great fanfare as it paraded up the coast by seemingly the entire populaces of San Diego, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

By the time “the White Glory of the Navy” reached the North Coast on May 19, 1908, all of Humboldt County was awaiting its arrival. For months the newspapers had chronicled its progress with almost daily reports, and as “Fleet day” neared, the papers were filled with announcements and advertisements for “Greet the Fleet” excursions and special sales of “stylish linen suits, sailor hats, and parasols” for the ladies who are “going to see the Fleet.”

Plans to welcome the “big fleet and its gallant crew” included special chartered excursions and parties and an announcement that “all Humboldt will enjoy a general holiday, and do homage to the great ironclad fleet.” The Naval Militia prepared to fire a 13-gun salute; the Hammond Lumber Company chartered the steamer Ravalli for its club members; and the Pacific Lumber Company announced that the plant at Scotia would be closed and the employees would have the “opportunity to see the passing vessels.”

It was a holiday for just about everyone but “the members of the police force.” Thousands turned out along the North Coast that rainy Tuesday morning to greet the fleet. The experience and feelings of many of them were articulated by the Humboldt Times writer Mrs. CM. Shields in a May 20, 1908, cover story:

We were not a moment too soon, for those ahead had scarcely reached the summit [Humboldt Hill on the Buhne Point] when the cry arose, “They are coming! I see the smoke!” Sure enough, a tiny dark thread of smoke was discerned amid the wavering layers of fog and haze, now visible and then lost to sight. The fleet seemed to be rounding False Cape and it was some time before the several ships could be separated.

…At times the clouds would lower and obscure the sight, then arise again to show them nearer and more beautiful than before.

One by one we counted the ships as they swept closer inshore, and found to our joy that not one noble ship was missing. Sixteen battleships in stately array, keeping an even distance apart, moving sure and strong without a roll or dip, the white foam falling in cascades from the prows, passing before us in invincible array, the energized force and power of a great nation, aroused emotions that lie too deep for words….

At the moment when they seemed to be directly opposite us, and almost motionless, the clouds broke and the sun shone a Humboldt benediction on the white glory of our noble fleet; and as the bright rays drove the dark clouds and mist seaward, it seemed a beautiful comparison of the ease with which those powerful battleships could drive back from us the dark clouds of danger….

We watched the fleet as it stood off the bar and performed its maneuvers, forming in squadrons of four and making its pretty acknowledgement of courtesy, and then steaming swiftly off to sea. It quickly sailed out of our sight and we descended the hill feeling that we had seen the greatest sight of the times and one that we would not forget in a lifetime.

The joy of the occasion was marred by a local tragedy: In southern Humboldt hundreds of people from Ferndale, Grizzly Bluff, and Centerville had gathered in the early morning at the Centerville beach to greet and salute “the greatest fleet of fighting ships ever assembled under our flag,” and a group of them “acting on the impulse of the occasion” had brought out an old cannon and with a “booming roar hurled its fraternal greeting to its great brothers of war.” After six shots had been fired, it was suggested that a salute of greater volume be fired. When Ike Davis, a young Ferndale man, fired the heavily loaded cannon, the cannon exploded, killing him and seriously injuring several spectators.

This group of fleet-greeters were photographed as they waited at the Trinidad station for the train home. Photo by J.B. Meiser, via the Humboldt Historian.

Some of the largest crowds gathered at Trinidad because it was thought it would afford one of the best views of the fleet. Although the weather did not cooperate, the drama and emotional impact of the Great White Fleet was not lost on those who greeted it there — and in the Oregon and Washington ports that were next on the great voyage.

After its patriotic reception in Puget Sound, the fleet returned to San Francisco in early June 1908, passing by the North Coast out to sea without fanfare. On the seventh of July the fleet set sail from San Francisco for Hawaii, then south to Samoa and Figi, further south to Auckland, New Zealand, and on to Sidney and Melbourne, Australia.

After leaving Australia, the fleet sailed to the Philippines, which Spain had ceded to the United States under the 1898 Treaty of Paris.

Leaving Manila, the Great White Fleet encountered the worst typhoon to hit the China Seas in 40 years, with winds more than a hundred miles an hour.

The fleet’s arrival in the port of Yokohama was storm battered but magnificent. President Roosevelt had instructed his admirals to “choose only those on which you can absolutely depend. There must be no suspicion of insolence or rudeness” while on liberty in Japan. The Japanese policemen and soldiers were instructed by their government to salute Americans in uniform: thousands of Japanese children had been taught to say “welcome”: and tens of thousands of red, white, and blue lanterns had been hung.

The 3,000 American sailors permitted ashore under the watchful eye of the shore patrol behaved themselves, while the Japanese served soft drinks, paper parasols, and rickshaw rides — free. It is interesting to note that the Navy Shore Patrol was created on the world cruise of the Great White Fleet.

Upon leaving the Paciflc, the fleet sailed to Ceylon and Port Said through the Suez Canal — “the big ditch” — and the Mediterranean, splitting into four divisions to call on the ports of Beruit, Smyrna, Athens, Naples, Marseilles, and Tangier. Finally, the ships rendezvoused in Gibraltar for the straight-line non-stop cruise across the Atlantic. Arriving in its home port of Hampton Roads on February 22, 1909, the naval column, seven miles long, passed in review past the Mayflower with President Roosevelt looking on in pride, while thousands of citizens cheered as each battlewagon flred a 21-gun salute. The 14,000 sailors — having traveled 46,000 miles, visited 26 countries, and flred 100,000 rounds of saluting powder (about 30 times the amount expended in the Spanish-American War) — were home after an adventure of a lifetime, each of them having taken part in Uncle Sam’s Greatest Show on Earth.

From the Humboldt Times, May 20, 1908:

Eurekans on Fleet Day

- How the people fared forth to see the “fighting peace preservers” as they passed this port

- Beaches and bluffs lined as far as the eye could see — the trip on the steamer Kilburn

By George F. Nellist

###

The Atlantic fleet, sixteen battleships and one tender, floated proudly past this port yesterday, and after a short maneuver, the beautifully arranged flotilla wheeled out to sea, and was soon lost to sight in the light haze hovering about the surface of the water.

By 6:30 o’clock in the morning, the passengers residents of Eureka were astir, and ” making ready to meet the much heralded fleet when it arrived off the entrance. In the early part of the morning, dozens of automobiles were to be seen scudding arrival out to Table Bluff, South Bay, and Trinidad. Two thousand people took the train to Trinidad. Other innumerable hosts took advantage of the launches plying across the bay, and journeyed to the sand dunes ofthe peninsula. Last but not least, were the 500 patriotic citizens, who braved the dangers of an attack of mal de mer, and embarked on the Kilbum, Ravalli, and Ranger for the purpose of crossing out over the bar to see the armada at first hand.

And Humboldt style, it rained. Nearly all during the entire forenoon the elements were turned wide open, and IT RAINED.

Despite this inauspicious state of the weather, the optimistic patriots were in the best of humor, and awaited the first appearance of the yellow-funneled war dogs with unabated zeal.

The Kilburn was the first of the excursion steamers to leave her dock. She had been preceded by the Naval Militia boys in their launch and cutter. Soon after the departure ofthe Kilburn, the Ravalli followed, and close to her was the tug Ranger. In the passage down the harbor, every saw mill on the shore roared out with a whistled salute, being in every instance answered by the passing steamers.

Before the entrance was reached, people could be discerned up and down the beach as far as eye could reach. The abandoned trestle work of the old jetty undertaking was the place selected by many as a position from which to witness the passage of the ironclads.

The Kilburn, in the lead, continued on her way over the bar, until a position in close proximity to the stranded Corona was reached, when on account of the ugliness of the bar, the mud hook was cast over the side and the vessel anchored. The Ravalli followed the lead of the Kilburn, and hove to some three hundred yards to the rear of the leading steamer.

###

The story above was originally printed in the September-October 1990 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE