Skiers at Horse Mountain Lodge. Photo courtesy Bo Riewerts. All photos via the Humboldt Historian.

Skiing is not a sport that most people connect with Humboldt County, yet Horse Mountain, located in the present Six Rivers National Forest, played host to a bevy of snow-loving Humboldters for many years — from the late 1930s to the early 1980s. Although the golden era of Horse Mountain downhill skiing has passed with the consistently abundant snows of yesteryear, the people who were there during its heyday remember it with great fondness. (Snowshoers and Nordic skiers still enjoy Horse Mountain.)

The name most closely associated with Horse Mountain skiing is that of Dr. Jack Walsh. Dr. Walsh, together with his wife Mary and their children, took over the Humboldt Ski Cub operations at the top of Horse Mountain from about 1962 to the early 1980s.

Before we turn to the celebrated Walsh era, however, let us look at the earlier years, when an assortment of small skiing enterprises, with various types of rope tows, could be found on the mountain, including those set up by the Humboldt Ski Club, Bill Hilfiker and friends, and students at Humboldt State.

The lodge and skiers at New Prairie. 1955-56. Photo courtesy Ralph Kraus.

The Early Skiing Years

The Humboldt Ski Club was established as a non-profit organization in 1937 by Finn Jackson and Reggie Macro, among others. In 1948 they began skiing at New Prairie. They built a lodge at New Prairie approximately two miles south of Berry Summit, and had two rope tows running about a half-mile hike over the hill from Titlow Hill Road.

Upon his return from the Korean War, Bill Hilfiker headed up to New Prairie to try skiing again:

I had a pair of long, old Army surplus skis with bear trap bindings that would hold any old boot to the ski and never let go. My skis weren’t very good for turning, and neither was I. My Chesapeake Retriever and I took off down the hill — I could have gone faster if the hill were steeper, but I would have made a bigger hole when I fell. I grabbed the towrope, and up the hill my dog and I would go. After my second trip up the tow, I was informed by the Humboldt Ski Club that uncontrolled skiing and dogs weren’t allowed on their slope.

Before the war, Hilfiker had skied on Horse Mountain with his Boy Scout Explorer Post #180. They’d even begun to build a cabin on an abandoned mining claim near the summit. Now, with his dog and himself disinvited from the Humboldt Ski Club slope, Hilfiker got together with Fred, Willy and Nick Grediagin to build their own ski tow on the top of the mountain near their cabin. Bill Hilfiker’s father gave them a V8 engine and five-speed transmission in need of repair, and someone else came up with a free one- inch diameter towrope — a fishing boat reject. With these rudiments, they began improvising. Finally, they were able to fire up the tow, but their rope proved insufficient. Unwilling to wait for a special order towrope, they cadged one from the amenable folks at the Humboldt Ski Club.

In fifth gear, their tow was running at 25 mph. Bill describes the experience:

If you had enough nerve to get on the rope, you got to the top of the tow faster than you could ski down. Some girls had a problem getting on the tow, but that was no problem. We would straddle her skis with ours, put our arms around her and honey hug her up the hill. It was great fun. If she had a boyfriend too wimpy to get on the tow, the heck with him. We had his girl and he could walk.

The Hilfiker and friends’ tow was typical of early Horse Mountain skiing, where conditions were primitive and skiers had to make an effort to enjoy their sport. As Bill recalls:

We had a ski area and didn’t know how to ski, so we had to learn. We called the snow Horse Mountain powder, or HMP. It is a soft, heavy, wet snow that the skis sink into, making turning difficult. The best way we found to ski HMP was to keep up a good head of steam, keep our weight back on the skis and power though. It’s not pretty, but it works.

There were other independent ski operations and lodges in the area. Eddie Enquist built Enquist Lodge in the 1940s. It was located one to one-and-a-half miles south of the repeater towers. Ralph Kraus remembers it as a sizable building with guest rooms and a front room with a huge fireplace. After it was abandoned, Ralph and some of his friends used to camp in the lodge. One morning, someone woke up to find a rat sitting on his chest, which undoubtedly added to the excitement of “A Night on Horse Mountain.”

During his time as a Humboldt State College student, Ralph Kraus was instrumental in reviving their ski club. The college had its own lodge, about two miles up the road from Highway 299. They operated a portable ski tow with a five horsepower Briggs & Stratton engine, and spent more time repairing it than using it.

Another early skier (about 1951-52) was Mel “Pinkie” Pinkham, who owned City Garbage Company and the Humboldt Motor Stage. He would drive his Jeep to a prairie right after the first cattle guard, take off a rear tire and run a rope tow from the wheel on the tire rim.

Even at that time, during the 1940s and 50s, skiers were aware of the changing climate. Each winter the snow line receded up the mountain, and the Humboldt Ski Club slope at New Prairie was in trouble, although there were several seasons of heavy snow in the fifties, after the lodge was built.

Bill Hilfiker and his friends had invited the Humboldt Ski Club to ski at their area at the summit, but not many of them chose to do so at first because of the difficult road and the primitive conditions. Then the county stepped in to help. Bill recalls:

Global warming caught up with us and New Prairie lost its snow. The County began to plow the snow off the road to the top of Horse Mountain, and in 1958 the Humboldt Ski Club joined us. We were glad to have them — it wasn’t as much fun to ski by ourselves. The ski club installed two additional tows on the ridge for intermediate and beginner skiers.

Ralph Kraus and Al Braud were physical science teachers at Eureka Junior High, and they began the EJH Ski Club. “It went over like gangbusters,” Ralph said. He was able to drive a bus, so they would take 20-25 kids to New Prairie, then later to the top of the mountain. Their students were dedicated skiers. They had to be: before they could ski, they had to hike two miles from Berry Summit with their gear and lunches. Eventually the road was improved enough that they could take a bus all the way in.

The kids had fund-raising events to pay their way, usually movies at lunchtime for 10 cents a ticket. Ralph said, “Thanks to the generosity of the Humboldt Ski Club and later, Jack Walsh, we were able to take the junior high and senior high ski clubs, and ski at greatly reduced rope tow lift ticket rates.”

Ski Patrollers Ralph Kraus, left, and possibly Finn Jackson with sign: “Stay to left at bottom. Avoid ice. Dangerous.” Photo courtesy Jack Walsh.

The Ski Patrol

In a fast-paced sport like skiing, accidents happen, and the local Ski Patrol was there to help out from the time of the New Prairie era. Members included Ralph Kraus, Ray Jerland, Frank Kutil, Weldon Benzinger, Alan Battle, Dale McGrew, Jack Walsh, Wendy Cole, Brice Papini, Ron Wilson, Paul Jerland, Heidi and Edith Kraus, Roger Tinkey, Martin Lenz and many others. They had their own A-frame cabin and patrolled Horse Mountain every operating day. They were qualified to work any ski area in the West, and some of the members also worked at Ashland, Bachelor, Shasta, and Lassen.

Winter weather could be treacherous and fast changing, and people sometimes got lost. The Ski Patrol assisted the Sheriff ’s Department during snow searches. One year, a group of young people skied out on the wrong side of the mountain. When they didn’t come home, the Sheriff ’s Department was called, and the Ski Patrol went looking for them, eventually finding them at New Prairie, where the young folks had taken shelter in a sauna and were safe.

Packing injured skiers out of the ski area required a wooden, eight-foot rescue sled called a Tod-Boggan with a Stokes litter mounted on top. They also used Cascade sleds, which were the latest fiberglass rescue sleds available. Skiing the sled downhill was easy, but to bring people back up the hill, rescuers had to stand between the front handles and strap the sled to their bodies so they’d have their hands free to hold the grippers.

Accident reports show facial abrasions, lacerations, bruises and dislocations. One succinct description was provided by an injured boy, “I hit a tree and fell and broke my arm.” All told, injuries were few and far between, even celebrated. Jack Walsh has a card onto which an injured skier had taped five stitches after their removal, dated 1968. It was given to members of the Ski Patrol and says, “For you (you lucky bums).”

Jack & Mary Walsh and their van, March 1980. The Walshes raised 10 kids and enjoyed a “the more the merrier” attitude when it came to friends and the neighborhood children. Photo: Jack Walsh.

Hiouska! The Walsh Era

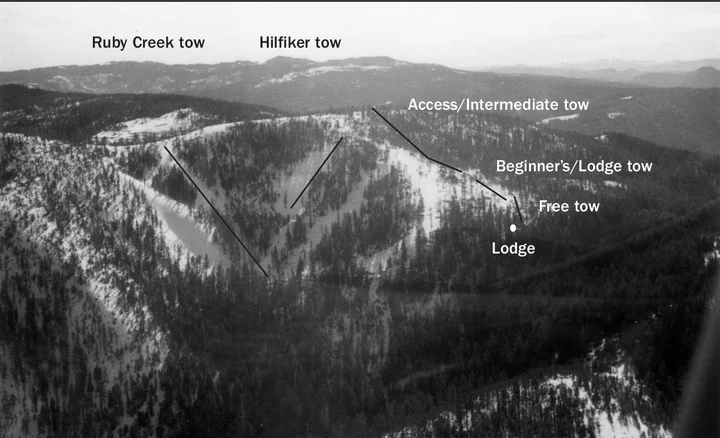

Many young skiers got their start because of Jack and Mary Walsh. In 1962, Jack took over the permits and began running the ski area with the help of Mary and their large family. Most of the land was cleared, but Jack opened up the Ruby Creek area, for a total of six rope tows:

- The Beginner’s (or Lodge) tow ran from the lodge about 600 feet uphill.

- A free tow, powered by a small gas engine, operated from the lodge up the lower portion of the west side slope. It was about a hundred feet long.

- The Intermediate tow ran from just above the top of the Lodge tow to the top of Horse Mountain. It was built by the Humboldt Ski Club. Ultimately it was replaced by an electric motor drive in a permanent building that sat at the north edge of the parking lot at Horse Mountain summit.

- Hilfiker’s tow, the advanced rope tow, serviced a steep slope on the east side of the ridge and ski run between the parking lot and lodge to the north.

- The Ruby Creek tow was pioneered entirely by Dr. Walsh. The towline ran up the hill pretty much parallel to the upper reach of Ruby Creek.

There were several structures used by the skiers. The main lodge was built in the 1960s by Gary Wing and general contractor Gerald Carrico. The ticket booth and the snack shack were next to the lodge at the bottom of the Lodge Tow. The Ski Patrol had their own A-frame on the east side of the Lodge tow ski hill, about one-third of the way from the bottom of the mountain. Three-people teams ran the main tows, switching every hour (and skiing for free in return). Cedar Creek Lodge was built by Bill Hilfiker, the Grediagin brothers, Art Pierce, Werner Martin and Don Stone. Ralph Kraus described it as “a fine cabin with a large stone fireplace.”

Newspaper articles from that time report ski school programs and other ski instruction opportunities, and the results of races, as well as photos of the skiers.

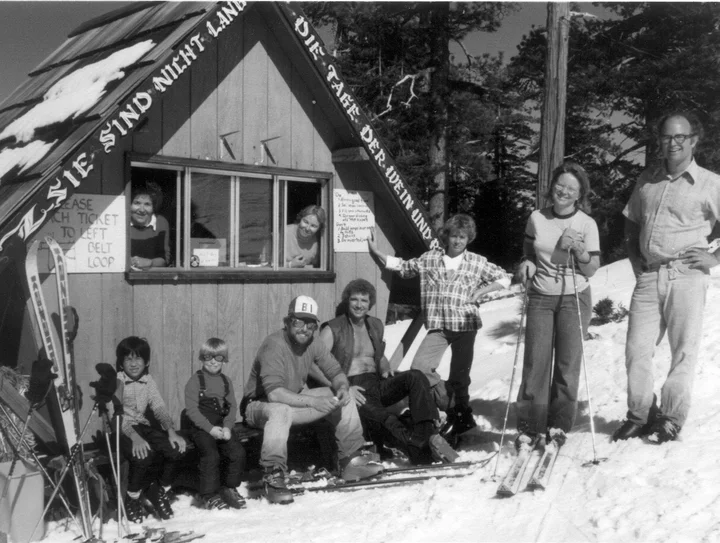

Snack Shack, March 1967. In the windows: Mary Walsh and Patti Wing. Below from left: Jess & Kenny Bareilles, Gary Wing, James Sutton, Jack Bareilles, Linda Bareilles, and Ken B. Bareilles. Photo courtesy Jack Walsh.

The Walshes had a “the more the merrier” attitude and allowed kids from their neighborhood to pile into their Ford Econoline van. Several people expressed awe at Mary Walsh’s ability to good-naturedly care for and feed their own ten children (at one point, three of them were in diapers), as well as their friends. She also ran the ticket shack for the rope tow, selling 200-250 tickets on a good day. “She was the backbone behind this whole thing,” her daughter, Liz Walsh Day said.

Bo Riewerts remembers trips to the mountain with the Walshes:

Jack regularly included neighborhood children along with all of his family on trips to Horse Mountain. Although the Walsh van was typically packed full, his attitude was that there was always room for more children in the back of the van. We piled in from the back and sat on top of the skis. One needed to remember to use the bathroom before the van left, since there would be no stopping until we reached Horse Mountain. Those who forgot that detail were told to use the plastic bucket that always accompanied all Walsh family car outings. Jack took his medical expertise along on every journey; after all it was just taking a pee. If you ever got hurt on an outing to Horse Mountain, Jack would quickly assess the injury and likely encourage us to just move on down the slopes.

This family-oriented environment prevailed at the ski area. A brochure from 1965 asserts, “A friendly atmosphere prevails on the slopes which serves skiers of all abilities, from first time beginners to seasoned pros.”

The infamous Ruby Creek tow engineered by Jack Walsh is remembered by all. It was a quarter of a mile long, the longest and steepest tow in the United States. According to Ralph Kraus, it was the most exciting thing about Horse Mountain: it was rugged and it ran fast.

Rob Dunaway remembers:

The lodge hill was not too steep, so riding the rope tow up that hill was not too bad. Many regulars had the metal gripper device that clamped on the rope tow like a pair of pliers and made it easier. Ruby Creek was steep and long. It was difficult to make it to the top without a gripper. I remember my arms and hands completely going numb every time up, always afraid of falling and tumbling into a ravine. If your hands cramped, you would lose your grip on the rope and it would speed through your hands, literally burning away your leather glove palms in a few seconds. You had to hang on at all costs. Gloves wore out very fast at Horse Mountain.

Horse Mountain was not the easiest place to ski and certainly not the easiest place to learn. This was an era not too far removed from leather ski boots and all wooden skis. Also, the weather pattern back in the late 60s and early 70s brought a lot more rain and snow to Humboldt County than today’s weather pattern. The snow at Horse Mountain was usually wet, heavy with Pacific storm moisture, not the light, fluffy snow you find in higher altitudes.

These difficulties didn’t stop the skiers, although there were some visitors who didn’t appreciate the challenges offered.

Rope tows were inspected annually by the state (the Forest Service also checked the area for safety compliance). Ralph Kraus tells the story of a state inspector who made it to the bottom of the Ruby Creek area, then asked, “How do I get out of here?” Jack stopped the rope tow, put a gripper on the rope for the inspector and told him to hold on, promising that they’d start the tow gradually. The inspector, unaware of Ruby Creek’s reputation, held the gripper with one hand and his cigarette with the other.

Jack yelled, “Toot toot!” which was the signal to start. Far from starting the tow gradually, the operator popped the clutch, sending the inspector flying one way and his cigarette the other. Jack got him up and they tried again, with no better results.

Perhaps to take the inspector’s mind off his woes, Jack pointed out that the tail wheel for the tow was horizontal when it was supposed to be vertical and said he’d fix it immediately. The inspector said, “I don’t give a damn what you do with the tail wheel — just get me out of here!”

Safety precautions were taken with the tows. The Lodge tow had a safety gate, a rope that shut down the tow if someone’s hair or scarf got caught. The rope ran through the “splatter board,” a thin sheet of plywood that prevented the skier from getting caught in the mechanism.

The late, great Jackie Walsh mid-air. 1976. Photo courtesy Jack Walsh, via the Humboldt Historian.

Dave Murray shares an early experience:

The Horse Mountain memory indelibly burned in my mind comes from the very first run I made down to the base while in Eureka High School. Through the help of my good neighborhood buddy, Jim Otto, I was given an opportunity to join the fun at “Horse” one day. Having geared up, I took a cautious line down the side of the slope in order to be less of a hazard to myself, and other, more proficient skiers. Suddenly, off to my right, came a percussive “whump!” and a light shower of snow. I looked up in time to see the (late, great, tremendously athletic) Jackie Walsh Jr. fly past over me. Jackie, as cool as our surroundings, looked down at me and casually said “Hi, Dave.” Landing in perfect balance, he carved a quick turn, and was soon off in the distance. While I aspired to be “that guy,” I was, like most people, never on par with Jackie. Nonetheless, my days at Horse Mountain yielded the kind of fun, friendships and recollections that never fade.

Most skiers only stayed for the day, but sometimes people did spend the night. Weldon Benzinger strung lights along the trees (electricity had come to the mountain by about 1966, also allowing them to install electric tows). Butch Mathews remembers watching the first Super Bowl during a Horse Mountain sleepover, on a television that Weldon’s dad provided.

Tom Quigley shares a racing anecdote:

Steve Herzig, a very experienced agent of near-death experiences on the Ruby Creek ski run, had drawn my name as his challenger for the side-by- side slalom race one sunny afternoon. I had only skied 15 days at most, and I was determined to be focused and careful. A fall could mean a slide all the way to the bottom and into the creek. The flag dropped and we two 17-year-olds began the duel; Steve in his flash and screams, me wearing my black Rupp Skimobile jump suit, trying to capture the same frenetic energy that was propelling Steve. The suit, ugly as it was, gave me courage and confidence, due to its super powers. Alas, it would not have been enough, had the wild Steve-O stayed on his feet. Crashing and sliding across my path, Steve solidified a moral victory for me, which I obviously still remember 43 years later. By the way, Steve did not make the creek, and I did not give him a rematch. Hiouska!

“Hiouska” was a word posted above the Ruby Creek tow run by Dr. Walsh. Although no one seems to know the origin of the word, to Horse Mountain denizens, it meant, “Go for it!” It is still the motto of the Horse Mountain Grippers, a group of skiers who reconnected about twenty years ago and meet several times a year to ski and bike together.

About 1975, Jack Walsh decided to set up a Hedko snowmaking machine. A large air compressor fed water to it and Jack paid people to spend the night and run the machine. One night, the crew wasn’t watching carefully and the pump ran out of oil, sending an icy spray of water over the slope. The result was a patch of ice approximately twenty yards wide and five feet deep, which took a month to melt. Between the cost of the machine and having to pay a crew, Jack decided to sell it. Running Horse Mountain was a labor of love — financially, they usually broke even.

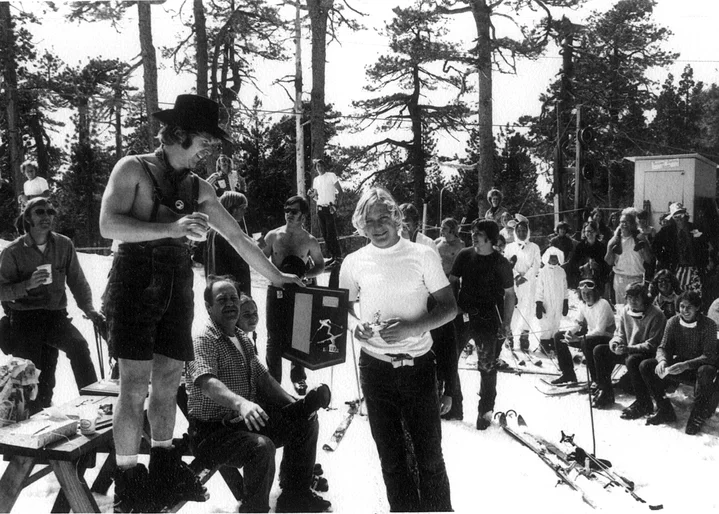

End-of-the-season Hot Dog, Beer, and Fashion Festival. In the foreground Danny Walsh in lederhosen hands a trophy to Jackie Walsh. To the right of Jackie, in the background, note Mary Walsh in her traditional bunny suit. Photo courtesy Jack Walsh.

At the end of every season, there was a day of celebration and fun: the Hot Dog, Beer, and Fashion Festival. Beer and hot dogs were provided, and skiing was free if you wore a costume. Photos published in the Times-Standard show laughing people wearing everything from lederhosen to a bunny costume (Mary Walsh). Winners of the costume “fashion parade” were decided by popular acclaim. Free hot dogs bubbled in a pot over an open fire.

There were also the races.The Alpine Combined Ski Race started with George Severson in 1948. The trophy was retired and given to Bill Hilfiker after he won it three times in a row.

Besides the Alpine Combined race, there was the Children’s ski race and the Prairie Run, but the race that people seem to remember best is the Beer race: skiers went through a series of gates, drinking a cup of beer at each gate, handed to them by gate keepers. Bill Hilfiker usually won that race, as well, and he may have inspired Ralph Kraus to create “a very clever Beer race trophy made from a funnel-headed wire figure on skis.”

Butch Mathews and Bo Riewerts were gatekeepers when they were about fourteen years old, and decided to sample the beer in between racers. Unfortunately, they sampled a bit too much. According to Butch, he managed to lose the hot dogs he had eaten before they left the mountain, but they had to stop several times on the way down for Bo.

During the early 1980s, Gary Wing took over as ski instructor. He owned a ski shop in Eureka, and Ralph Kraus remembers him as being instrumental in keeping the rope tows and other equipment running, especially toward the end of the commercial operation. By that time, snow was becoming sparse, and with fewer skiers to pay for permits, insurance and other expenses, the Horse Mountain ski area had to shut down in the early 1980s.

Rob Dunaway reflects on his time at Horse Mountain:

Looking back, there was a bit of magic in any hard endeavor that bonded people together. Rite of passage, mutual misery, whatever. Skiing at Horse Mountain was not for the timid. But, oftentimes, you would know half of the people on the mountain. What could be better than skiing with fifty of your friends and family? It was a unique place and run by a unique family, the Walshes. It was definitely a labor of love, not profit. Walshes would be everywhere, a daughter selling and taking tickets, a son firing up the rope tows, another opening the lodge. “Lodge” is a bit of a misnomer; it was a small cabin but we all called it the lodge. We had people that were Ski Patrol members — who can forget Weldon Benzinger, one of our high school teachers and a friend to all of the Grippers today, wedeln down the hill? For such a primitive ski area, there were a lot of very good skiers.

Kirk Cesaretti sums up his time at Horse Mountain:

My first exposure to Horse Mountain was in 1966, I was four years old and it was raining. Snow and rain are a miserable combination and to this day I remember Horse Mountain as a place with a certain amount of misery and magic. Growing up in Humboldt County does not typically lend itself to winter sports. Horse Mountain met a specific Humboldt County need. It allowed for snow day excursions and for local kids to learn how to ski who otherwise might never have had that opportunity.

The magic of Horse Mountain by far surpassed its ability to make you suffer. Perhaps, part of the magic was that you succeeded while enduring the suffering. Coming into the lodge and getting warm by the fire. Sleeping overnight in an igloo. Spending all day ski jumping your own hand-shoveled jump and perfecting tricks made young egos thrive. The camaraderie of the mountain was part of its charm. You knew most of the people on the mountain. My next-door neighbor, Ray Jerland, was a ski patrolman. My junior high science teacher, Ralph Kraus, was also a ski patrolman. My high school physics teacher, Weldon Benzinger, was a ski patrolman and also our High School Ski Club advisor. Horse Mountain connected people.

That last sentence is perhaps the heart of the Horse Mountain experience. It wasn’t just skiing, although they loved to ski. It was family and friends; it was Swiss native Hans Giovanoli yodeling as he skied; it was the first time you conquered the Ruby Creek tow, and how, once you learned “mashed potato” skiing on the Ruby Creek slope, you could ski anywhere. It was about lifelong habits of physical fitness inspired by Dr. Walsh. It was about building friendship and community. For many of the people who were children at that time, it was learning the quality of hiouska, the determination that enabled them to go for what they wanted in life. Liz Walsh Day and Heidi Kraus O’Neil went on to ski competitively, and Liz still works as a ski instructor. Others chose hiouska-fueled professional careers. Bo Riewerts and Peter Welty became physicians, inspired by their mentor, Dr. Walsh. Bo says, “We owe much of that ongoing fun and success to Jack Walsh and his entire family.”

The ski area may be gone, but the legacy of Horse Mountain continues.

###

The story above was originally printed in the Summer 2016 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

###

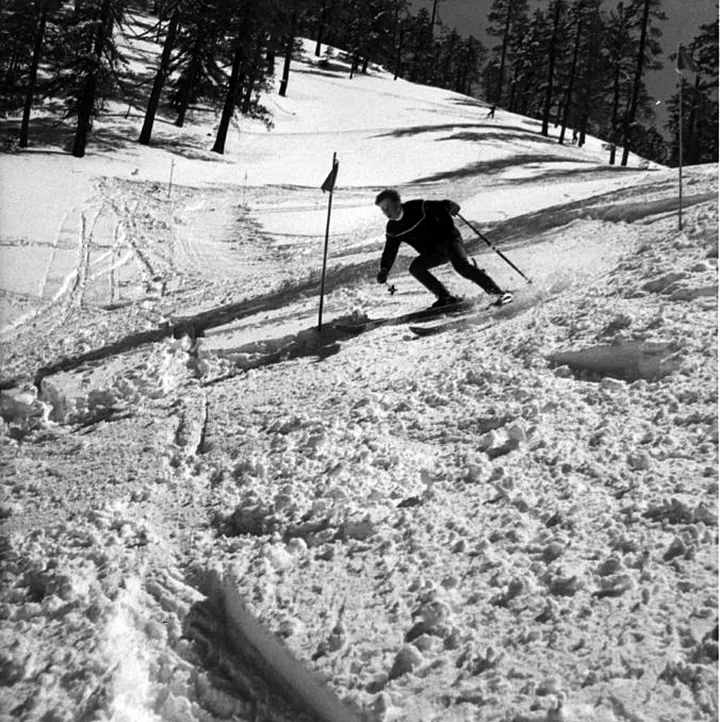

Sumner Dennon III, on the slalom course.

Larry Peterson on the downhill race course.

CLICK TO MANAGE