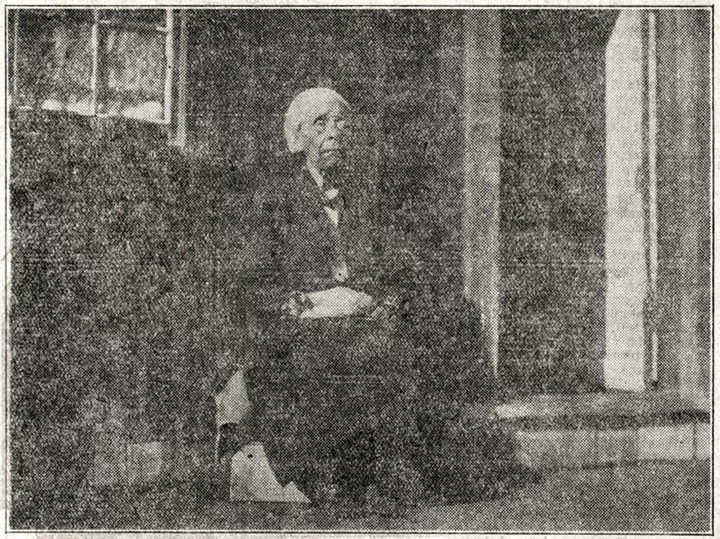

Annie Sam. Photo via the Humboldt Times.

This story will have no great, if any, impact on the history of Humboldt County for it is a simple one. Yet for 50 years it has haunted my memory, and to the best of my knowledge it never has been told until now.

Besides, back there was a lovely and even then ancient Indian lady who lived a lonely and almost incredibly heroic life and thus deserves more, if only this bit more, than the nameless pauper’s grave to which she must have been consigned.

It is the story of Blind Annie. What her true name may have been, or her age, none of us ever knew. She could have been 80 or she could have been 120. Her sculptured face, weathered by sun, wind and salt spray to a rich and beautiful mahogany, kept her secret, and it is probably true that she herself did not know the number of her years, Annie reputedly was one of the few survivors of the atrocity of Indian Island in Humboldt Bay — the Massacre of the Innocents — of 1860. This, though unprovable, is not improbable, since legend held that “a young girl” had escaped the wanton slaughter by means of throwing herself into the bay and drifting with the outgoing tide on a log, or other flotsam, to the sandy beach just north of the point where Elk River enters the bay south of Bucksport.

Since our encounter here occurred during the mid-1920s, Annie’s apparent age would come well within the span of years to make that a possibility.

She lived in a rude one-room cabin perhaps a dozen yards above the high tide line, and legend also held that she had built it herself. This, too, bears weight because the principal construction was of vertical log slabs much in the fashion of the older Indian homes along the Klamath and Trinity Rivers, I clearly remember the shallow-ridged roof, and how she could have managed that is part of the mystery, for Annie was a tiny woman. One could see daylight through it from the inside, in many places, yet when it rained not a single drop came through. There was no floor, and a small wood fire inside a circle of stones in the center kept her reasonably warm and served her for cooking during inclement weather. Otherwise, she cooked outside, within a similar circle of stones. She had few utensils, needed nearly none. That, then, sets the basic picture.

So, why did we not simply ask Annie if she truly was a survivor of the white mob’s massive brutality back there on Indian Island? We did, on several occasions. And in each case, the soft spoken lady became totally mute, the dim light in her eyes retreating into their darker depths. And she would speak no more that day. We soon stopped asking.

Now — who were “we,” of all the previous references herein? “We” were the members of Troop 20, Boy Scouts of America. The writer was a Second Class Scout in the Owl Patrol. We had “adopted” Annie. In the beginning she was what then was called a Troop Project. In a very brief time, Annie became a Love Project for each and all of us. The project was to keep her well supplied with firewood and kindling, which we garnered from up and down the beach, sawed and split, and stacked against the wall of the cabin within easy reach, with the kindling placed inside in a corner, out of the weather.

Annie soon come to know each of us individually, by passing her hands over our faces, our hair, asking its color and the color of our eyes, and measuring our heights against her own. One of her almost incredible accomplishments was that she came to identify each of us when we walked alone, past or near to her, by our footsteps — in the sand. For a long, long time she delighted in not telling us how she managed this, but she finally yielded. It was by sound, faint as it was.

“You no weigh same,” she grinned.

The ancient lady was self-sufficient so far as sea foods, then plentiful on the long, sloping shore, were concerned. She caught crabs simply by wading out in little more than ankle- deep water and feeling for them. These she cooked in a small galvanized wash tub, which she filled with salt bay water from a finely woven basket. She was adept with a fishing line, using tube worms and clam necks for bait.

Clams she dug with an instrument which she herself devised, and I have never since seen another like it. It was, basically, a tree limb about five feet long, with one short branch for her foot near the digging end. The blade she had fire-hardened, then flattened and polished with stones, so that it was as good as any shovel ever manufactured. Annie in fact spurned the “real” shovel and most other implements we brought her. The clams she cooked simply by placing them on the hot sand near the fire, the fish on stocks set at an angle over the coals. The eggs we brought her periodically she simply buried in the same hot sand.

A big treat for Annie, whenever we could get them in season, was fresh berries, domestic or wild, although she managed well with some nearby wild blackberries herself, , judging by feel when they were ripe.

Her bathing and what little laundry she had were done in the waters of the Elk River mouth, regardless of the weather. And then we grew older, and went our ways, and when I returned to Humboldt County many years later, all trace of Annie, and even of the old cabin, had vanished.

As I said, this story is no epic, but whoever the kind and lovable old lady may have been, she now shares a tiny niche in the history she shared and, to this degree, made.

Annie was far from blind. She was only sightless.

###

Ed. note: Annie’s sister, Jane Sam, told her story of surviving the the Indian Island massacre. Historian Jerry Rohde refers to this story in this article.

###

The story above was originally printed in the May-June 1976 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE