National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration release:

Demolition of Copco No. 1 Dam (Credit: Whitney Hassett/Swiftwater Films)

For the first time since 1918, an astonishing 420 miles of salmon habitat in the Klamath River watershed in California and Oregon will be fully connected by September. This results from the world’s largest dam removal effort, the Klamath River Renewal Project. The amount of habitat opened up on the Klamath is equivalent to the distance between Portland, Maine, and Philadelphia–a journey through seven states.

PacifiCorp, the previous owner, agreed to remove the aging dams after they determined removal would be less expensive than upgrading to current environmental standards. The dams had been used for power generation, not water storage. The Copco No. 2 Dam on the Klamath was removed last year. The deconstruction of the Iron Gate, Copco No. 1, and JC Boyle dams is underway and running ahead of schedule.

“I think in September, we may have some Chinook salmon and steelhead moseying upstream and checking things out for the first time in over 60 years,” says Bob Pagliuco, NOAA marine habitat resource specialist. “Based on what I’ve seen and what I know these fish can do, I think they will start occupying these habitats immediately. There won’t be any great numbers at first, but within several generations—10 to 15 years—new populations will be established.”

There’s more good news for Klamath salmon and steelhead. NOAA’s Office of Habitat Conservation recommends an $18 million award to the Yurok Tribe to restore and reconnect cold-water tributaries that will be open to migratory fish after dam removal. Another roughly $1.9 million award is recommended to the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife to begin evaluating options for improving fish passage at Keno Dam. The Keno Dam sits upstream of the dams currently being removed. Nearly 350 miles of additional salmon habitat lie upstream. Both awards are funded through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act.

“The Yurok people are extremely happy to be witnessing the beginning of the Klamath River’s rebirth,” says Yurok Tribe Fisheries Department Director Barry McCovey. “The dams caused a tremendous amount of damage to the Klamath over the last century. Through the decommissioning project and holistic restoration, we are confident that we will see the Klamath’s salmon, steelhead, and Pacific lamprey runs recover.”

A River Reborn

The Klamath River once produced the third-largest run of salmon in the lower 48 states. It was the lifeblood of tribes throughout the region and supported important commercial and recreational fisheries. However, major dam construction between 1918 and 1966 and other development cut off the upstream pathway for migrating salmon. Tribes and other community members who depended on salmon fisheries lost this critical cultural and subsistence resource.

In 2002, an estimated 30,000–70,000 fish perished in the Klamath River below the dams, partially due to low flows being released from the Iron Gate Dam. Following this event, the Yurok Tribe launched an investigation and, together with other tribes, called for removal of the dams. Since then, NOAA and other federal, state, and local agencies as well as nonprofits and other groups have joined the effort. The Klamath River Renewal Corporation took over ownership of four dams from PacifiCorp, and is overseeing the removal process.

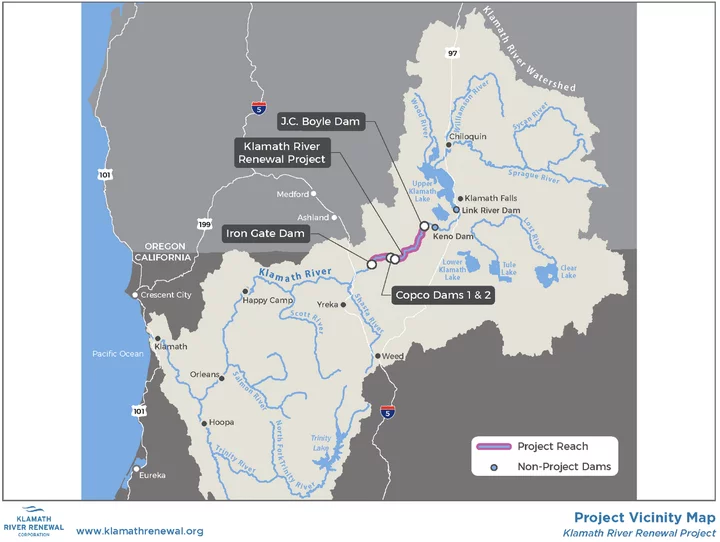

Map of the Klamath River watershed showing the four dams being removed as part of the Klamath Renewal Project as well the upstream Keno and Link River dams | Klamath River Renewal Corporation

In April, NOAA scientists, restoration specialists, and the head of NOAA Fisheries, Janet Coit, gathered on a slope above the Klamath River to watch it being reborn. Over the winter, crews had breached three of the remaining major dams blocking the river’s natural flow, draining the reservoirs behind them. The river found its historical channel for the first time in more than a century, a crucial step in preparing the habitat for the return of salmon.

“Many of our colleagues have spent more than 20 years working towards this moment,” says NOAA Fish Biologist Shari Witmore. “Watching the recovery and how quickly it’s happening has been impressive and emotional for us all.”

In the long term, dam removal will significantly improve water quality in the Klamath. “Algae problems in the reservoirs behind the dams were so bad that the water was dangerous for contact during the summertime, meaning it was not safe for you and your dog to swim in and not drinkable,” says Fluvial Geomorphologist Brian Cluer. “Taking these large reservoirs out gives the river water a chance to aerate, increasing oxygen levels and reducing algae production.” It will also reduce water temperatures and the risk of salmon-killing disease outbreaks.

Plants sprouting from the reservoir footprint on the Klamath (Credit: Tommy Williams/NOAA)

Helping Salmon Adapt to Climate Change

Reconnecting the river will help salmon and steelhead populations survive a warming climate and disasters like forest fires and droughts. Migrating adults will be able to reach spawning grounds in tributaries with cold-water springs, increasing the survival rate of juveniles. With access to more habitat, fish can distribute across the landscape within the Klamath Basin. “If a forest fire impacts a specific river reach or tributary, individuals or populations elsewhere in the Basin can still support fish from that same cohort, year class, or life stage,” says NOAA Research Fisheries Biologist Tommy Williams. “Fish from other tributaries or mainstem areas are available to sustain the Basin’s populations as a whole.”

The window for migration will also widen. “There are probably going to be fish moving back and forth 365 days a year,” says Williams. “This expanded migration period helps the population because the freshwater and marine environment are dynamic and variable. If conditions are less than favorable at a specific time or location, fish migrating throughout an expanded migration window are more likely to find favorable conditions.”

Providing access to what historically was a more complex, dynamic ecosystem strengthens their ability to adapt to challenges. “When you simplify the habitat as we did with the dams, salmon can’t express the full range of their life-history diversity,” says Williams. “The Klamath watershed is very prone to disturbance. The environment throughout the historical range of Pacific salmon and steelhead is very dynamic. We have fires, floods, earthquakes, you name it. These fish not only deal with it well, it’s required for their survival by allowing the expression of the full range of their diversity. It challenges them. Through this, they develop this capacity to deal with environmental changes.”

Painting of salmon migrating up the Klamath by Mt. Adams Institute Veteran Intern Evan Daley. The Mt. Adams Institute Veteran Intern program is funded by NOAA.

The Return of Salmon

NOAA scientists expect small numbers of salmon will begin swimming upstream following the removal of dams this fall. But, it will take years before sizable populations return. Salmon and steelhead have 3- to 5-year life cycles, so fish born in the river won’t return for several years.

“For most of these species, it’s going to take four or five generations—12 to 25 years—before we see established populations upriver,” says Williams. “And that’s contingent on many other things like ocean conditions, droughts, and fires. A lesson from the Elwha River dam removals was that the response time varies among species and perhaps for populations in specific locations within a large river basin. In the Klamath Basin we will very likely also observe differences among species and perhaps among populations within species in the time it takes to establish populations.”

However, repopulation may occur more quickly than the 12–25 years it could take for these species to reestablish in the Klamath basin. “We’re 10 years past the removal of major dams on Elwha River in Washington, which was blocked for more than 100 years,” says Williams. “It’s now seeing large numbers of fall Chinook salmon. That’s two and a half generations. This gives us confidence in what these fish can do.”

Models predict that as many as 80 percent more Chinook salmon could return to the Klamath basin within 30 years–six to 10 fish generations. Ocean harvest could increase by as much as 46 percent.

The California and Oregon departments of fish and wildlife expect most fish populations will naturally repopulate the watershed. Stray salmon will lead the way. Salmon and steelhead typically return to the streams where they were born to reproduce. However, a growing body of evidence shows that both adult and juvenile fish occasionally stray from their natal habitat to explore new areas. This type of dispersal is well suited for the dynamic environment where salmon are found.

Salmon migrating upstream (Credit: Mid-Klamath Watershed Council)

The straying of some fish helps a population’s genetic legacy outlast disturbances in the stream where they were born. “If you have a few individuals in a population who don’t return home and something happens—Mt. St. Helens erupts and fills the Toutle River with large flows of sediment, killing the fish there—the strays live on,” says Williams. “It’s more or less genetically and demographically beneficial for fish to have this capacity, so if the population gets knocked down, its legacy has a chance to return. In addition, dispersal of fish from other watersheds will find their way into streams and rivers like what happened in the Toutle River.”

Williams expects that after the dam removals, a few fish will disperse upstream and find historical spawning areas. Some of their offspring will return to those streams, and others will find different streams nearby. Slowly, populations will expand across the landscape.

NOAA’s state and tribal partners will conduct extensive monitoring to understand how fish use and repopulate the newly opened habitat. Partners are planning to monitor the effectiveness of the dam removal project using a sonar camera and in-river sampling. This will determine the number and species of fish that are passing by the former Iron Gate Dam site. The project team will also radio tag a subset of these fish and track their journey as they reoccupy new habitat. NOAA will use this information to evaluate the effectiveness of restoration investments, and manage commercial, sport, and tribal fisheries.

Keno Dam on the Klamath River in Oregon located at river mile 236.4. (Credit: Mark Hereford/ODFW)

What’s Next: Reservoir Reach and Fish Passage at Keno Dam

Once the dams come down, NOAA and its partners will begin restoring the Reservoir Reach. That’s the mainstem river and tributaries between the site of the Iron Gate Dam and Link River Dam. “Dam removal is a huge first step, but we’re not done yet,” says Pagliuco. “We need to continue to restore this area to give salmon the best chance to recover.”

In 2022, NOAA, Trout Unlimited, and the Pacific State’s Marine Fisheries Commission released a Reservoir Reach restoration plan that detailed 200 projects to improve salmon habitat. NOAA recently recommended $20 million in funding to address major priorities identified in the plan.

The Yurok Tribe will design and implement habitat restoration in several priority tributaries in the Upper Klamath Basin with an $18 million award. They will:

- Restore up to 140 acres of floodplain habitat

- Reopen 16 miles of stream habitat

- Construct 20 acres of instream habitat features such as logjams and spawning gravels

The Yurok Tribe and NOAA, in collaboration with other tribes and nonprofits, will identify high-priority sites through the planning and design process.

The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife is exploring fish passage options at Keno Dam with a recently recommended $1.9 million NOAA award. The Keno Dam sits between the soon-to-be removed JC Boyle Dam and Link River Dam, the most upstream dam on the river.

“The fish ladder on the Keno Dam was not designed to pass anadromous fish,” says Williams. “It was built after two downstream dams were in place when salmon were already blocked from migrating upstream.” When the three downstream dams come down this fall, migratory fish will finally be able to reach the Keno Dam. But, they might have difficulty finding the fish ladder or passing this structure that anadromous salmon and steelhead have never tested.”

Alternatives for fish passage range from building a salmon-friendly fish ladder to completing dam removal. Designs would need to both provide fish passage and retain irrigation and other functions for the surrounding community. Over the next 3 years, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and its partners will:

- Identify fish passage options in coordination with partners, tribes, and community members

- Study the feasibility of the most viable fish passage options

- Develop cost estimates

- Create a 30-percent engineering design for the chosen option

The Klamath Tribe’s ancestors subsisted on salmon for millennia before the dams were built. Tribe members will play a key role in developing and evaluating fish passage options.

Additional partners include:

- Shasta Indian Nation

- Modoc Nation

- Karuk Tribe

- Ridges to Riffles Indigenous Conservation Group

- Trout Unlimited

- Klamath Water Users Association

Together, this $20 million investment will be truly transformational. It will begin to reverse decades of habitat degradation, allow threatened salmon species to be resilient in the face of climate change, and restore tribal connections to their traditional food source.

CLICK TO MANAGE